As soon as you move east of the historic Shelby visitor center on U.S. 2, you encounter the landmarks that physically mark the region’s agricultural character. On the north side of the highway, immediately adjacent to the tracks are complexes of grain elevators. Here at Shelby there is a tall concrete group of elevators run by CHS–the appearance of concrete elevators always mark a town that has experienced economic growth in the second half of the twentieth century. Many of the smaller Hi-Line towns have the classic frame elevators of the homesteading era. Grain elevators thus become a physical barometer of a place’s economic prosperity and development.

On the south side of the highway in Shelby is the second crucial agricultural institution, the county fairgrounds and rodeo arena. Livestock is not only important to the economy but maybe even more important to the culture of the region. The Marias 4 County Fair, held the third week of July, is a regional gathering of no equal. Thousands attend, and they do so at a fairgrounds with an impressive collection of historic buildings.

In 1984, I noted this east side of Shelby as I left the town, but my eyes and camera were focused on the small railroad towns that I would next encounter, along with two important historic sites I wanted to document.

Whoop-Up Trail site, U.S. 2, 1984

The first was the Whoop-Up Trail remnant, a site first documented by state archaeologists in 1968 and among the handful of historic properties then identified in Toole County (another section of the trail near Kevin is listed in the National Register). In 1984 the location along the highway was well marked, with a series of stones marking the trail and encouraging visitors to go to the property edge and look into the Marias landscape where this historic route between Fort Benton and Fort Whoop-Up in Canada once passed.

In fact to the south of U.S. 2, a county road still crosses the Marias near the old trail crossing: it was a somber, beautiful place in 1984. In 2013, the Whoop-Up Trail site is still maintained, put the line of stones to mark the path has either been taken up or covered by growth.

In fact to the south of U.S. 2, a county road still crosses the Marias near the old trail crossing: it was a somber, beautiful place in 1984. In 2013, the Whoop-Up Trail site is still maintained, put the line of stones to mark the path has either been taken up or covered by growth.

Across the highway remains another key landmark of the Hi-Line and Central Montana region: a nuclear missile silo. These military bases are everywhere it seems, and sometimes in the most unlikely places. By 1984 I had become somewhat accustomed to their presence–coming from the South I had no idea of the role Montana played in our nation’s defense.

But the missile silo was a surprise: what I really was seeking was something on the Marias River–or Baker–Massacre, one of the most horrific events of Montana’s early territorial period. The site is east of Shelby and south of U.S. 2 on private ranch land–and the family has been excellent stewards of this place. No need for me to tred on such sacred ground, but there is a need to intepret that story, and to tell visitors and residents that here in this seemingly peaceful beautiful countryside a group of territorial citizens murdered Blackfeet women, children, and elderly in some sort of mindless bloody search for revenge. That story wasn’t told in 1984 but a long text marker does so now. It strikes the right message: that the massacre “profoundly impacted the Blackfeet people and is very much alive in tribal memory.” A small bouquet of flowers at the marker’s base in 2013 testifies to the truth of this simple memorial.

Dunkirk, the first of a trio of Toole County railroad villages east of Shelby, was too close to Shelby itself to ever maintain its own identity for long. Its Frontier Bar was long a worthy roadside stop for thirsty travelers. Outside of the Westermark Grain Corporation elevators, the bar was the only reason to even give Dunkirk a glance.

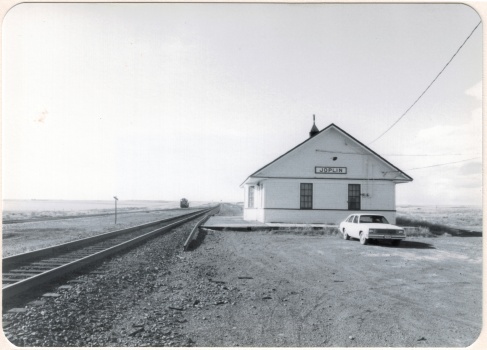

Devon is a plains country town on the Great Northern Railway that was the first “prairie ghost town” of the 1984 survey. Numerous false-front frame buildings from the 1910s and 1920s existed in 1984: 30 years later several of these were gone.

Devon streetscape, 1984

Devon, Montana, 1984

Devon grain elevator, 1984

Yet I must admit that Devon now had more to it than what I recalled from 1984. Certainly the old brick bank building had been abandoned, and the town community hall appeared shuttered, but the contemporary-styled Devon Lutheran Church spoke to persistence, even after decades of economic change. The grain elevators that were prominent in 1984 also had persisted, and stood as three sentinels on the plains.

Galata, established in 1901, is another Great Northern Railway stop, with its corridor landscape speaking to its isolation and agricultural dependence. It is a T-town plan town, where the main street forms the stem of the T while the railroad tracks form the top of the T.

In the latter half of the 20th century, Galata had actually reached beyond its T-town plan and out to the highway. Its Motel Galata is a classic piece of roadside architecture, and its huge highway sign of a Montana frontiersman with cowboy hat waving his car keys beckoning travelers to stop.

Galata also has kept its post office–a classic 1960s standardized design. But the real key is the strength of its community institutions, churches, American Legion lodge hall, and especially the

school. The school campus contains two eras: the classic frame country school of the homesteading era, with additions, and then the more ranch-styled flat roof school building common in American suburbs in the 1950s and 1960s.

As discussed earlier in this blog, Hi-Line residents also make their presence known by signs, even if they are a little worn or emblematic of the loss of other community buildings. Galata is no exception.