At the state history conference in Helena next month, the almost complete new museum at the Montana Historical Society will be unveiled. (The completed museum will have its full public opening in December.) while we won’t be able to see everything yet I’m still looking forward to a peak behind the curtain.

It will be a transformational change for state history—a new platform to explore, interpret and preserve the state’s past. Why do I have such confidence—I was already part of such a project in the creation of a new Tennessee State Museum from 2016-2018. The new museum in Nashville has created a huge new platform for all types of activities in state history and everyone is benefiting, especially the state’s robust heritage tourism industry.

But before we get too excited about the future, let’s remember how this new change at MHS is just the latest chapter in how this amazing institution has served Montana. For this post I’m using some photographs but mostly postcards that I collected in Montana in the 1980s.

The Veterans and Pioneers Memorial Building dates to 1953. Here are two views, one emphasizing the Liberty Bell installation from the Bicentennial and the second reminding us how the tour train, established in 1954, started its tours there and connected visitors to downtown.

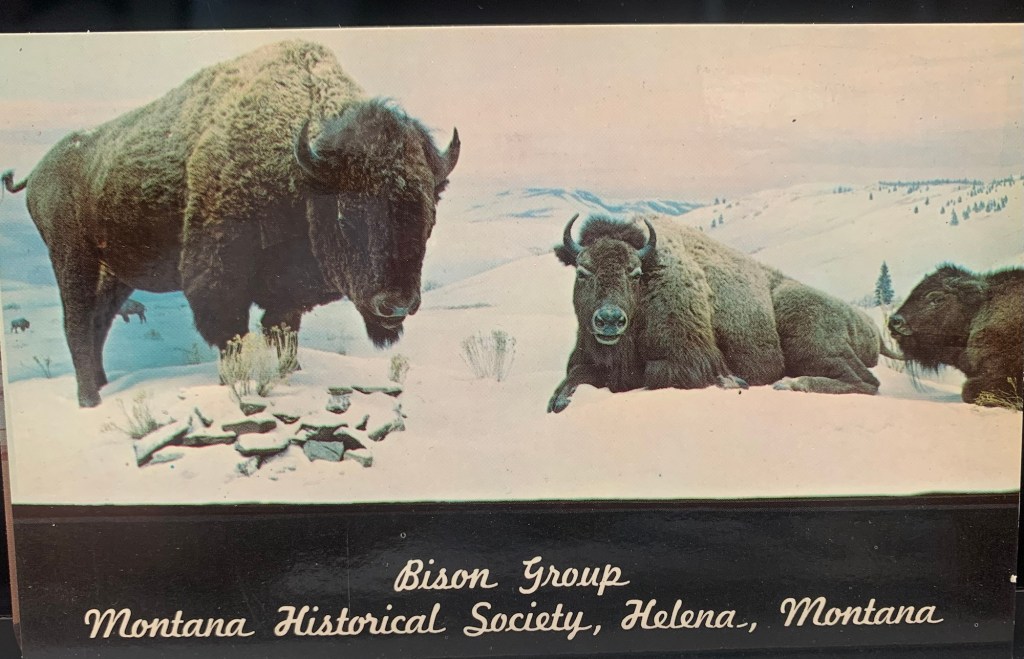

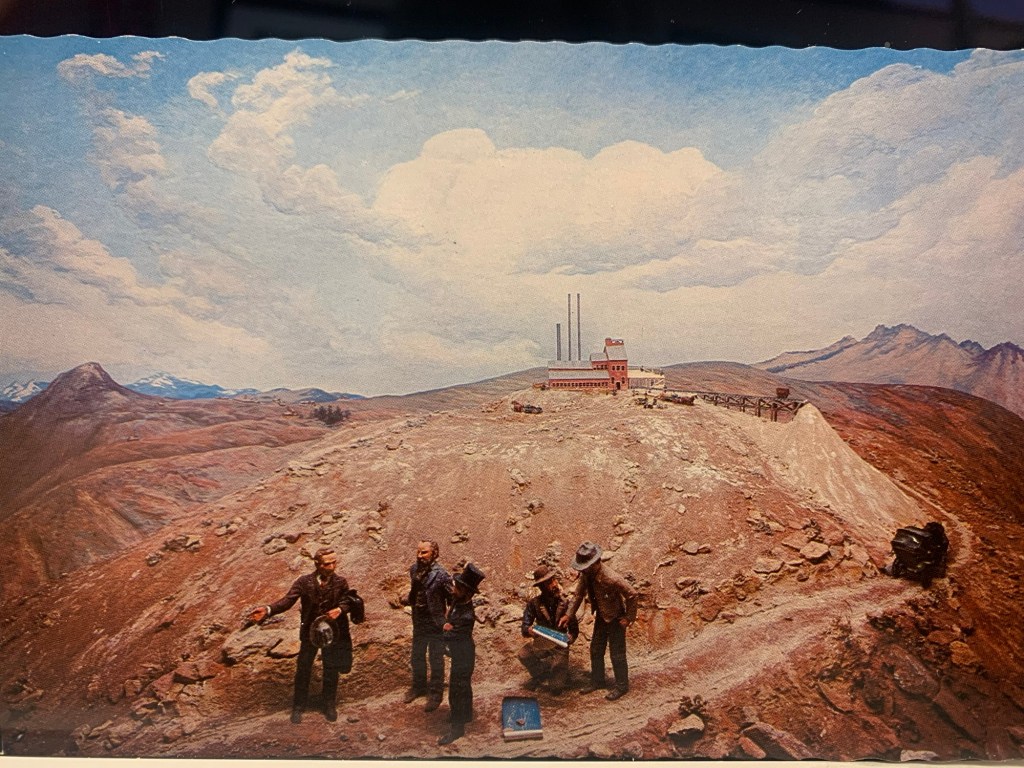

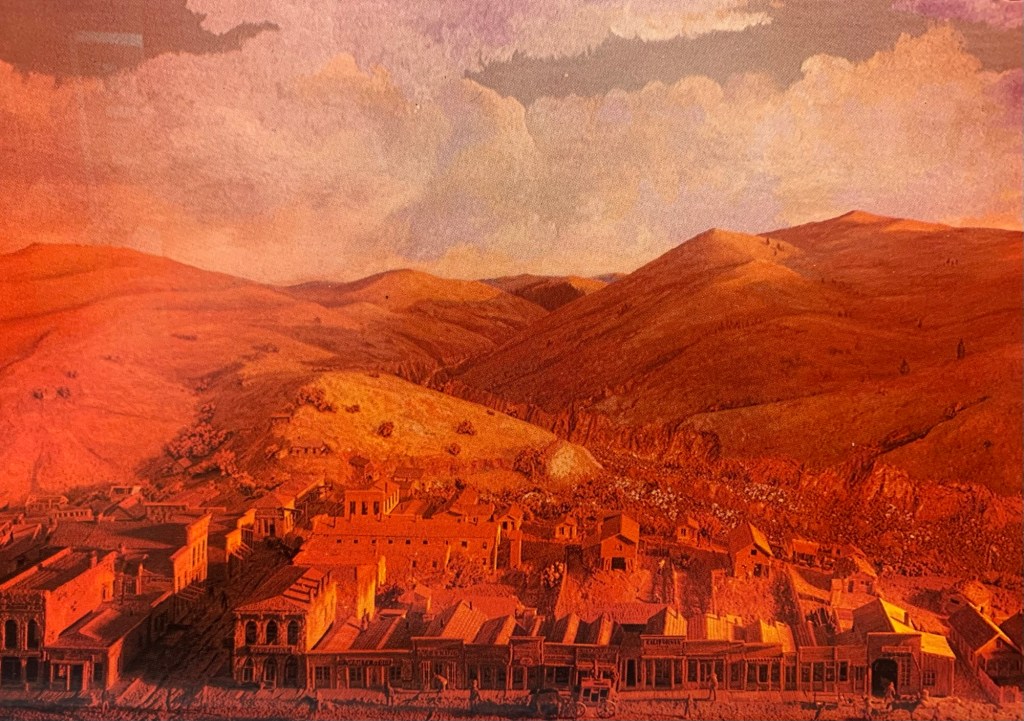

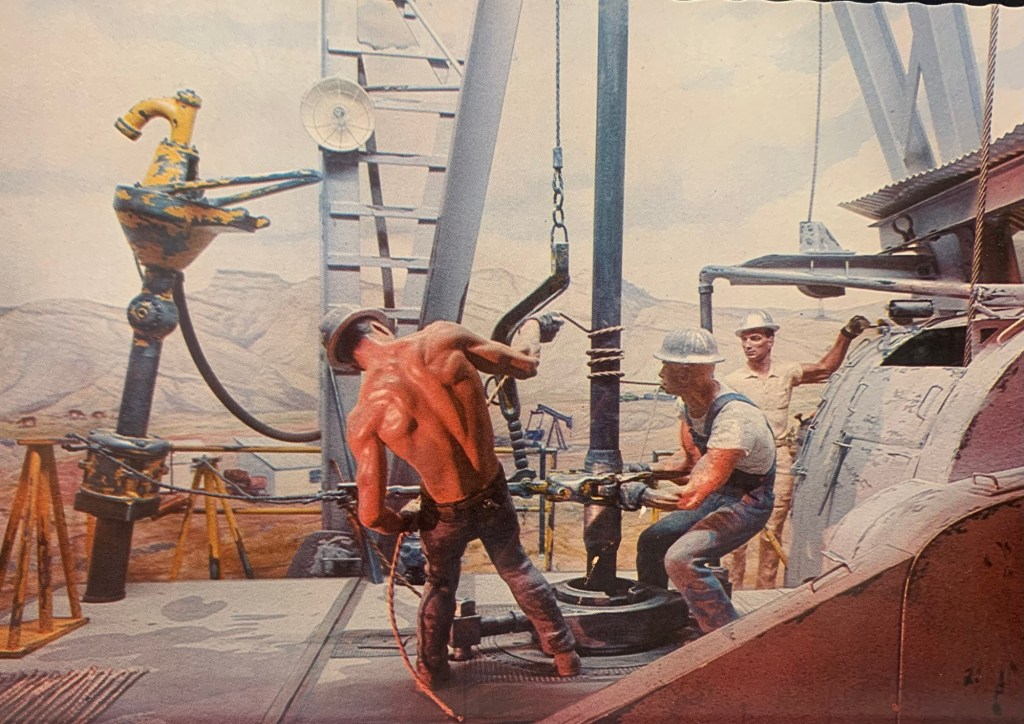

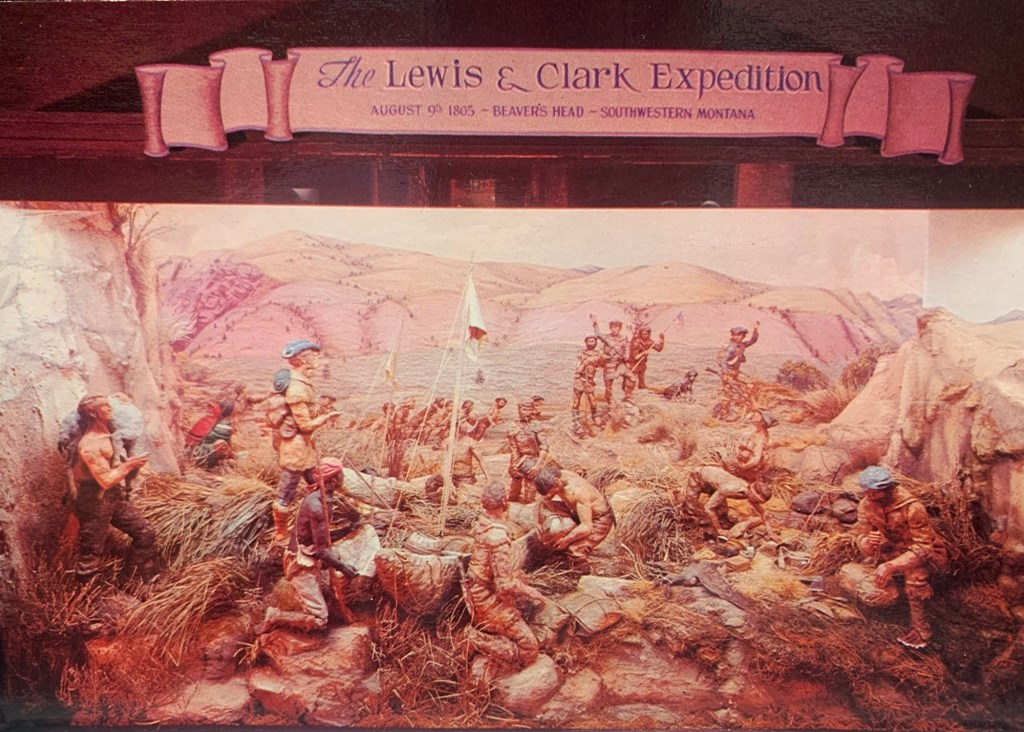

Some of us are old enough to remember the early exhibits—and the dominance of dioramas, dioramas, dioramas!

The highlight of the collection, then and now, was the Charles M. Russell gallery, although his work seemed out of sorts with the modern style of the building.

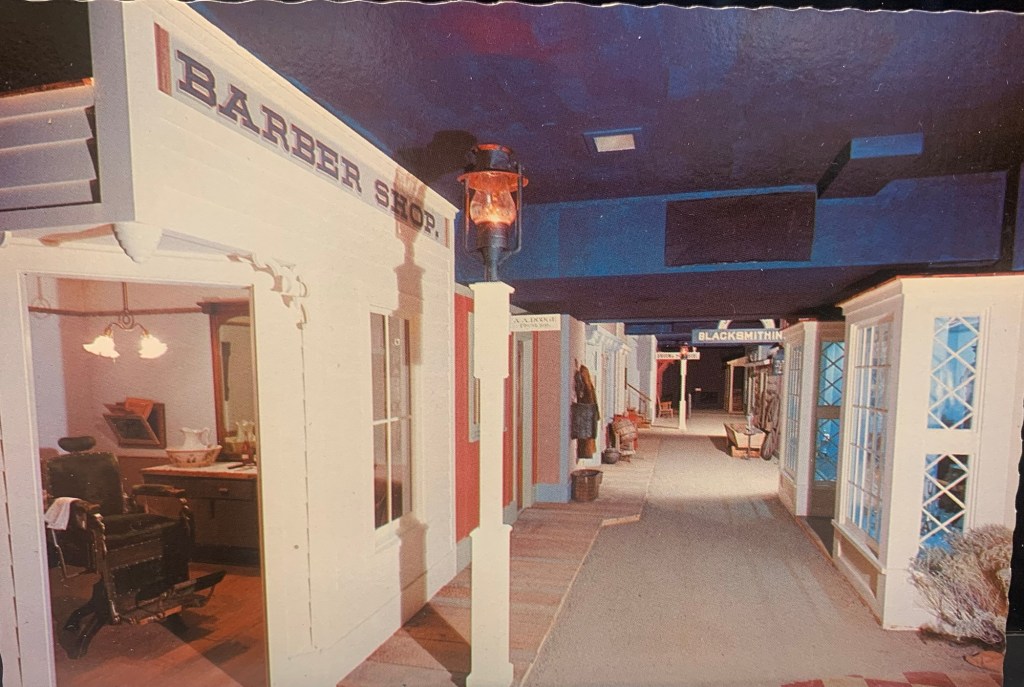

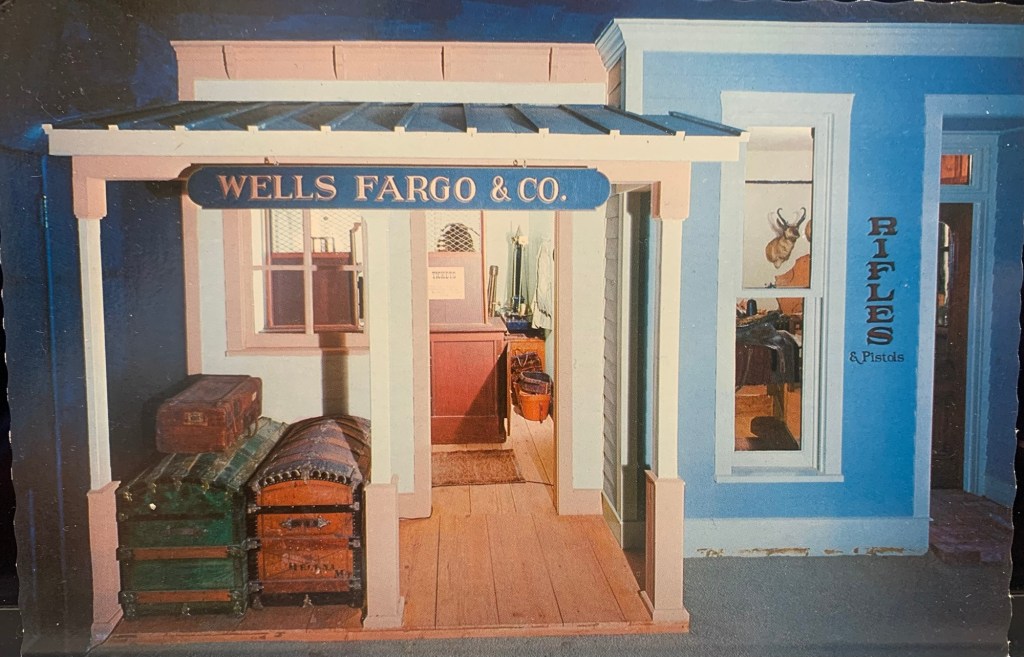

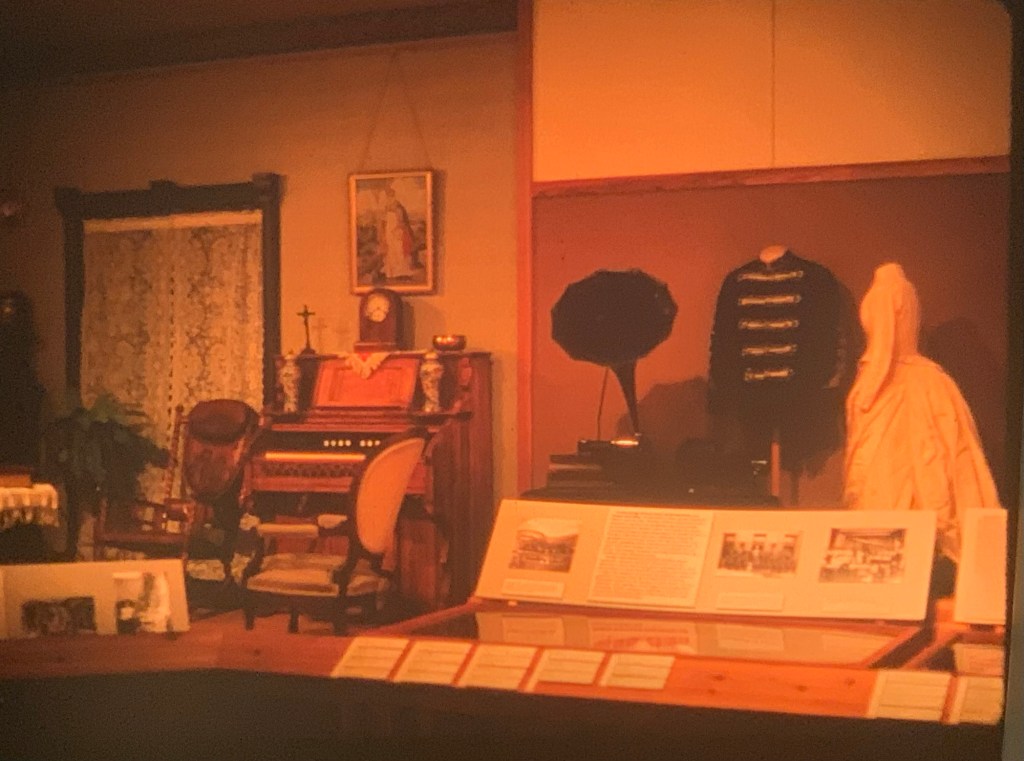

Then in the 1970s came the first transformation—placing Territorial Junction in the basement, a series of period rooms themed to a certain business or activity.

This installation had a tremendous influence on the many county museums that were built in the 1970s and 1970s as so many had their own territorial junction sections.

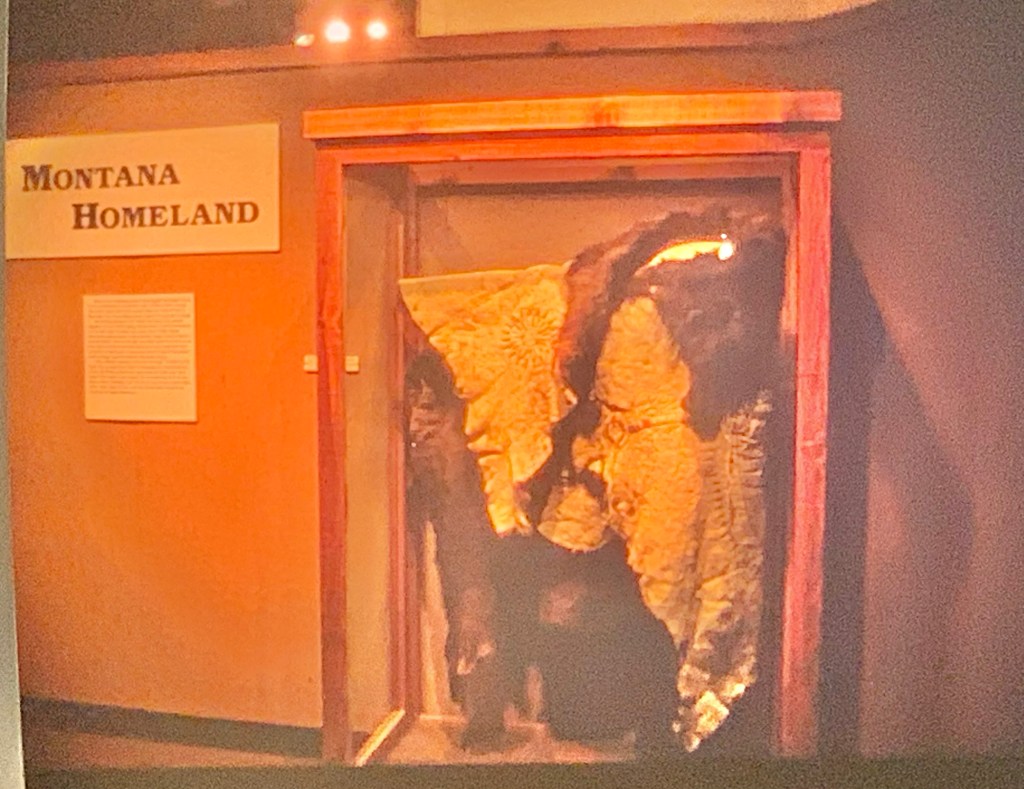

In the mid-1980s MHS staff planned and installed a new history gallery, named Montana Homeland. I visited it in 1988 and took a few slides—and in the dark light my images aren’t great but there’s enough to see how the approach had changed.

The new exhibit highlighted objects from the extensive and valuable MHS collections on Native American history.

Everywhere, from the sections on steamboats to the Victorian era to a 1930s kitchen, objects dominated the senses. It was a visual feast, an approach that I expect the new museum to continue but probably in a much more interactive way.

Yes, no doubt I will miss the old MHS museum but I’m pumped about the new one. What an opportunity! I will report more on this topic after September’s conference.