To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings.

The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

As true in so many turn of the century neighborhoods, various community institutions were crucial to growth and development and historic churches and schools help to define the place even if they are used for different purposes today.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

The East Pine Street historic district is on the north side of the Clark’s Fork River, and its long, linear plan reflects the planning assumptions of what is often called the City Beautiful Movement of the turn of the century–that homes should be set on large lots, with a boulevard-type median dividing the street, giving an urban environment a bit of a country estate feel. Governor Joseph Dixon hired A. J. Gibson to build his mansion along the street and the neighborhood long held the reputation as the city’s most exclusive.

But the grand architectural statement is not the only defining feature of the East Pine Street neighborhood–here too are more vernacular variations from the 1870s to 1900 domestic architecture, while stuck here and there you also find mid-20th century modern styles anchoring the neighborhood.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

Fort Missoula has the Missoula ‘s oldest cemetery but the city cemetery developed within a year of the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The entrance gates were erected in 1905. The cemetery reflects the design ideas of the 19th century Rural Cemetery Movement , with curvilinear drives, large canopies of trees, and an overall naturalistic, serene setting.

Fort Missoula has the Missoula ‘s oldest cemetery but the city cemetery developed within a year of the arrival of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The entrance gates were erected in 1905. The cemetery reflects the design ideas of the 19th century Rural Cemetery Movement , with curvilinear drives, large canopies of trees, and an overall naturalistic, serene setting.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

As expected, there are many grave markers from the 1890s to the 1930s, and several good representative examples of the mortuary art associated with the late Victorian and early 20th century eras.

The fraternal organizations of the late 19th century also are well represented, with the Masonic marker given a primary location within the cemetery’s looping driveways. Its symbolism of the broken column is matched by that of the Order of the Eastern Star.

I must admit that my favorite monument in the cemetery returns us to a theme that I have discussed across the state–the importance of remembering and commemorating the Civil War in late 19th and early 20th century Montana. Monuments related to this theme were another under-explored aspect of my 1984-1985 work; today I remain intrigued by just how much Civil War memorialization exists in Montana.

The Missoula City Cemetery’s obelisk marker takes on added meaning due to its relative scarcity. In 1905, the Women’s Relief Corps, an auxiliary of the post-war Grand Army of Republic, erected this memorial. Scholarship is relatively scant on the Women’s Relief Corps, although a colleague of mine, Dr. Antoinette van Zelm, is making headway on this issue. Compared to the pro-South United Daughters of the Confederacy, the WRC is little recognized today. But this marker shows their devotion to Union veterans buried at the City Cemetery.

Downtown Missoula’s architectural wonders make it a distinctive urban Western place. Let’s start with my favorite, the striking Art Moderne styled Florence Hotel (1941) designed by architect G.A. Pehrson. Located between the two railroad depots on Higgins Street, the hotel served tourists and residents as a symbol of the town’s classy arrival on the scene–it was the first place with air-conditioning–of a region transforming in the 1940s and 1950s.

Downtown Missoula’s architectural wonders make it a distinctive urban Western place. Let’s start with my favorite, the striking Art Moderne styled Florence Hotel (1941) designed by architect G.A. Pehrson. Located between the two railroad depots on Higgins Street, the hotel served tourists and residents as a symbol of the town’s classy arrival on the scene–it was the first place with air-conditioning–of a region transforming in the 1940s and 1950s. With the coming of the interstate highway in the 1970s, tourist traffic declined along Higgins Street and the Florence Hotel was turned into offices and shops, a function that it still serves today.

With the coming of the interstate highway in the 1970s, tourist traffic declined along Higgins Street and the Florence Hotel was turned into offices and shops, a function that it still serves today. Next door is another urban marvel, the Wilma Theatre, which dates to 1921 and like the Florence it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The building was the city’s first great entertainment landmark (even had an indoor swimming pool at one time) but with offices and other business included in this building that anchored the corner where Higgins Street met the Clark’s Fork River. Architects Ole Bakke and H. E. Kirkemo designed the theatre in the fashionable Renaissance Revival style, with a hint towards the “tall buildings” form popularized by architect Louis Sullivan, the building later received an Art Deco update, especially with the use of glass block in the ticket booth and the thin layer of marble highlighting the entrance.

Next door is another urban marvel, the Wilma Theatre, which dates to 1921 and like the Florence it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The building was the city’s first great entertainment landmark (even had an indoor swimming pool at one time) but with offices and other business included in this building that anchored the corner where Higgins Street met the Clark’s Fork River. Architects Ole Bakke and H. E. Kirkemo designed the theatre in the fashionable Renaissance Revival style, with a hint towards the “tall buildings” form popularized by architect Louis Sullivan, the building later received an Art Deco update, especially with the use of glass block in the ticket booth and the thin layer of marble highlighting the entrance.

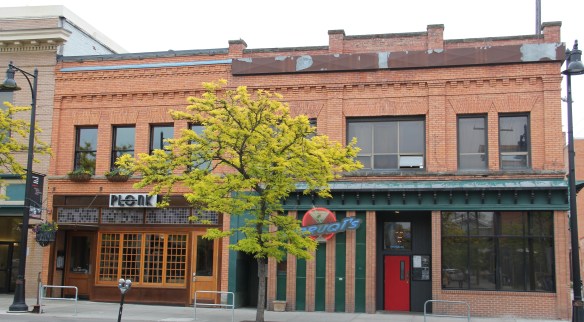

Missoula’s first major department store and entrepreneurial center. The late Victorian era architectural styling of the two-story building also set a standard for many other downtown businesses from 1890 to 1920. These can be categorized as two-part commercial fronts, with the first floor serving as the primary commercial space and the second floor could be offices, dwelling space for the owner, or most common today storage space.

Missoula’s first major department store and entrepreneurial center. The late Victorian era architectural styling of the two-story building also set a standard for many other downtown businesses from 1890 to 1920. These can be categorized as two-part commercial fronts, with the first floor serving as the primary commercial space and the second floor could be offices, dwelling space for the owner, or most common today storage space.

Gibson, the building is one of the state’s best examples of what is called “Beaux Arts classicism,” a movement in the west so influenced by the late 1890s Minnesota State Capitol by architect Cass Gilbert.

Gibson, the building is one of the state’s best examples of what is called “Beaux Arts classicism,” a movement in the west so influenced by the late 1890s Minnesota State Capitol by architect Cass Gilbert.

Just as impressive, but in a more Renaissance Revival style, is the Elks Lodge (1911), another building that documents the importance of the city’s working and middle class fraternal lodges in the early 20th century.

Just as impressive, but in a more Renaissance Revival style, is the Elks Lodge (1911), another building that documents the importance of the city’s working and middle class fraternal lodges in the early 20th century.

Of more recent construction is another federal courthouse, the modernist-styled Russell Smith Federal Courthouse, which was originally constructed as a bank. In 2012, another judicial chamber was installed on the third floor. Although far removed from the classic

Of more recent construction is another federal courthouse, the modernist-styled Russell Smith Federal Courthouse, which was originally constructed as a bank. In 2012, another judicial chamber was installed on the third floor. Although far removed from the classic look, the Russell Smith Courthouse is not out-of-place in downtown Missoula. There are several other buildings reflecting different degrees of American modern design, from the Firestone building from the 1920s (almost forgotten today now that is overwhelmed by its neighbor the Interstate Bank Building) to the standardized designed of gas stations of

look, the Russell Smith Courthouse is not out-of-place in downtown Missoula. There are several other buildings reflecting different degrees of American modern design, from the Firestone building from the 1920s (almost forgotten today now that is overwhelmed by its neighbor the Interstate Bank Building) to the standardized designed of gas stations of 1930s and 1940s, complete with enamel panels and double garage bays, standing next to the Labor Temple.

1930s and 1940s, complete with enamel panels and double garage bays, standing next to the Labor Temple. Modernism is alive and well in 21st century Missoula, with a office tower at St. Patrick’s Hospital, a new city parking garage, and the splashy Interstate Bank building, which overwhelms the scale of the adjacent Missoula Mercantile building–which had been THE place for commerce over 100 years earlier.

Modernism is alive and well in 21st century Missoula, with a office tower at St. Patrick’s Hospital, a new city parking garage, and the splashy Interstate Bank building, which overwhelms the scale of the adjacent Missoula Mercantile building–which had been THE place for commerce over 100 years earlier.

The Silver Dollar, like the Double Front, were meccas not just for railroad workers but also travelers weary of life on the rails and looking for a bit of liquid refreshment. It remains a drinkers’ bar today.

The Silver Dollar, like the Double Front, were meccas not just for railroad workers but also travelers weary of life on the rails and looking for a bit of liquid refreshment. It remains a drinkers’ bar today. I realize that Missoula now has a wide range of downtown establishments–even a wine bar for a good measure–and I wish them well. But give me the Ox, the Double Front, or the Club any day, any time.

I realize that Missoula now has a wide range of downtown establishments–even a wine bar for a good measure–and I wish them well. But give me the Ox, the Double Front, or the Club any day, any time. The Clark’s Fork River and transportation through the valleys and over the Rocky Mountains lie at the core of Missoula’s early history. Captain John Mullan blazed his road through here immediately before the Civil War, and a Mullan Road marker is downtown.

The Clark’s Fork River and transportation through the valleys and over the Rocky Mountains lie at the core of Missoula’s early history. Captain John Mullan blazed his road through here immediately before the Civil War, and a Mullan Road marker is downtown. White settlement first arrived in the initial territorial years and a sawmill was the first major business. As a river crossroads town, Missoula grew, and then became a permanent dot on the federal map with the arrival of Fort Missoula, established in 1877. The fort, largely neglected when I conducted my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984, is now a regional heritage center.

White settlement first arrived in the initial territorial years and a sawmill was the first major business. As a river crossroads town, Missoula grew, and then became a permanent dot on the federal map with the arrival of Fort Missoula, established in 1877. The fort, largely neglected when I conducted my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984, is now a regional heritage center.

Built in 1901, the Northern Pacific passenger station is an impressive example of Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem, and symbolized the turn of the century dominance of the railroad over the region’s transportation and the importance of Missoula to the railroad as a major train yard. The station, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, stands at the historic “top” of downtown Missoula, which at its bare bones has the classic T-plan of a railroad hub of the late 19th century. The Northern Pacific tracks and related railroad warehouses are the top of the “T” stretching in both directions with Interstate I-90 crossing the river bluffs to the northeast. Two reminders of the historic railroad traffic are adjacent to the station–a steam Northern Pacific engine and a diesel Burlington Northern engine.

Built in 1901, the Northern Pacific passenger station is an impressive example of Renaissance Revival style, designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem, and symbolized the turn of the century dominance of the railroad over the region’s transportation and the importance of Missoula to the railroad as a major train yard. The station, listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985, stands at the historic “top” of downtown Missoula, which at its bare bones has the classic T-plan of a railroad hub of the late 19th century. The Northern Pacific tracks and related railroad warehouses are the top of the “T” stretching in both directions with Interstate I-90 crossing the river bluffs to the northeast. Two reminders of the historic railroad traffic are adjacent to the station–a steam Northern Pacific engine and a diesel Burlington Northern engine.

The Milwaukee was not to be out-done by the Northern Pacific when it arrived in Missoula in 1908. Railroad architect J. J. Lindstrand gave the line a fashionable Misson-style passenger station and offices, which opened in 1910. It too is listed in the National Register. Like the company’s stations in Great Falls and Butte, built approximately at the same time, the station has a tall tower that commanded the city’s early 20th century skyline, and made the depot easy to find. Located dramatically along the Clark’s Fork River, the arrival of the railroad and the construction of the depot led to a new frenzy of building on South Higgins Street, and a good many of those one-story and two-story buildings remain in use today.

The Milwaukee was not to be out-done by the Northern Pacific when it arrived in Missoula in 1908. Railroad architect J. J. Lindstrand gave the line a fashionable Misson-style passenger station and offices, which opened in 1910. It too is listed in the National Register. Like the company’s stations in Great Falls and Butte, built approximately at the same time, the station has a tall tower that commanded the city’s early 20th century skyline, and made the depot easy to find. Located dramatically along the Clark’s Fork River, the arrival of the railroad and the construction of the depot led to a new frenzy of building on South Higgins Street, and a good many of those one-story and two-story buildings remain in use today.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

Missoula County has grown, a lot, since my state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985, especially in the county seat of Missoula and surrounding suburbs. Yet Missoula County still has several spectacular rural drives, like Montana Highway 83 above at Condon, along with distinctive country towns. This post will share some of my favorites.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

The Condon Community Center and adjacent Swan Valley Community Library serve as additional hubs for those living along the lakes and mountains of northeast Missoula County. Both buildings are excellent examples of mid-20th century Rustic style–a look that, in different variations, dominates the Highway 35 corridor.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region.

Condon is also the base for the Condon Work Center, home to the Great Northern Fire Crew, of the Flathead National Forest. Here you can take a mile-long Swan Ecosystem Trail and learn of the diversity of life in this national forest region. South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style.

South of Condon on Montana Highway 83 is Seeley Lake–a place that certainly has boomed in the last 30 years–witness the improved highway, new businesses, and population that has increased over 60 percent since my last visit in 1992. Yet it still had places rooted in the community’s earlier history such as the Sullivan Memorial Community Hall–a good example of mid-20th century Rustic style. And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

And it had added one of my favorite bits of roadside architecture in this part of Montana: the Chicken Coop Restaurant as well as opening a new Seeley Lake Historical Museum and Chamber of Commerce office at a spectacular highway location just outside of town.

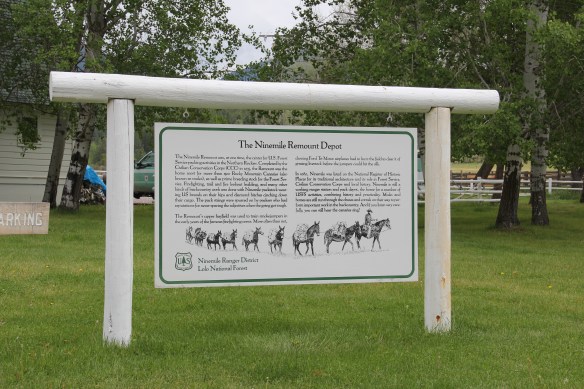

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

I don’t recall even thinking about the forest service facility, but here was an entire complex devoted to the forest service’s use of mules and horses before the days of the ATV that was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps. The remount depot is an interesting

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark.

The name Frenchtown dates to 1868 and is a reference to a number of French Canadians who moved here in the early settlement period. A National Register-listed church, the St. John the Baptist Catholic Church (1884) marks that first generation of settlers. Its classical-tinged cupola has long been the town’s most famous landmark. The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

The Milwaukee Road built through here in 1907-1908 and there remains a handful of historic business buildings from the time of the Milwaukee boom. There is one landmark

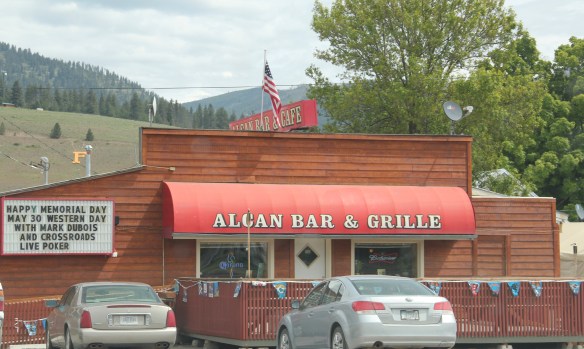

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

another roadside landmark–the Bucksnort Bar, just further evidence to add to the Chicken Coop and the Alcan that you won’t go hungry if you explore the small towns of Missoula County.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83. But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana. In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s. Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana. Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers. The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex. The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

At this time, my entry on Flaxville, the tiny place above in Daniels County, has received the most views. Perhaps that changes as I continue to move into the northwest portion of the state, starting with one of the most rapidly changing places in the last 30 years, Missoula County.

At this time, my entry on Flaxville, the tiny place above in Daniels County, has received the most views. Perhaps that changes as I continue to move into the northwest portion of the state, starting with one of the most rapidly changing places in the last 30 years, Missoula County. I am on the back end of my trek across the Big Sky Country, with probably 50 entries to go–see you soon!

I am on the back end of my trek across the Big Sky Country, with probably 50 entries to go–see you soon! Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Montana Highway 141 cuts north from Avon On U. S. Highway 12 to halfway between the towns of Ovando and Lincoln on Montana Highway 200. Its is high mountains prairie travel at its best, although the height of ranching along this route disappeared a while back. About 12-13 miles north of Avon you cross into the Nevada Creek drainage, which has long watered the land, enhanced after the New Deal added the Nevada Creek earthen dam that created Nevada Creek Reservoir in 1938.

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Along the east banks of the lake are remnants of the Fitzpatrick Ranch, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. I highlighted the property in my book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History (1986). Jimmy Isbel established the property in 1872,

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Thirty years ago, this significant collection of vernacular buildings was in good condition, but the years since have been hard on the property, and the complex now needs serious preservation attention. The loss of the roof on the log barn, and the general poor condition of the roofs of the outbuildings are major concerns.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.

Between the Fitzpatrick Ranch and Helmville is the Barger Ranch, also from the late 19th century judging from the more polished example of Queen Anne style in the ranch house. It is living proof that not all of the Nevada Creek ranches have passed away. The Nevada Creek Water Users Association at Helmville still operates to distribute the invaluable water from the reservoir.  Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville was another topic in my 1986 book. Throughout the Nevada Creek drainage, you could help but be impressed with the log construction, and the various types of notching used for the buildings. Helmville had a particular interesting grouping of wood frame and log buildings, which were highlighted by a 1984 photograph in the book. That exact view could not be replicated 30 years later but several of the old buildings still stood.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Helmville has a good bit of continuity. Along with the row of buildings on Montana 271 there is a turn of the 20th century gable-front cottage and a two-story lodge building that has been turned into a garage.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

Trixie’s was the same fun dive that I always recalled, but the village’s historic buildings had been restored, looking good. Business appeared to be brisk. A new community church has been opened, and a major interpretive place for the “Lewis Minus Clark” expedition had been installed. Kudos to both the U.S. Forest Service and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail for allowing a bit of humor in this marker.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels.

The school had also expanded from its New Deal core of the 1930s, courtesy of the Works Progress Administration. But the most noticeable change was the town’s street signs–first the fact that a small place had street signs but then the nostalgic backpacker theme of these cast iron marvels. Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Ovando is a good location on the Blackfoot River for sportsmen, anglers, and hikers headed into the Bob Marshall Wilderness–its recent change demonstrates the influence on those groups on the 21st century Montana landscape.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Between Garrison Junction, where U.S. Highway 12 and Interstate I-90 meet, to Elliston, at near the Mullan Pass over the continental divide, is a beautiful, historic valley carved by the Little Blackfoot River. It is a part of Powell County that hundreds whiz through daily as they drive between Missoula and Helena, and it is worth slowing down a bit and taking in the settlement landscape along the way.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

Captain John Mullan came this way shortly before the Civil War as he built a military road between Fort Benton and Walla Walla, Washington. A generation later, in the early 1880s, the tracks of the Northern Pacific Road used the Mullan Pass to cross the divide and then followed the Little Blackfoot River west towards Missoula.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters.

The oldest federal imprint in Elliston comes from the ranger’s headquarters for the Helena National Forest in its combination of a frame early 20th century cottage and then the Rustic-styled log headquarters. The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory.

The next railroad town west is Avon, which is also at the junction of U.S. Highway 12 and Montana Highway 141 that takes travelers northwest toward the Blackfoot River. Like Elliston, Avon has several buildings to note, although the National Register-listed property is the historic steel truss bridge that crosses the Little Blackfoot River and then heads into ranch territory. The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century.

The bridge is a Pratt pony truss, constructed in 1914 by contractor O.E. Peppard of Missoula, and little altered in the last 100 years. As the National Register nomination notes, the bridge’s camelback trusses are unusual and have not been documented in other Montana bridges from the early 20th century. Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

Avon has another clearly National Register-worthy building in its 1941 community hall, a late New Deal era building, which has served the community in multiple ways, as a meeting place for the Avon Grange, a polling place, and a place for celebrations of all sorts, including stage presentations and bands.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history.

The Avon School also has a New Deal era affiliation, with the Works Progress Administration. Although remodeled in the decades since, the school still conveys its early 20th century history. Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses.

Avon even has its early 20th century passenger station for the Northern Pacific Railroad, although it has been moved off the tracks and repurposed for new uses. In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

In front of the depot is the turn of the 20th century St. Theodore’s Catholic Church. The historic Avon Community Church incorporates what appears to be a moved one-room school building as a wing to the original sanctuary.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Another important property in Avon, but one I ignored in 1984-85, is the town cemetery, which also helps to document the community’s long history from the 1880s to today.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.

Heading west from Avon on U.S. Highway 12 there are various places to stop and enjoy the river valley as it narrows as you approach Garrison. I always recalled this part fondly, for the beaverslide hay stackers–the first I encountered in Montana in 1981–and they are still there today, connecting the early livestock industry of the valley to the present.