Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

I ended the project at a far different environment, one of Helena’s downtown historic buildings, just off from Last Chance Gulch.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

Don’t misread me–I spent many, many hours in the town’s Last Chance Mall, and at first I thought it quite brilliant, because as the historian I liked the fact that the walking experience was distracted by various interpretive pieces, depicting cattle drives, placer mining, and early 20th century urban life.

But soon enough I was like long-time residents–the sculptural and interpretive elements were nice enough for tourists–it was the surrounding historic brick environments that proved much more fascinating, and lasting.

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

began at the intersection of Last Chance Gulch and Broadway and then stretched back to new modernist-styled city library and a flashy Federal Building, moving the federal presence from where it had stood for most of the century–on a hill overlooking the gulch

in an Italian Renaissance-styled landmark designed by federal architect James Knox Taylor and constructed in 1904. That building would become a new city-county municipal building, still with a downtown post office.

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

Once you crossed the street, you found yet another downtown–not more historic but more architecturally diverse and without as many 1970s improvements. The gulch is the dominant corridor, with two lanes of traffic, parked cars, and all of the traffic bustle you expected in a historic downtown.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

Gilbert would gain his greatest fame later in his career for the designs of the Woolworth Building in New York City and the U.S. Supreme Court building in Washington, D.C. The Montana Club (1903-1905) comes from the first part of Gilbert’s career, where he pursued multiple design inspirations, from the Richardsonian to the Gothic to the stylish Arts and Crafts approach then described as Mission style.

Certainly this part of downtown has changed over the last 30 years, be it from recent, and quite necessary, preservation work at the Montana Club to jazzy new facades added to commercial blocks along the way.

A whole different world, one of the 21st century, beckons when you walk through the Hill park, with its controversial fountain founded by a local chapter of the United Daughters of the Confederacy, and reach the park’s intersection with Neill Avenue.

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown

anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more

modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.

modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.

All that remained from the Helena I recalled from 1985 was the Moorish Revival Civic Center, a building unique in an architectural style but one that still serves as community gathering spot for the arts and music. Here I experienced the Johnny Cash Show in the early 1980s, among other concerts and events. Downtown Helena now has four layers, and the surrounding neighborhoods had changed too–as we shall explore in future posts.

At first glance, Dutton is like many northern plains railroad towns, located on the Great Northern Railway spur line between Shelby and Great Falls. The false front of Mike’s Tavern, then other plain, functional one-story buildings–we have seen hundreds of similar scenes across the Big Sky Country.

At first glance, Dutton is like many northern plains railroad towns, located on the Great Northern Railway spur line between Shelby and Great Falls. The false front of Mike’s Tavern, then other plain, functional one-story buildings–we have seen hundreds of similar scenes across the Big Sky Country. Then, suddenly, there is the cool mid-century modernism of the Dutton-Brady School (Brady is another neighboring railroad town), a style also embraced by the Bethany Lutheran Church.

Then, suddenly, there is the cool mid-century modernism of the Dutton-Brady School (Brady is another neighboring railroad town), a style also embraced by the Bethany Lutheran Church.

All of Glacier National Park is spectacular, frankly, but as you reach Logan Pass and consider the historic architecture on the east side of the park, often the landscape itself overpowers the man-made environment, be it the modernist visitor center at Logan Pass, above to the left of center of the image, or the Many Glacier Hotel on the north end of the park, below. The manmade is insignificant compared to the grandeur of the mountains.

All of Glacier National Park is spectacular, frankly, but as you reach Logan Pass and consider the historic architecture on the east side of the park, often the landscape itself overpowers the man-made environment, be it the modernist visitor center at Logan Pass, above to the left of center of the image, or the Many Glacier Hotel on the north end of the park, below. The manmade is insignificant compared to the grandeur of the mountains. The reverse is true at East Glacier, where the mammoth Glacier Park Lodge competes with the surrounding environment. The massive log hotel was the brainchild of Louis Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway, who wished for a building that could mirror the earlier 1905 Forestry Hall for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Hill had the vision but architect Samuel L. Bartlett of St. Paul, Minnesota, carried the vision into an architectural plan.

The reverse is true at East Glacier, where the mammoth Glacier Park Lodge competes with the surrounding environment. The massive log hotel was the brainchild of Louis Hill, the president of the Great Northern Railway, who wished for a building that could mirror the earlier 1905 Forestry Hall for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Hill had the vision but architect Samuel L. Bartlett of St. Paul, Minnesota, carried the vision into an architectural plan.

But the long landscaped walkway from the Glacier Park Lodge to the Great Northern passenger station, also themed in Rustic style, let everyone know who was in charge–the railroad, whose influence created the national park and then built the facilities that defined the look of the park for the next 100 years.

But the long landscaped walkway from the Glacier Park Lodge to the Great Northern passenger station, also themed in Rustic style, let everyone know who was in charge–the railroad, whose influence created the national park and then built the facilities that defined the look of the park for the next 100 years.

Conrad, the seat of Pondera County, is a railroad town, although the town’s close proximity to Interstate I-15 means that so many have forgotten the importance of this Great Northern Railway spur line that stretches from Shelby on the main line south to Great Falls.

Conrad, the seat of Pondera County, is a railroad town, although the town’s close proximity to Interstate I-15 means that so many have forgotten the importance of this Great Northern Railway spur line that stretches from Shelby on the main line south to Great Falls.

The town’s 1920s Arts and Crafts/ Chalet style Great Northern passenger station, along with grain elevators, serve as a reminder of the railroad’s importance to transporting the grains from neighboring ranches.

The town’s 1920s Arts and Crafts/ Chalet style Great Northern passenger station, along with grain elevators, serve as a reminder of the railroad’s importance to transporting the grains from neighboring ranches. Facing the depot is a combination symmetrical town, with one story brick buildings, several of them classic western bars, and then a block long T-plan that connects to the historic federal highway U.S. 87.

Facing the depot is a combination symmetrical town, with one story brick buildings, several of them classic western bars, and then a block long T-plan that connects to the historic federal highway U.S. 87.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land. That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery.

That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery. Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

Somehow it is most appropriate that my 300th post for Revisiting the Montana Landscape would find me back at Glacier National Park, especially the west side or Flathead County part of the park. From the first visit in 1982, Glacier always intrigued me–at first because of the tie between park creation and railroad development, then the Arts and Crafts/Chalet architecture associated with the park, and then high mountain Alpine environment. In the years since, I have eagerly grabbed a chance to get a cabin by Lake McDonald and just re-charge for a few days.

Somehow it is most appropriate that my 300th post for Revisiting the Montana Landscape would find me back at Glacier National Park, especially the west side or Flathead County part of the park. From the first visit in 1982, Glacier always intrigued me–at first because of the tie between park creation and railroad development, then the Arts and Crafts/Chalet architecture associated with the park, and then high mountain Alpine environment. In the years since, I have eagerly grabbed a chance to get a cabin by Lake McDonald and just re-charge for a few days. For the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work, however, I did not visit the west side of the park–the bulk of the travel took place between mid-February to mid-May 1984, meaning only the lower elevations such as Apgar Village were accessible. But already the state historic preservation office was aware that a major effort was underway to identify and nominate key properties within the park to the National Register of Historic Places, and by the end of the decade that process was largely complete. The National Park Service identified a range of historic resources from the turn of the 20th century to the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service during the 1960s–Glacier became one of the best studied historic landscapes in all of Montana.

For the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work, however, I did not visit the west side of the park–the bulk of the travel took place between mid-February to mid-May 1984, meaning only the lower elevations such as Apgar Village were accessible. But already the state historic preservation office was aware that a major effort was underway to identify and nominate key properties within the park to the National Register of Historic Places, and by the end of the decade that process was largely complete. The National Park Service identified a range of historic resources from the turn of the 20th century to the Mission 66 program of the National Park Service during the 1960s–Glacier became one of the best studied historic landscapes in all of Montana.

Register as an excellent example of Mission 66-associated architecture within the park. Burt L. Gewalt of the Kalispell firm Brinkman and Lenon was the architect.

Register as an excellent example of Mission 66-associated architecture within the park. Burt L. Gewalt of the Kalispell firm Brinkman and Lenon was the architect. Great Northern officials considered the lodge to be the center of the mountain experience on the park’s west side. From there visitors could take overnight hikes to two other facilities, shown below, the Granite Park Chalet to the northeast or the Sperry Chalet to the southeast of Lake McDonald, both of which are also listed in the National Register.

Great Northern officials considered the lodge to be the center of the mountain experience on the park’s west side. From there visitors could take overnight hikes to two other facilities, shown below, the Granite Park Chalet to the northeast or the Sperry Chalet to the southeast of Lake McDonald, both of which are also listed in the National Register.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

City as one large tourism funnel. After spending a good part of 2006-2007 working with local residents and the Great Smoky Mountains National Park about the heritage and preservation of Gatlinburg, Tennessee–one of the most notorious gateways into any national park–I learned to look deeper than the highway landscape and find some real jewels in each of these Glacier National Park gateway communities.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

At Hungry Horse, however, I did leave the highway and explored the marvelous landscape created by the Hungry Horse Dam and Reservoir, a mid-20th century project by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation. The agency justified the dam as a hydroelectric power project for a growing Flathead County and as a boost to local irrigation. The irrigation side of the project–the real reason the agency exists–never happened and Hungry Horse today is an electric power and recreational project.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I appreciated the vastness of the concrete arch dam–the 11th largest concrete dam in the United States–as well as the beauty of Hungry Horse Reservoir, an under-appreciated tourism asset as anyone in Flathead County will tell you. But again, I let just the size and impact of the dam distract me from some of the details of its construction that, today, are so striking.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

I am concerned, however, about news in September 2015 that Reclamation has contracted for updates and renovation at the Visitor Center–let’s hope that the classic 1950s look of the property is not sacrificed.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

Architect Kirtland Cutter of Spokane was the architect and the chalet design was actually just a smaller scale and less adorned version of the Idaho State Exhibition Building that he had designed for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Cutter is one of the major figures of the Arts and Crafts Movement in the American Northwest and we will look at another of his buildings for the railroad and Glacier in the next post about Lake McDonald Lodge.

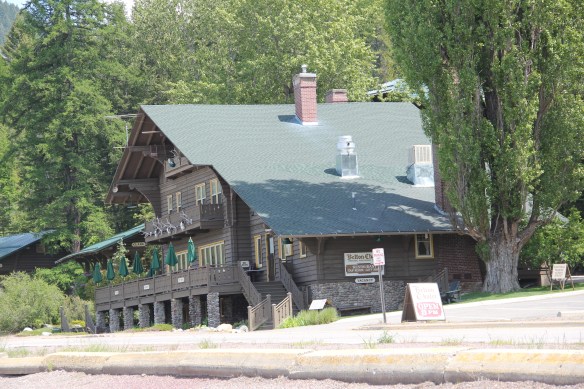

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The answer was yes, to both questions. Here is an early 20th century log building landmark on a highway where the traffic seems to never end. It is also along the corridor of a new recreational system–the Great Northern Rails to Trails linear park that uses an old railroad corridor to connect the city to the country in Flathead County.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

The trail allows bikers to see the rural landscape, still dotted with family farms, of the Smith Valley as it stretches west to Kila, where the old Cottage Inn has been converted in the last few years into the Kila Pub, complete with the Arts and Crafts/Tudor theme associated with the railroad corridor.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

To the north of Kalispell and Whitefish U.S. Highway 93 takes you past the ski developments into a thick forested area, managed in part as the Stillwater State Forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

from the 1920s into the 1960s. While several are from the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s, state ranger Pete De Groat built his log residence in 1928 in the Rustic Style. Stillwater was Montana’s first state forest.

“lone eagles” was local–an attempt to describe those professionals “who fly to work as comfortably as most Americans drive, and whose use of computers in business lets them indulge their preference for life in the great outdoors,” as a June 19, 1994 story in the New York Times explained.

“lone eagles” was local–an attempt to describe those professionals “who fly to work as comfortably as most Americans drive, and whose use of computers in business lets them indulge their preference for life in the great outdoors,” as a June 19, 1994 story in the New York Times explained.

The station along with the railroad tracks defined everything you saw in Whitefish–here in the classic Great Northern T-plan landscape was a classic railroad town–one that old-timers even called the best along the entire line. Whitefish developed and then prospered as a division point on the mainline from 1904 to 1955–and that corporate imprint was still there to be experienced, in 1984.

The station along with the railroad tracks defined everything you saw in Whitefish–here in the classic Great Northern T-plan landscape was a classic railroad town–one that old-timers even called the best along the entire line. Whitefish developed and then prospered as a division point on the mainline from 1904 to 1955–and that corporate imprint was still there to be experienced, in 1984. Thankfully in 2015, I still found all of my favorite landmarks from 30 years earlier, even though there was little doubt that the business district had been altered, sometimes in ways that left little original fabric in place but still some two-story brick blocks stood.

Thankfully in 2015, I still found all of my favorite landmarks from 30 years earlier, even though there was little doubt that the business district had been altered, sometimes in ways that left little original fabric in place but still some two-story brick blocks stood.

A much earlier landmark, the Classical Revival Masonic Temple from the town’s first decade still stood, and it too found a new use through adaptive reuse.

A much earlier landmark, the Classical Revival Masonic Temple from the town’s first decade still stood, and it too found a new use through adaptive reuse. Despite the population boom over the last 30 years, Whitefish still uses its Art Deco-styled school from the New Deal decade of the 1930s, although the auditorium has been restored and updated into a community performing arts center.

Despite the population boom over the last 30 years, Whitefish still uses its Art Deco-styled school from the New Deal decade of the 1930s, although the auditorium has been restored and updated into a community performing arts center.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.