For sheer scale and audacity nothing in Montana built environment rivals the transformations wrought on the Missouri River and the peoples who for centuries had taken nourishment from it than the construction of Fort Peck Dam, spillway, powerhouse, reservoir, and a new federally inspired town from the 1930s to the early 1940s.

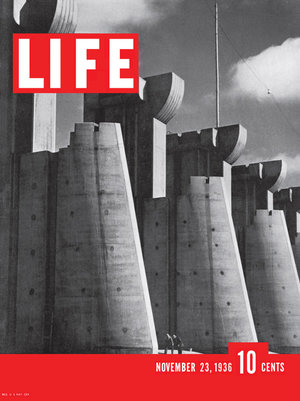

The mammoth size of the entire complex was just as jaw-dropping to me as it had been to the New Dealers and most Americans in the 1930s. That same spillway, for instance, had been the subject of the famous first cover of Life Magazine by Margaret Bourne-White in 1936.

When she visited in 1936 the town of Fort Peck housed thousands but once the job was over, the town quickly diminished and when you take an overview of Fort Peck, the town, today it seems like a mere bump in what is otherwise an overpowering engineering achievement.

Coming from a state that had headquartered another New Deal era transformation of the landscape–the even larger Tennessee Valley Authority project–I understood a good bit of what Fort Peck meant as I started my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984. A good thing I knew a little because outside of a Montana Historic Highway marker and a tour of the power plant there was little in the way of public interpretation at Fort Peck thirty years ago.

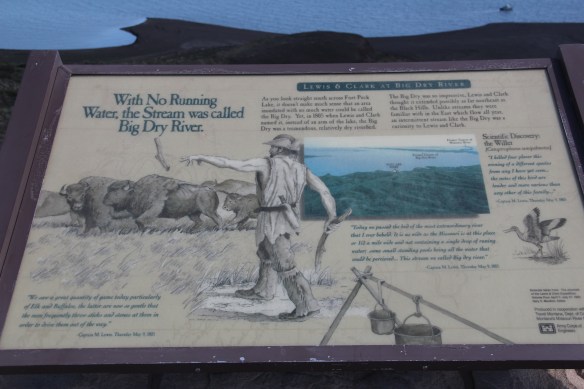

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

The new visitor center at the Fort Peck powerhouses takes the site’s public interpretation to a new level. Just reading the landscape is difficult; it is challenging to grasp the fact that tens of

workers and families were here in the worst of the Great Depression years and it is impossible to imagine this challenging landscape as once lush with thick vegetation and dinosaurs.

Through fossils, recreations, artwork, historic photographs, recreated buildings, and scores of artifacts, the new interpretive center and museum does its job well. Not only are the complications of the New Deal project spelled out–perhaps a bit too heavy on that score, I mean where else do you see what the “Alphabet Agencies” actually meant–but you get an understanding of worlds lost in the name of 20th century progress.

Is everything covered? Far from it–too much in the new public interpretations focuses on 1800 to 1940, and not how Fort Peck has the harbinger of the Cold War-era Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin reject that totally transformed the river and its historic communities. Nor is there enough exploration into the deep time of the Native Americans and what the transformation of the river and the valley meant and still means to the residents of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. There’s still work to be done to adequately convey the lasting transformation that came to this section of Montana in the mid-1930s.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950. Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural

Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City.

statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City. Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive.

at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive. Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor

Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire. The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects.

The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects. The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena.

The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena. Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.

Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.  The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings.

The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings. While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959.

While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959. It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day.

It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day. The public landscape of Anaconda has already been touched on in this blog–places like Washoe Park, the cemeteries, or Mitchell Stadium for instance. Now I want to go a bit deeper and look at public buildings, both government and education in this smelter city.

The public landscape of Anaconda has already been touched on in this blog–places like Washoe Park, the cemeteries, or Mitchell Stadium for instance. Now I want to go a bit deeper and look at public buildings, both government and education in this smelter city. Let’s begin with the only building in Anaconda that truly competes with the stack for visual dominance, the imposing classical revival-styled Deer Lodge County Courthouse. When copper baron Marcus Daly created Anaconda in the 1880s it may have been the industrial heart of Deer Lodge County but it was not the county seat. Daly was not concerned–his hopes centered on gaining the state capitol designation for his company town. When that did not happen, efforts returned to the county seat, which came to Anaconda in 1896. The courthouse was then built from 1898-1900.

Let’s begin with the only building in Anaconda that truly competes with the stack for visual dominance, the imposing classical revival-styled Deer Lodge County Courthouse. When copper baron Marcus Daly created Anaconda in the 1880s it may have been the industrial heart of Deer Lodge County but it was not the county seat. Daly was not concerned–his hopes centered on gaining the state capitol designation for his company town. When that did not happen, efforts returned to the county seat, which came to Anaconda in 1896. The courthouse was then built from 1898-1900.

in Montana is the lavish interior of the central lobby and then the upper story dome. The decorative upper dome frescoes come from a Milwaukee firm, Consolidated Artists. Newspaper accounts in 1900 recorded that the completed courthouse cost $100,000.

in Montana is the lavish interior of the central lobby and then the upper story dome. The decorative upper dome frescoes come from a Milwaukee firm, Consolidated Artists. Newspaper accounts in 1900 recorded that the completed courthouse cost $100,000. The bombastic classicism of the courthouse was at odds with the earlier more High Victorian style of City Hall, built 1895-1896, and attributed to J. H. Bartlett and Charles Lane. But classicism in the first third of the 20th century ruled in Anaconda’s public architecture, witness the Ionic colonnade of the 1931-1933 U.S. Post Office, from the office of Oscar Wenderoth.

The bombastic classicism of the courthouse was at odds with the earlier more High Victorian style of City Hall, built 1895-1896, and attributed to J. H. Bartlett and Charles Lane. But classicism in the first third of the 20th century ruled in Anaconda’s public architecture, witness the Ionic colonnade of the 1931-1933 U.S. Post Office, from the office of Oscar Wenderoth.

Once Anaconda, bursting at the seams following the boom of World War II, chose to upgrade its public schools, it took a decided turn away from traditional European influenced styles and embraced modernism, as defined in Montana during the 1950s.

Once Anaconda, bursting at the seams following the boom of World War II, chose to upgrade its public schools, it took a decided turn away from traditional European influenced styles and embraced modernism, as defined in Montana during the 1950s. The long, lean facade of Lincoln Elementary School (1950) began the trend. Its alternating bands of brick punctuated by bands of glass windows was a classic adaptation of International style in a regional setting. The modernist bent continued in 1950-1952 with the Anaconda Central High School, the private Catholic school, now known as the Fred Moody middle school, only a few blocks away. Except here the modernist style is softened by the use of local stone, giving it a rustic feel more in keeping with mid-20th century sensibilities and the Catholic diocese’s deliberate turn to modern style for its church buildings of the 1950s and 1960s (see my earlier post on College of Great Falls).

The long, lean facade of Lincoln Elementary School (1950) began the trend. Its alternating bands of brick punctuated by bands of glass windows was a classic adaptation of International style in a regional setting. The modernist bent continued in 1950-1952 with the Anaconda Central High School, the private Catholic school, now known as the Fred Moody middle school, only a few blocks away. Except here the modernist style is softened by the use of local stone, giving it a rustic feel more in keeping with mid-20th century sensibilities and the Catholic diocese’s deliberate turn to modern style for its church buildings of the 1950s and 1960s (see my earlier post on College of Great Falls).