Kalispell is the seat of Flathead County, established on the Great Northern Railroad line in the 1890s. Today the city is the hub for commerce, transportation and medical care in northwest Montana. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation designated it as a Preserve America community in recognition of its historic downtown and multiple National Register of Historic Places properties.

Certainly the town has many impressive late Victorian era buildings, like the County Courthouse, but this post focuses on a part of Kalispell’s historic built environment that doesn’t get enough attention—its buildings of modern 20th century styles.

The key town founder was C. E. Conrad and similar to how he started the town, you could also say he started the modernist traditions by commissioning his grand Shingle-style mansion from architect A.J.Gibson in 1895. Architectural historians consider the Shingle style, introduced by major American architects Henry Hobson Richardson and the New York Firm McKim, Mead, and White, to be an important precursor to the modernist buildings that would flourish in Kalispell during the 1930s.

Another important example of early modernist style is this local adaptation of Prairie house style, a form introduced and popularized by the designs of American master Frank Lloyd Wright.

Kalispell’s best modernist examples come from the 1930s to 1960s. In 1931 Brinkman designed the KCFW-TV building in a striking Art Deco style. It was originally a gas station but has been restored as an office building with its landmark tower intact.

The Strand Theatre closed as a movie house in 2007 but its colorful Art Deco marquee and facade remain, another landmark across the street from the History Museum which is housed in the old high school.

The Eagles Lodge (1948-1949) is an impressive example of late Art Deco style, especially influenced by the federal “WPA Moderne” buildings from the New Deal. G.D. Weed was the architect.

Then the town opened Elrod School in 1951. It is a good example of mid-century International style in a public building.

The 1950s decade witnessed new modern style religious buildings. The Central Bible Church (1953) evolved from a merger of Central Bible and the West Side Norwegian Methodist Church. Harry Schmautz was the architect.

That same year, the Lutheran church added a new wing for its youth ministry, the Hjortland Memorial, which is one of Kalispell’s most impressive 1950s design. Ray Thone was the architect.

In 1958 Central Christian Church completely remodeled its earlier 1908 building to a striking modern design.

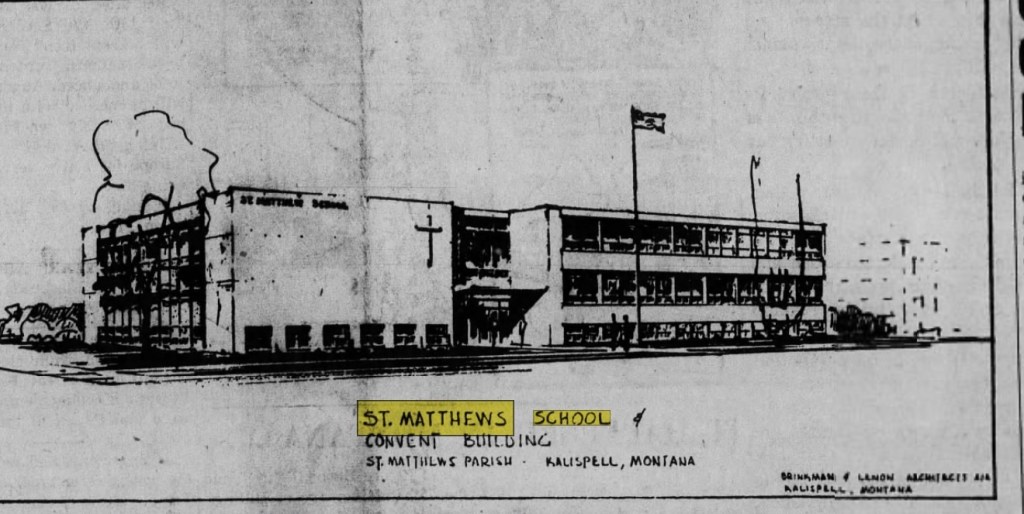

That same year came the opening of St. Matthew Catholic School, an impressive two-story example of International style in an institutional building. the architect was the firm of Brinkman and Lenon.

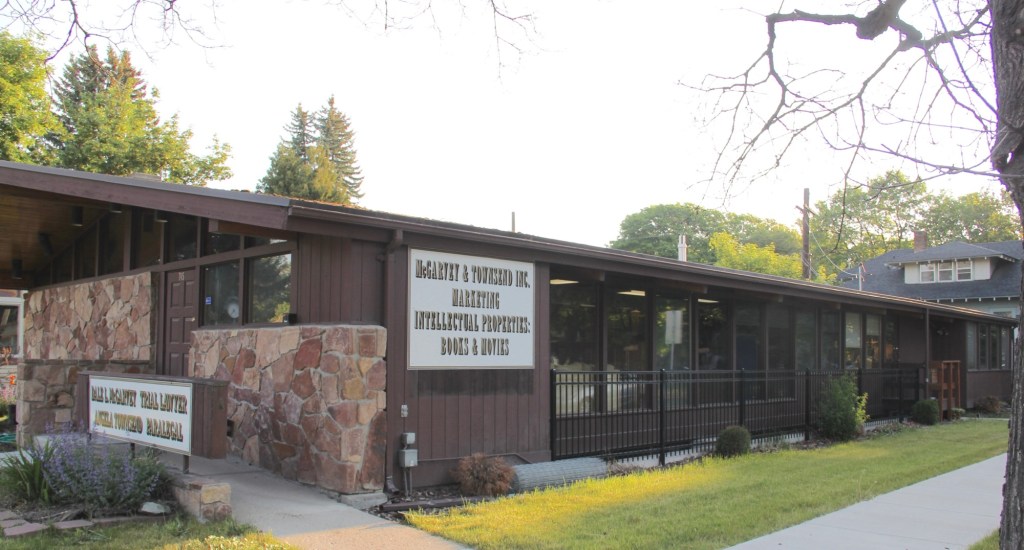

Kalispell also has two excellent examples of commercial buildings in the mid-century contemporary style. Below is the stone veneer and window wall of the McGarvey and Townsend building.

But my favorite, until a recent “remuddling,” is the Sutherland Dry Cleaners, now a golf supply shop.

Kalispell has several good examples of mid-century domestic design. My favorite is this Ranch-style residence near the Conrad Mandion.

This post doesn’t include all of Kalispell’s modernist designs but hopefully I have included enough to demonstrate that the town has a significant modernist architecture tradition.

The earlier homes in the district are mostly Victorian in style and form, like the dwellings at 707 N. Meade (below) and 709 N. Kendrick (second below), the most Queen Anne style dwelling that I recorded in 1988 in Glendive.

The earlier homes in the district are mostly Victorian in style and form, like the dwellings at 707 N. Meade (below) and 709 N. Kendrick (second below), the most Queen Anne style dwelling that I recorded in 1988 in Glendive.

A good bit of the historic machine shops (above) still operated in 1988. The depot and railroad offices still dominated the Merrill Avenue business district (below).

A good bit of the historic machine shops (above) still operated in 1988. The depot and railroad offices still dominated the Merrill Avenue business district (below).

My favorite Merrill Avenue business was the wonderful Art Moderne style of the Luhaven Bar (below). You gots love the black carrera glass and glass block entrance.

My favorite Merrill Avenue business was the wonderful Art Moderne style of the Luhaven Bar (below). You gots love the black carrera glass and glass block entrance.

But my favorite modernist building was the First National Bank, which was later converted to the town’s public library.

But my favorite modernist building was the First National Bank, which was later converted to the town’s public library. Next posting will include homes from the town’s residential district from the early 20th century to the mid-century as I continue a look back to the Yellowstone River and its towns in 1988.

Next posting will include homes from the town’s residential district from the early 20th century to the mid-century as I continue a look back to the Yellowstone River and its towns in 1988.