Virginia City in the 19th century was a living, breathing place, and continues so today. After all it is not all a recreated outdoor museum, it is the location, still, of the Madison County Courthouse and is the seat of Madison County. The courthouse is one of the great 19th century public buildings of Montana.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today.

Nevada City, just a stone’s throw away, was and is different. Here stood the historic Gothic Revival-styled Finney House, built c. 1863-64, along with about a dozen or so other historic buildings.

There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

Today I think about Nevada City differently. As a historic district of related buildings, placed here in a coherent plan c. 1959-1960 that was designed to convey to the public a range of the western experience during the northern Rockies gold rush era, and to serve smack dab on the side of Montana Highway 287 as a heritage tourism resource, Nevada City is due a re-assessment. These once scattered buildings have established a new context over the last 30 years. And, like in Virginia City, the Montana Heritage Foundation is doing what it can to repair and conserve this unique built environment.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Behind the fenced barriers of the outdoor museum (unlike several building zoos in the state this place is just not open without barriers for tourists to visit), you can encounter significant properties associated with the vigilante movement, such as this spot associated with the hanging of George Ives in 1863.

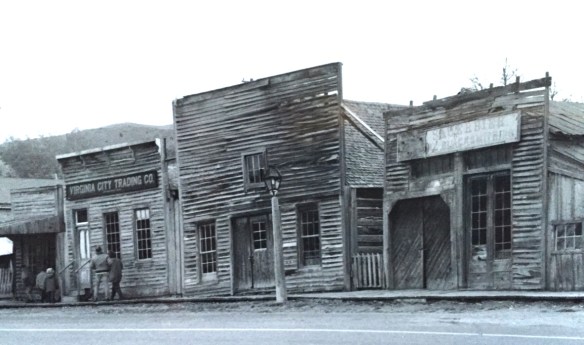

Another theme is vernacular architecture on the gold rush frontier, and how even the mundane false front style of so many buildings at that time could be more elaborate, and expressive. The craftsmanship of the original buildings would need to be carefully assessed to determine whether what you see today reflects 150 years ago or the craftsmanship of restoration 50 years ago.

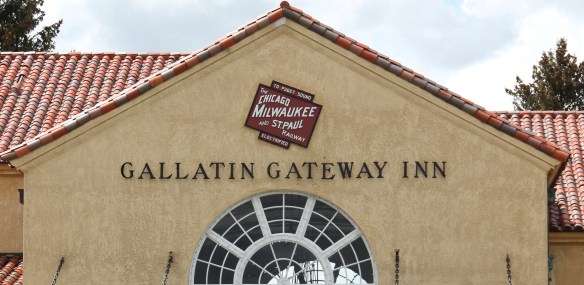

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

Therefore, when in 1984-1985 I made the decision to give Nevada City little more than a nod, that was ok–the restored village effort was then only 20-25 years old. Not very historic, although the buildings came from history. Thirty years later, my thoughts have changed dramatically. Nevada City is much more than a passing interest. In fact, it is a

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one-

U.S. Highway 89 enters the Blackfeet Indian Reservation on its southern border, heading for its junction with U.S. Highway 2 and the reservation center of Browning. Before the junction, you cross the historic Two Medicine River, a historic corridor for the Blackfeet. To the west of the river crossing is a highway historical marker for Coldfeet School, a one- room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

room school (not extant) built for Blackfeet children in 1933 during the New Deal. To the east of the highway river crossing, however, was one of the earliest schools (1889) on the reservation, the Holy Family Catholic

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape.

This panorama of the mission site today shows that neither of the dormitories remain, although the historic frame barn and mill still stand (to the left) while the chapel is still a dominating element, and has been incorporated into present-day Blackfeet culture. It is in excellent shape. Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Another change is that the Blackfeet provide public interpretation of the site, through their own historical markers, which is extended into the adjacent historic cemetery, one of the most somber places in the region. The old mission is now part of the reservation’s heritage tourism effort.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College.

Returning to U.S. 89 and heading northwest, you head to the junction of U.S. Highway 2 and the town of Browning. The town is a center for reservation education, as shown by the new campus for the Blackfeet Community College. Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door.

Here too is another historic Catholic Church, the Little Flower Catholic Church, built in 1931, from locally available stone in a Gothic Revival style. The congregation supports a small Catholic school next door. The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

The Browning fairgrounds is an important Blackfeet recreation and cultural center, with this recent installation again providing public interpretation of Blackfeet culture.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015.

and U.S. 89, heading north. It created an appropriate, respectful way for the increasing number of auto tourists headed to Glacier National Park to learn about the Blackfeet in particular and Plains Indian culture in general. The famous mid-20th century anthropologist, John Ewers, had worked tribes to create the museum’s initial exhibits and collections. In the 21st century, the Blackfeet have developed additional institutions to take advantage of tourism through the nearby Glacier Peaks casino and hotel, a complex that has developed from 2011 to 2015. These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

These new buildings are part of a long-term continuum of tourism in Browning, starting with this old concrete tipi, built originally as a gas station in 1934 and now converted into a coffee shop. And the Blackfeet

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

Trading Post is a business found in all sorts of national park gateways–the classic place to get cheap souvenirs and t-shirts of all types, not to mention moccasins and all of the stereotypical material culture of Native American tourism in our country.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago.

the primary voice on what the park means, and how visitors can think about it today. The Native American presence on U.S. Highway 89 today is much more evident, with much more public interpretation, than in my travels 30 years ago. One of my favorite county seats is Choteau, where U.S. Highways 89 and 287 meet. Both of those roads were and are among my favorite to take in the state, and Choteau I quickly found had one of my favorite local dives the Wagon Wheel. Back in the day, however, I did not appreciate how the town’s history and built environment was shaped by the Sun River Irrigation project and the overall growth in the county during the first two decades of the 20th century and later a second boom in the 1940s.

One of my favorite county seats is Choteau, where U.S. Highways 89 and 287 meet. Both of those roads were and are among my favorite to take in the state, and Choteau I quickly found had one of my favorite local dives the Wagon Wheel. Back in the day, however, I did not appreciate how the town’s history and built environment was shaped by the Sun River Irrigation project and the overall growth in the county during the first two decades of the 20th century and later a second boom in the 1940s. Choteau has a different look than most towns from this era of Montana history. The centerpiece of the towns plan is not a railroad depot but the magnificent Teton County Courthouse (1906), which occupies a spot where the two federal highways junction. Designed by architects Joseph B. Gibson and George H. Shanley, the National Register-listed courthouse is made of locally quarried stone in a late interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque style, similar to, but to a much lesser scale and detail, than H. H. Richardson’s own Allegheny County Courthouse (c. 1886) in Pittsburgh.

Choteau has a different look than most towns from this era of Montana history. The centerpiece of the towns plan is not a railroad depot but the magnificent Teton County Courthouse (1906), which occupies a spot where the two federal highways junction. Designed by architects Joseph B. Gibson and George H. Shanley, the National Register-listed courthouse is made of locally quarried stone in a late interpretation of Richardsonian Romanesque style, similar to, but to a much lesser scale and detail, than H. H. Richardson’s own Allegheny County Courthouse (c. 1886) in Pittsburgh.

This historic neoclassical-styled bank building is now home to a coffee shop but other commercial buildings have changed very little, except for the mix of retail business. This is not a dying business district but one with a good bit of jump, of vitality.

This historic neoclassical-styled bank building is now home to a coffee shop but other commercial buildings have changed very little, except for the mix of retail business. This is not a dying business district but one with a good bit of jump, of vitality.

where the historic Bella Vista Motel–a perfect example of a 1950s motel with separate units like tiny Ranch-styled houses–has given way to a c. 2015 conversion into apartments.

where the historic Bella Vista Motel–a perfect example of a 1950s motel with separate units like tiny Ranch-styled houses–has given way to a c. 2015 conversion into apartments.