Over the past couple of years, I have documented several historic cemeteries in Great Falls. But I had missed one, the city’s Jewish Cemetery, and it too is on Highland Road south of the city, and east of the older Highland Cemetery. It’s a bit difficult to find as there are no signs but a metal entrance “gate” shows you the way.

The Jewish community in Great Falls established the cemetery in 1916, a few years after the establishment of the much larger and nearby Highland Cemetery. The Great Falls Hebrew Association owns the property, which according to tax records has ten acres. A 2003 story in the Great Falls Tribune estimated 20 burials but no number is certain. The majority of the intact grave markers are clustered in a row in the western end of the cemetery.

But other markers are scattered across the top half of the cemetery while other family plots had been damaged before the efforts at restoration over the last ten years.

A low metal, open fence marks a family plot erected for Anna and Abraam [is it a misspelling and should be Abraham as newspaper stories suggest?] Bass, probably installed 1931-1932.

Abraam “Abe” Bass was “well known in sporting circles” and identified as a gambler, according to the Great Falls Tribune of May 10, 1931. He had earlier in 1931 been forced to end a lottery that he operated from the Star cigar store in Great Falls. He left the town looking for opportunities in Nevada but died in an automobile accident about 30 miles from Reno, Nevada. His wife Anna had died earlier.

Years of neglect mean that some markers have been damaged. Or perhaps moved, as in the case of the Baby Grossman marker of 1927.

The year 1940 appears to mark the end of the cemetery’s first generation of burials. Max Gold, a retired carpenter, was born in Russia. He lived in Cut Bank for 15 years but as his death in late 1949, the family buried him in Great Falls.

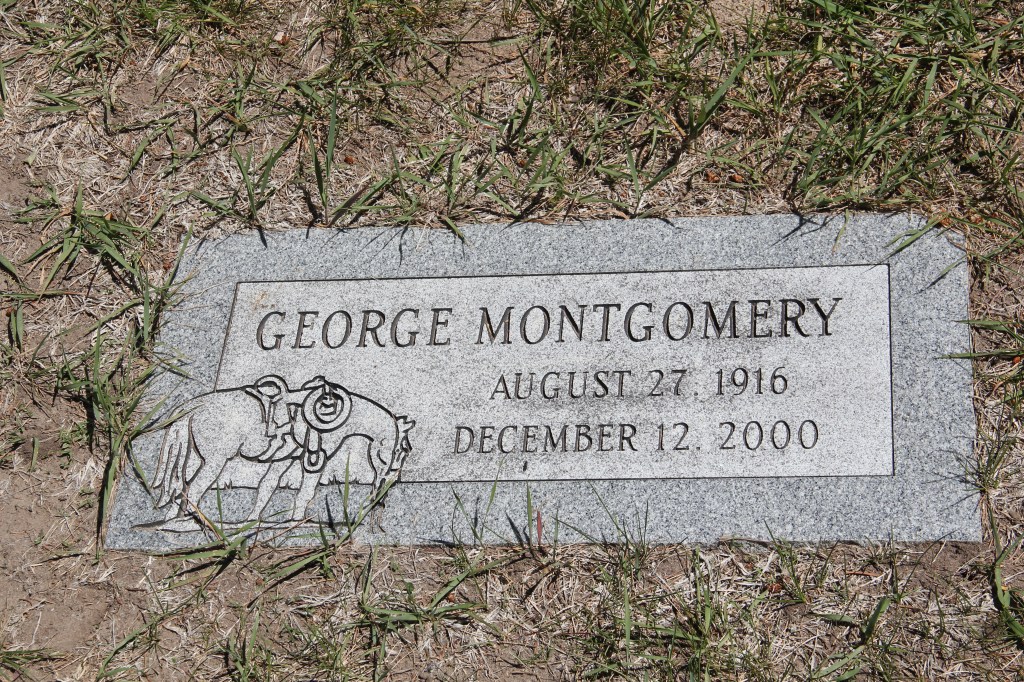

In the 21st century families again began to bury their dead here, with Irving Greenfield in 2000 and Allan Bruce Silverstein in 2012. Perhaps those burials encouraged the Association to begin regular oversight of the property, following its restoration by Max Daniel Weissman as his Eagle Scout service project in 2015.

The Great Falls Jewish Cemetery is an important but once forgotten historic place in Cascade County. We can hope that the good efforts of maintenance continue and that more research is directed to the histories of those buried there.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood. All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the

All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the

supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience.

atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience. Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation. Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

The Missouri River runs through Cascade County and is at the heart of any future Great Falls Heritage Area. This section of the river, and the portage around its falls that fueled its later nationally significant industrial development, is of course central to the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803-1806. The Lewis and Clark story was recognized when I surveyed Cascade County 30 years ago–the Giant Springs State Park was the primary public interpretation available then. But today the Lewis and Clark story has taken a larger part of the public history narrative in Cascade County. In 2003 the nation, state, and city kicked off the bicentennial of the expedition and that key anniversary date spurred the

The Missouri River runs through Cascade County and is at the heart of any future Great Falls Heritage Area. This section of the river, and the portage around its falls that fueled its later nationally significant industrial development, is of course central to the story of the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1803-1806. The Lewis and Clark story was recognized when I surveyed Cascade County 30 years ago–the Giant Springs State Park was the primary public interpretation available then. But today the Lewis and Clark story has taken a larger part of the public history narrative in Cascade County. In 2003 the nation, state, and city kicked off the bicentennial of the expedition and that key anniversary date spurred the

Despite federal budget challenges, the new interpretive center was exactly what the state needed to move forward the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and its many levels of impact of the peoples and landscape of the region. The center emphasized the harrowing, challenging story of the portage around the natural falls of what became Great Falls but its

Despite federal budget challenges, the new interpretive center was exactly what the state needed to move forward the story of the Lewis and Clark expedition, and its many levels of impact of the peoples and landscape of the region. The center emphasized the harrowing, challenging story of the portage around the natural falls of what became Great Falls but its exhibits and programs have significantly broadened our historical understanding of the expedition, especially its relationship with and impact on various Native American tribes from Missouri to Washington.

exhibits and programs have significantly broadened our historical understanding of the expedition, especially its relationship with and impact on various Native American tribes from Missouri to Washington. The contribution of the interpretive center to a greater local and in-state appreciation of the portage route cannot be underplayed. In the preservation survey of 1984, no one emphasized it nor pushed it as an important resource. When threats of development came about in last decade, though, determined voices from preservationists and residents helped to keep the portage route, a National Historic Landmark itself, from insensitive impacts.

The contribution of the interpretive center to a greater local and in-state appreciation of the portage route cannot be underplayed. In the preservation survey of 1984, no one emphasized it nor pushed it as an important resource. When threats of development came about in last decade, though, determined voices from preservationists and residents helped to keep the portage route, a National Historic Landmark itself, from insensitive impacts.

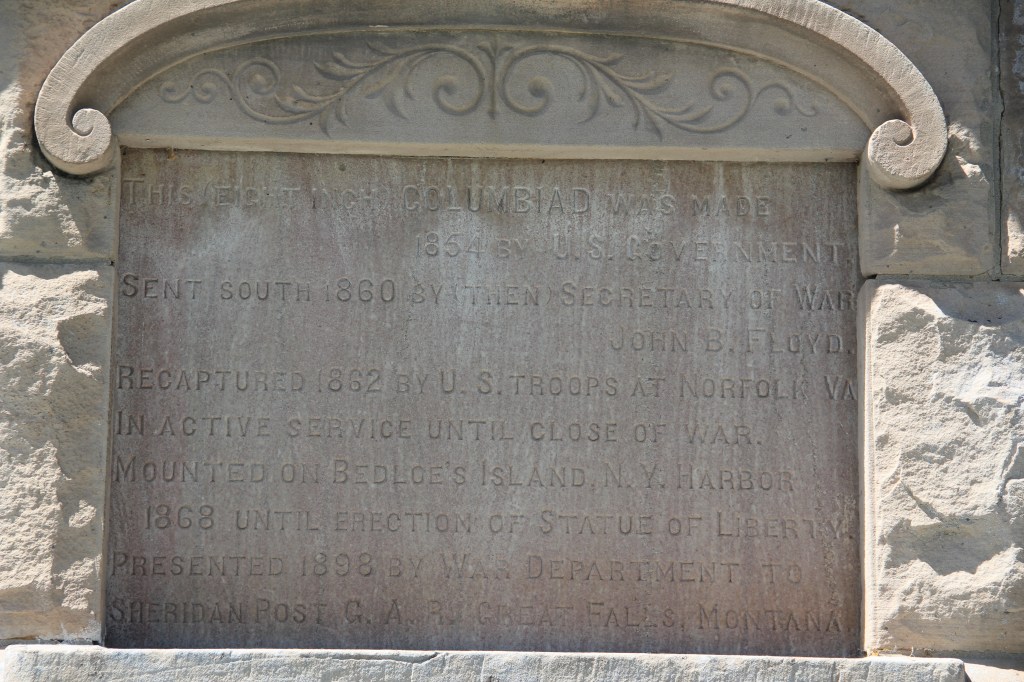

late 1850s. Hundreds pass by the monument near the civic center in the heart of Great Falls but this story is another national one that needs more attention, and soon than later.

late 1850s. Hundreds pass by the monument near the civic center in the heart of Great Falls but this story is another national one that needs more attention, and soon than later.