In February 1984 one of my first assignments on the grand field study of Montana known as the state historic preservation plan survey was to check on the progress of the restoration and reopening of the Grand Union Hotel in Fort Benton.

The work was still underway then, but the result after 30 years of local investment and engagement, assisted mightily by the state historic preservation office and other state groups, is impressive. The Grand Union is a riverfront anchor on one of the nation’s most important river towns in all of U.S. history.

The work was still underway then, but the result after 30 years of local investment and engagement, assisted mightily by the state historic preservation office and other state groups, is impressive. The Grand Union is a riverfront anchor on one of the nation’s most important river towns in all of U.S. history.

The success of the Grand Union is mirrored in another property I visited in my 1984 day and a half in Fort Benton: the reconstructed Fort Benton. There were bits of the adobe blockhouse and walls still standing in 1984, as they had for decades as shown in the old postcard below.

The success of the Grand Union is mirrored in another property I visited in my 1984 day and a half in Fort Benton: the reconstructed Fort Benton. There were bits of the adobe blockhouse and walls still standing in 1984, as they had for decades as shown in the old postcard below.

What the locally administered Museum of the Upper Missouri managed to do was to protect a vitally important site of national significance, and then through its own museum exhibits, try to convey the significance of the place to those who happened to discover it.

In the past 30 years, the museum and its supporters managed to continue protecting the archaeological remnants of the fort but also to rebuild the fort to its mid-19th century appearance. This reconstruction is no small feat, and naturally requires staffing, commitment, and monies to keep the buildings and exhibits in good condition.

A few steps away is another preserved historic building, the I. G. Baker House, built for one of the town’s leading merchants and traders, in weatherboard-disguised abode, in the traditional central hall plan of the mid-19th century. For decades, it has been a passive historic site, opened to the public, with rooms and collections protected by plexiglass. You already have to know much to appreciate the jewel this early bit of domestic architecture represents in understanding the building traditions of the territorial era.

These successful heritage development of the hotel, the fort, and the preservation of the I.G. Baker House, however, has not spurred a greater recognition of the significance of Fort Benton to either national audiences or even residents of the Big Sky Country. When I mention Fort Benton here in the east I typically get blank stares or a quick change of topic. But the town was the westernmost port on the Missouri River, the first interstate exit if you will into the northern plains and northwest. From Fort Benton ran trails and roads into western Canada, Washington State, and into the mines of the Rocky Mountains. The building of the Manitoba Road in the late 1980s eventually meant the town’s importance as a river port was bypassed, but from the mid-19th century into the 1880s, Fort Benton was THE place for commercial expansion, riverboat travel, economic exchange, and the deeper cultural exchanges of the fur trade, with all of those events shaping the national economy and culture. How can such a legacy become diminished? Why? Is it the central Montana location? The lack of national folklore heroes?

Fort Benton is doubly valuable because it is a town with layers, as I have discussed in earlier postings. The town, unlike many of Montana’s early settlements, was no ghost town, instead it was a town with its frontier river port layer, its territorial layer, and its homestead boom layer all competing for attention. The past lives side to side with the present in Fort Benton and thus, it has the potential to shape the future of the town, and this region, in ways that cannot be replicated elsewhere.

Now it is time to stress to our national representatives that it is time for America to cast its eyes, and its support, for the preservation and heritage enhancement of a place that tells so much of the nation’s story. Here at Fort Benton is a living historic town, a place where you can stay a bit and learn how the country has grown, changed, and together can better face our uncertain futures. The residents have made a lasting commitment–it is now time for Fort Benton to reach the national stage.

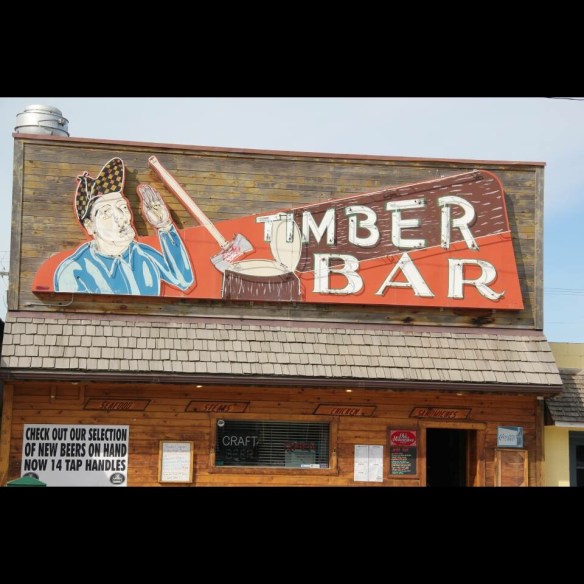

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

The Hell Roaring’ Gulch part of the museum is in stark contrast to the mid-20th century engineered, technological landscape of the Orphan Girl Mine. It interprets the mining camp days of Butte from the late 1860s into the 1880s before the corporations stepped in and reshaped the totality of the copper mining industry and built environment of Butte.

The Hell Roaring’ Gulch part of the museum is in stark contrast to the mid-20th century engineered, technological landscape of the Orphan Girl Mine. It interprets the mining camp days of Butte from the late 1860s into the 1880s before the corporations stepped in and reshaped the totality of the copper mining industry and built environment of Butte.

artifacts and banners shown in this photo); the store, which displays common items sought by the miners and their families; and various offices that show the business of

artifacts and banners shown in this photo); the store, which displays common items sought by the miners and their families; and various offices that show the business of mapping the mines, registering claims, and assaying the metals .

mapping the mines, registering claims, and assaying the metals . In my first post about the World Museum of Mining, I addressed this valuable collection of a historic mine, several historic buildings, and thousands of historic artifacts briefly. Properties like the impressive log construction of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shown below, are invaluable. The World Museum of Mining deserved more attention, and it deserves the attention of any serious heritage tourist to Montana.

In my first post about the World Museum of Mining, I addressed this valuable collection of a historic mine, several historic buildings, and thousands of historic artifacts briefly. Properties like the impressive log construction of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shown below, are invaluable. The World Museum of Mining deserved more attention, and it deserves the attention of any serious heritage tourist to Montana.

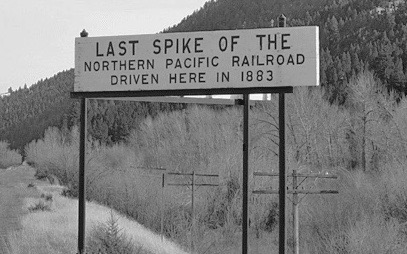

Beaverhead County Montana is huge–in its area it is bigger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined, and is roughly the size of Connecticut. Within these vast boundaries in the southwest corner of Montana, less than 10,000 people live, as counted in the 2010 census. As this blog has previously documented, in a land of such vastness, transportation means a lot–and federal highways and the railroad are crucial corridors to understand the settlement history of Beaverhead County.

Beaverhead County Montana is huge–in its area it is bigger than the states of Rhode Island and Delaware combined, and is roughly the size of Connecticut. Within these vast boundaries in the southwest corner of Montana, less than 10,000 people live, as counted in the 2010 census. As this blog has previously documented, in a land of such vastness, transportation means a lot–and federal highways and the railroad are crucial corridors to understand the settlement history of Beaverhead County. This post takes another look at the roads less traveled in Beaverhead County, such as Blacktail Creek Road in the county’s southern end. The road leads back into lakes and spectacular scenery framed by the Rocky Mountains.

This post takes another look at the roads less traveled in Beaverhead County, such as Blacktail Creek Road in the county’s southern end. The road leads back into lakes and spectacular scenery framed by the Rocky Mountains.

But along the road you find historic buildings left behind as remnants of ranches now lost, or combined into even larger spreads in the hopes of making it all pay some day.

But along the road you find historic buildings left behind as remnants of ranches now lost, or combined into even larger spreads in the hopes of making it all pay some day.

Birch Creek Road was shaped by the efforts of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s as the Corps carried out multiple projects in the national forest. This road has a logical destination–the historic Birch Creek C.C.C. Camp, which has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The University of Montana Western uses the property for outdoor education and as a conference center that is certainly away from everything.

Birch Creek Road was shaped by the efforts of the Civilian Conservation Corps in the 1930s as the Corps carried out multiple projects in the national forest. This road has a logical destination–the historic Birch Creek C.C.C. Camp, which has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The University of Montana Western uses the property for outdoor education and as a conference center that is certainly away from everything.

which once hung in the Richland County Courthouse in Sidney (and now displayed at the Mondak Heritage Center in Sidney) and the numerous murals that graced new post offices and federal buildings across Montana, the one below from Dillon demonstrates

which once hung in the Richland County Courthouse in Sidney (and now displayed at the Mondak Heritage Center in Sidney) and the numerous murals that graced new post offices and federal buildings across Montana, the one below from Dillon demonstrates that the arts program of the 1930s stretched across Montana, from Sidney to Dillon.

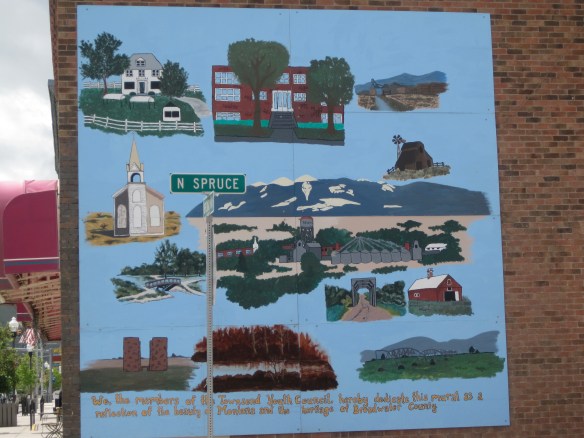

that the arts program of the 1930s stretched across Montana, from Sidney to Dillon. When I lived in Helena in the first half of the 1980s, of course I noticed murals, such as one above on the state’s important women’s history on Last Chance Gulch, which itself had various installations of interpretive sculpture to tell the story of a place that had been so “renewed” as to lose all meaning.

When I lived in Helena in the first half of the 1980s, of course I noticed murals, such as one above on the state’s important women’s history on Last Chance Gulch, which itself had various installations of interpretive sculpture to tell the story of a place that had been so “renewed” as to lose all meaning.

Another northwestern Montana town–the gateway town of Eureka on U.S. Highway 89. uses a mural to set the scene of a quiet, peaceful place no matter the season:

Another northwestern Montana town–the gateway town of Eureka on U.S. Highway 89. uses a mural to set the scene of a quiet, peaceful place no matter the season:

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

Ranchers had taken bits of older buildings from Pioneer and incorporated them into later structures between the mining district and Gold Creek. Pioneer as a ghost town barely existed then and little marks its past except for the scars of mining.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors.

But the most important community institution (yes, the Dinner Bell Restaurant out on the interstate exit is important but it is a new business) is the Gold Creek School, a rather remarkable building in that residents took two standard homestead era one-room schools and connected them by way of a low roof “hyphen” between the front doors. Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

Adaptation and survival–the story of many buildings at Gold Creek and Pioneer. Historical markers are scarce there but the history in the landscape can still be read and explored.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

deteriorating in the mid-1980s but a determined effort to save the building and use it as an anchor for the Montana Avenue historic district has proven to be a great success in the 21st century.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.

Milwaukee Road depot there, since Harlowtown was such an important place in the railroad’s history as an electric line.