Hot Springs, off from Montana Highway 28 on the eastern edge of Sanders County, was a place that received little attention in the survey work of 1984-1985. Everyone knew it was there, and that hot springs had been in operation trying to lure automobile travelers since the 1920s–but at that time, that was too new. The focus was elsewhere, especially on the late 19th century resorts like Chico Hot Springs (believe or not, Chico was not on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984). This section of what is now the reservation of the Consolidated Salish and Kootenai Tribes was opened to homesteaders in 1910 and first settlement came soon thereafter. The development of the hot springs as an attraction began within a generation.

Hot Springs, off from Montana Highway 28 on the eastern edge of Sanders County, was a place that received little attention in the survey work of 1984-1985. Everyone knew it was there, and that hot springs had been in operation trying to lure automobile travelers since the 1920s–but at that time, that was too new. The focus was elsewhere, especially on the late 19th century resorts like Chico Hot Springs (believe or not, Chico was not on the National Register of Historic Places in 1984). This section of what is now the reservation of the Consolidated Salish and Kootenai Tribes was opened to homesteaders in 1910 and first settlement came soon thereafter. The development of the hot springs as an attraction began within a generation.

Due to the 21st century fascination from historic preservationists for the modern movement of the mid-20th century, however, Hot Springs is now squarely on the map as a fascinating example of a tourist destination at the height of the automobile age from the 1930s to 1960s.

Due to the 21st century fascination from historic preservationists for the modern movement of the mid-20th century, however, Hot Springs is now squarely on the map as a fascinating example of a tourist destination at the height of the automobile age from the 1930s to 1960s.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, Symes Hotel and hot springs takes you back to the era of the Great Depression. Fred Symes acquired the family property and opened the Mission-style hotel in 1930. It has changed somewhat over the decades, but not much. The narrow hallways of the baths, with their single tubs ready for a soak, are still in operation.

What the Symes did for Hot Springs was to make it a destination, and to give a vernacular Mission-style look to other buildings from that decade such as the old Mission style building below and other storefronts on the town’s main street.

Not everything fit into this mold, naturally. There remains a representative set of gable-front shotgun-form “cabins” that housed visitors staying for several days and various one-story buildings served both visitors and year-round residents.

Not everything fit into this mold, naturally. There remains a representative set of gable-front shotgun-form “cabins” that housed visitors staying for several days and various one-story buildings served both visitors and year-round residents.

Then a few years after World War II the tribe decided to invest in the town through the creation of the modernist landmark known as the Camas Hot Springs, truly a bit of the International style on the high prairie of western Montana.

From a photo in the lobby of the Symes Hotel.

This venture initially was successful and led to a population boom in the 1950s and 1960s but then as the interstates were built and the 1970s recession impacted travel choices, the Camas struggled and closed c. 1980. For the last 30 years this grand modernist design has been slowly melting away.

The loss would be significant because few mid-20th century buildings in Montana, especially rural Montana, are so expressive of the modernist ethos, with the flat roofs, the long, low wings and the prominent chimney as a design element. Then there are the round steel stilts on which the building rests.

The loss would be significant because few mid-20th century buildings in Montana, especially rural Montana, are so expressive of the modernist ethos, with the flat roofs, the long, low wings and the prominent chimney as a design element. Then there are the round steel stilts on which the building rests.

As this mural suggests, today Hot Springs embraces its deep past as a place of sacred meaning to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai. And it continues to try to find a way to attract visitors as a 21st century, non-traditional hot springs resort.

As this mural suggests, today Hot Springs embraces its deep past as a place of sacred meaning to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai. And it continues to try to find a way to attract visitors as a 21st century, non-traditional hot springs resort.

Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

Plains is the second largest town in Sanders County, noted as the home of the county fairgrounds, the center of the local agricultural economy, and like Thompson Falls a significant place along the Clark’s Fork River and the Montana Highway 200 corridor.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

century feel, be it in institutions, such as the local Grange above, or the continuation of the local VFW hall and bowling alley, below.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana.

The Noxon Dam was finished in 1959. It is a mile in length, 260 feet in height and 700 feet wide at its base. Its generators can power approximately 365,000 homes, making it the second-largest capacity hydroelectric facility in Montana. Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power.

Today visitors can view the dam from various parking areas and short walking trails, one of which passes over the historic line of the Northern Pacific Railroad. The property has interpretive signs about the history of the project as well as about the engineering of hydroelectric power. Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the

Along the banks of the river/reservoir, a much more recent public park has opened–with public sculpture reminding everyone of the Native Americans who once camped along the river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

river at this place. By bringing the deep past of the region in view of the modern, this site is a new favorite place–wherever you are in Montana, and there are many modern engineering marvels–the Indians were always there first, using those same natural resources in far different ways.

On the outskirts of town, the 1920s monument to David Thompson was the centerpiece of the town’s heritage tourism attractions in 1984-1985, now it is more of an afterthought. David Thompson was a Welsh-Canadian who established the first trading post in this river valley, called Saleesh House, for the tribe with whom this veteran of both the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company had targeted for the fur trade. His last visit to Saleesh House came in the winter of 1812. Thompson, I thought in 1984, was a very important figure in Montana history but increasingly a neglected trader–in fact most of the early traders, like those of the American Fur Company on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, are neglected, even though significant places associated with them remain intact on the state’s landscape.

On the outskirts of town, the 1920s monument to David Thompson was the centerpiece of the town’s heritage tourism attractions in 1984-1985, now it is more of an afterthought. David Thompson was a Welsh-Canadian who established the first trading post in this river valley, called Saleesh House, for the tribe with whom this veteran of both the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company had targeted for the fur trade. His last visit to Saleesh House came in the winter of 1812. Thompson, I thought in 1984, was a very important figure in Montana history but increasingly a neglected trader–in fact most of the early traders, like those of the American Fur Company on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, are neglected, even though significant places associated with them remain intact on the state’s landscape. About one hundred years after David Thompson’s last winter at Saleesh House, an entirely different landscape emerged along the Clark’s Fork River, one that introduced the recent technology of electricity to the region. To support and encourage the development of hydroelectric facilities, the city of Thompson Falls combined with investors to build what became known as the “High Bridge,” a way for automobile traffic to cross this gorge in the Clark’s Fork and unite settlement on both sides of the river.

About one hundred years after David Thompson’s last winter at Saleesh House, an entirely different landscape emerged along the Clark’s Fork River, one that introduced the recent technology of electricity to the region. To support and encourage the development of hydroelectric facilities, the city of Thompson Falls combined with investors to build what became known as the “High Bridge,” a way for automobile traffic to cross this gorge in the Clark’s Fork and unite settlement on both sides of the river. The High Bridge was an early 20th century Montana engineering marvel. It was 588 feet in length, designed for automobile traffic, with a 18-feet wide deck standing on a combination of Pratt and Parker trusses. It is the longest bridge of its kind in Montana.

The High Bridge was an early 20th century Montana engineering marvel. It was 588 feet in length, designed for automobile traffic, with a 18-feet wide deck standing on a combination of Pratt and Parker trusses. It is the longest bridge of its kind in Montana.

But within two years, residents and officials combined together to place the bridges and hydroelectric facilities in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. They were preserved, but still not used, for a generation.

But within two years, residents and officials combined together to place the bridges and hydroelectric facilities in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. They were preserved, but still not used, for a generation. In 2009-2010, residents worked with local, state, and federal government officials to restore the bridge, add a pedestrian deck, and to open the bridge and either side of the bridge as a public park. Funding in part came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, one of the ways that short-lived federal building effort benefited historic preservation in Montana small towns.

In 2009-2010, residents worked with local, state, and federal government officials to restore the bridge, add a pedestrian deck, and to open the bridge and either side of the bridge as a public park. Funding in part came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, one of the ways that short-lived federal building effort benefited historic preservation in Montana small towns. The High Bridge experience not only reconnected Thompson Falls to its river roots, it also creates an unique experience for heritage travelers. The site is not that far different from 100 years ago, giving you the chance to cross a river and peer below but also to realize just how “wild” automobile traffic was in the 1910s and 1920s.

The High Bridge experience not only reconnected Thompson Falls to its river roots, it also creates an unique experience for heritage travelers. The site is not that far different from 100 years ago, giving you the chance to cross a river and peer below but also to realize just how “wild” automobile traffic was in the 1910s and 1920s. In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core. The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century. Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks.

Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks. But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls. The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28.

The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28. Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly,

Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly, a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast.

a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast. In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century.

In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century. Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

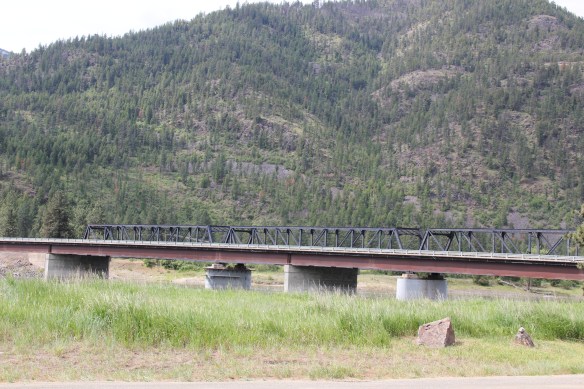

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed. Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

of the Milwaukee Road in 1980, the town has steadily lost population-2oo less residents in 2015 compared to my first visit 30 years earlier. Never a large place–the town’s top population was 1242 residents in 1960–Superior has several landmark buildings from its railroad days but only one has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

of the Milwaukee Road in 1980, the town has steadily lost population-2oo less residents in 2015 compared to my first visit 30 years earlier. Never a large place–the town’s top population was 1242 residents in 1960–Superior has several landmark buildings from its railroad days but only one has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. That one place, the Superior School, is spectacular and its tall central tower has long served as a community beacon. Built 1915-16 by contractor Charles Augustine, the high school reflected Colonial Revival style, and later community growth led to wing additions in 1925, shown above, and in 1947.

That one place, the Superior School, is spectacular and its tall central tower has long served as a community beacon. Built 1915-16 by contractor Charles Augustine, the high school reflected Colonial Revival style, and later community growth led to wing additions in 1925, shown above, and in 1947. Another Colonial Revival-styled public building is the Mineral County Courthouse, 1920, complete with its colonial-inspired cupola. Mineral County was created in 1914. This building is more complete rural interpretation of Colonial Revival style than the school.

Another Colonial Revival-styled public building is the Mineral County Courthouse, 1920, complete with its colonial-inspired cupola. Mineral County was created in 1914. This building is more complete rural interpretation of Colonial Revival style than the school.

The historic Strand Theater (c. 1915) operated in 1984 but closed in 2013 and remained shuttered when I visited in 2015, no doubt a victim of not only the home theatre phenomenon but also the switch to digital delivery of movies in this decade. This theatre, however, is a rare and important building from the homesteading era of the 1910s.

The historic Strand Theater (c. 1915) operated in 1984 but closed in 2013 and remained shuttered when I visited in 2015, no doubt a victim of not only the home theatre phenomenon but also the switch to digital delivery of movies in this decade. This theatre, however, is a rare and important building from the homesteading era of the 1910s. From the same decade, the historic Masonic Mountain Lodge still operates, serving as another community outlet and center in Superior. The town’s population height in the 1960s led to the construction of the institutional Ranch-style of the Superior High School, one of two bits of mid-century modernism in Superior.

From the same decade, the historic Masonic Mountain Lodge still operates, serving as another community outlet and center in Superior. The town’s population height in the 1960s led to the construction of the institutional Ranch-style of the Superior High School, one of two bits of mid-century modernism in Superior.

The other example dates to 1958 and represents yet another example of modern design in a rural Catholic Church in Montana. St Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Church is also a

The other example dates to 1958 and represents yet another example of modern design in a rural Catholic Church in Montana. St Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Church is also a Ranch-styled inspired design, although its stand-alone but visually and physically linked low bell tower is unique compared to other Montana Catholic churches from this era.

Ranch-styled inspired design, although its stand-alone but visually and physically linked low bell tower is unique compared to other Montana Catholic churches from this era. The church is Superior’s best contribution to Montana modernism and complements well the Victorian influence found at the town’s historic United Methodist Church, built almost 50 years earlier. Note that both churches have low bell towers.

The church is Superior’s best contribution to Montana modernism and complements well the Victorian influence found at the town’s historic United Methodist Church, built almost 50 years earlier. Note that both churches have low bell towers.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road. The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

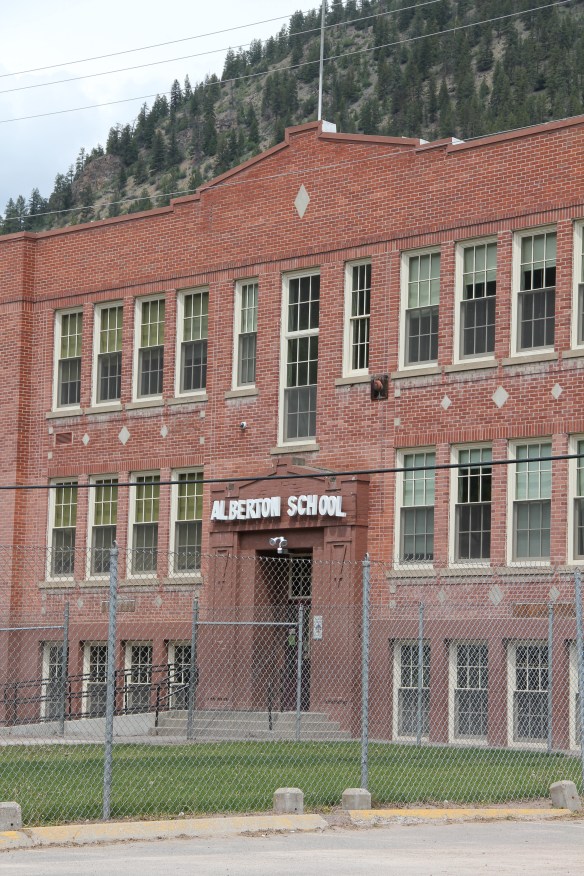

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work.

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism.

I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism. The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings. The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

Downtown Missoula’s architectural wonders make it a distinctive urban Western place. Let’s start with my favorite, the striking Art Moderne styled Florence Hotel (1941) designed by architect G.A. Pehrson. Located between the two railroad depots on Higgins Street, the hotel served tourists and residents as a symbol of the town’s classy arrival on the scene–it was the first place with air-conditioning–of a region transforming in the 1940s and 1950s.

Downtown Missoula’s architectural wonders make it a distinctive urban Western place. Let’s start with my favorite, the striking Art Moderne styled Florence Hotel (1941) designed by architect G.A. Pehrson. Located between the two railroad depots on Higgins Street, the hotel served tourists and residents as a symbol of the town’s classy arrival on the scene–it was the first place with air-conditioning–of a region transforming in the 1940s and 1950s. With the coming of the interstate highway in the 1970s, tourist traffic declined along Higgins Street and the Florence Hotel was turned into offices and shops, a function that it still serves today.

With the coming of the interstate highway in the 1970s, tourist traffic declined along Higgins Street and the Florence Hotel was turned into offices and shops, a function that it still serves today. Next door is another urban marvel, the Wilma Theatre, which dates to 1921 and like the Florence it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The building was the city’s first great entertainment landmark (even had an indoor swimming pool at one time) but with offices and other business included in this building that anchored the corner where Higgins Street met the Clark’s Fork River. Architects Ole Bakke and H. E. Kirkemo designed the theatre in the fashionable Renaissance Revival style, with a hint towards the “tall buildings” form popularized by architect Louis Sullivan, the building later received an Art Deco update, especially with the use of glass block in the ticket booth and the thin layer of marble highlighting the entrance.

Next door is another urban marvel, the Wilma Theatre, which dates to 1921 and like the Florence it is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The building was the city’s first great entertainment landmark (even had an indoor swimming pool at one time) but with offices and other business included in this building that anchored the corner where Higgins Street met the Clark’s Fork River. Architects Ole Bakke and H. E. Kirkemo designed the theatre in the fashionable Renaissance Revival style, with a hint towards the “tall buildings” form popularized by architect Louis Sullivan, the building later received an Art Deco update, especially with the use of glass block in the ticket booth and the thin layer of marble highlighting the entrance.

Missoula’s first major department store and entrepreneurial center. The late Victorian era architectural styling of the two-story building also set a standard for many other downtown businesses from 1890 to 1920. These can be categorized as two-part commercial fronts, with the first floor serving as the primary commercial space and the second floor could be offices, dwelling space for the owner, or most common today storage space.

Missoula’s first major department store and entrepreneurial center. The late Victorian era architectural styling of the two-story building also set a standard for many other downtown businesses from 1890 to 1920. These can be categorized as two-part commercial fronts, with the first floor serving as the primary commercial space and the second floor could be offices, dwelling space for the owner, or most common today storage space.

Gibson, the building is one of the state’s best examples of what is called “Beaux Arts classicism,” a movement in the west so influenced by the late 1890s Minnesota State Capitol by architect Cass Gilbert.

Gibson, the building is one of the state’s best examples of what is called “Beaux Arts classicism,” a movement in the west so influenced by the late 1890s Minnesota State Capitol by architect Cass Gilbert.

Just as impressive, but in a more Renaissance Revival style, is the Elks Lodge (1911), another building that documents the importance of the city’s working and middle class fraternal lodges in the early 20th century.

Just as impressive, but in a more Renaissance Revival style, is the Elks Lodge (1911), another building that documents the importance of the city’s working and middle class fraternal lodges in the early 20th century.

Of more recent construction is another federal courthouse, the modernist-styled Russell Smith Federal Courthouse, which was originally constructed as a bank. In 2012, another judicial chamber was installed on the third floor. Although far removed from the classic

Of more recent construction is another federal courthouse, the modernist-styled Russell Smith Federal Courthouse, which was originally constructed as a bank. In 2012, another judicial chamber was installed on the third floor. Although far removed from the classic look, the Russell Smith Courthouse is not out-of-place in downtown Missoula. There are several other buildings reflecting different degrees of American modern design, from the Firestone building from the 1920s (almost forgotten today now that is overwhelmed by its neighbor the Interstate Bank Building) to the standardized designed of gas stations of

look, the Russell Smith Courthouse is not out-of-place in downtown Missoula. There are several other buildings reflecting different degrees of American modern design, from the Firestone building from the 1920s (almost forgotten today now that is overwhelmed by its neighbor the Interstate Bank Building) to the standardized designed of gas stations of 1930s and 1940s, complete with enamel panels and double garage bays, standing next to the Labor Temple.

1930s and 1940s, complete with enamel panels and double garage bays, standing next to the Labor Temple. Modernism is alive and well in 21st century Missoula, with a office tower at St. Patrick’s Hospital, a new city parking garage, and the splashy Interstate Bank building, which overwhelms the scale of the adjacent Missoula Mercantile building–which had been THE place for commerce over 100 years earlier.

Modernism is alive and well in 21st century Missoula, with a office tower at St. Patrick’s Hospital, a new city parking garage, and the splashy Interstate Bank building, which overwhelms the scale of the adjacent Missoula Mercantile building–which had been THE place for commerce over 100 years earlier.