Monida, at the Idaho-Montana border, on Interstate I-15.

Country towns of Beaverhead County–wait, you cry out: isn’t every town in Beaverhead County a country town? Well yes, since Dillon, the county seat, has a single stop light, you can say that. But Dillon is very much an urban oasis compared to the county’s tiny villages and towns scattered all about Beaverhead’s 5,572 square miles, making it the largest county in Montana.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

The next town north on the corridor created by the railroad/highway/interstate is Lima,  which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

Lima is a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, the plan favored by the engineers of the Utah and Northern as the railroad moved into Montana. The west side of the tracks, where the two-lane U.S. Highway 91 passed, was the primary commercial district, with several brick and frame two-story buildings ranging from the 1880s to the 1910s.

The east side, opposite old U.S. Highway 91, was a secondary area; the Lima Historical Society is trying to keep an old 1880s building intact for the 21st century.

The town’s comparative vitality is shown by its metal Butler Building-like municipal building, and historic churches, ranging from a early 20th century shingle style to a 1960s contemporary style Gothic church of the Latter Day Saints.

The town’s pride naturally is its school, which developed from the early 20th century two-story brick schoolhouse to become the town’s center of community.

Eight miles to the north is a very different historic schoolhouse, the one-story brick Dell school (1903), which had been converted into a wonderful cafe when I stopped in 1984. It is still a great place–if you don’t stop here for pie or a caramel roll (or both), you goofed.

The Calf-A is not the only place worth a look at Dell, a tiny railroad town along the historic Utah and Northern line, with the Tendroy Mountains in the background. Dell still has its

post office, within its one store, its community hall, and a good steakhouse dive, the false-front Stockyard Inn. But most importantly, for an understanding of the impact of World

War II on Montana, Dell has an air-strip, which still contains its 1940s B-17 Radar base, complete with storehouse–marked by the orange band around the building–and radar tower. Kate Hampton of the Montana State Historic Preservation Office in 2012 told me to be of the lookout for these properties. Once found throughout Montana, and part of the guidance system sending planes northward, many have disappeared over the years. Let’s hope the installation at Dell remains for sometime to come.

There are no more towns between Dell and Dillon but about halfway there is the Clark Canyon Reservoir, part of the reshaping of the northwest landscape by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in the 1960s. The bureau in 1961-1964 built the earthen dam and created the

reservoir, which inundated the small railroad town of Armstead, and led to the re-routing of U.S. Highway 91 (now incorporated into the interstate at this point).

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

effort to mark and interpret the site came from the Daughters of the American Revolution, who not surprisingly focused on the Sacajawea story. Reclamation officials added other markers after the construction of the dam and reservoir.

In this century the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail has added yet another layer of public interpretation in its attempt to tell the whole story of the expedition and its complicated relations with the Native Americans of the region.

North of Dillon along the old route of U.S. Highway 91 and overlooking the corridor of the Utah and Northern Railroad is another significant Lewis and Clark site, known as Clark’s Lookout, which was opened to the public during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial of the early 21st century.

The lookout is one of the exciting historic sites that have been established in Montana in the 30 years since my initial survey for the state historic preservation plan. Not only does the property interpret an important moment in the expedition’s history–from this vantage point William Clark tried to understand the countryside before him and the best direction to take–it also allows visitors to literally walk in his footsteps and imagine the same perspective.

Of course what Clark viewed, and what you might see, are vastly different–the tracks of the Utah and Northern, then route of old U.S. 91 are right up front, while the town of Dillon creeps northward toward the lookout.

Our last stop for part one of Beaverhead’s country towns is Glen, a village best accessed by old U. S. Highway 91. A tiny post office marks the old town. Not far away are two historic

North of Glen you cross the river along old U.S. Highway 91 and encounter a great steel tress bridge, a reminder of the nature of travel along the federal highways of the mid-20th century.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town. How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history.

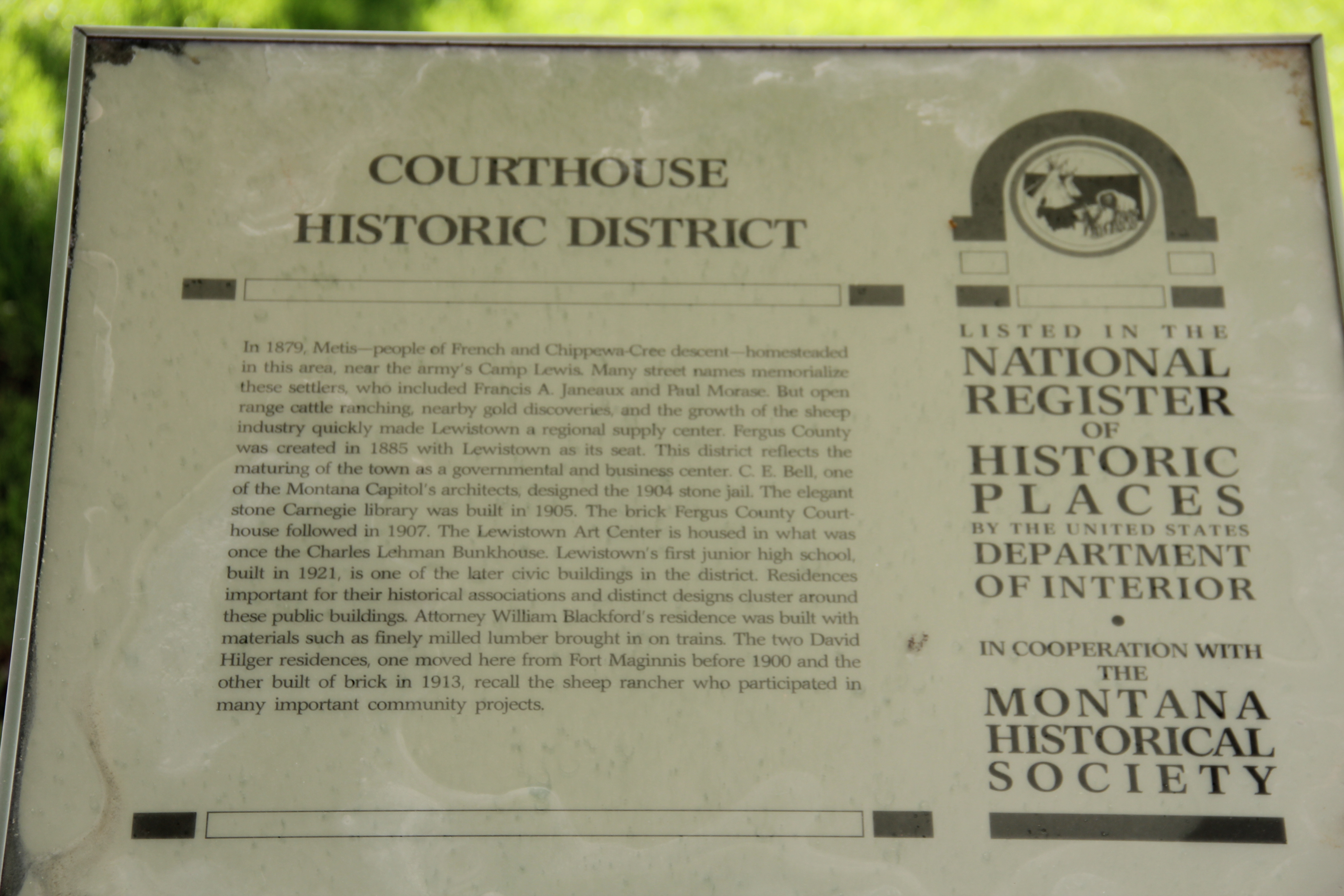

How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history. Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society.

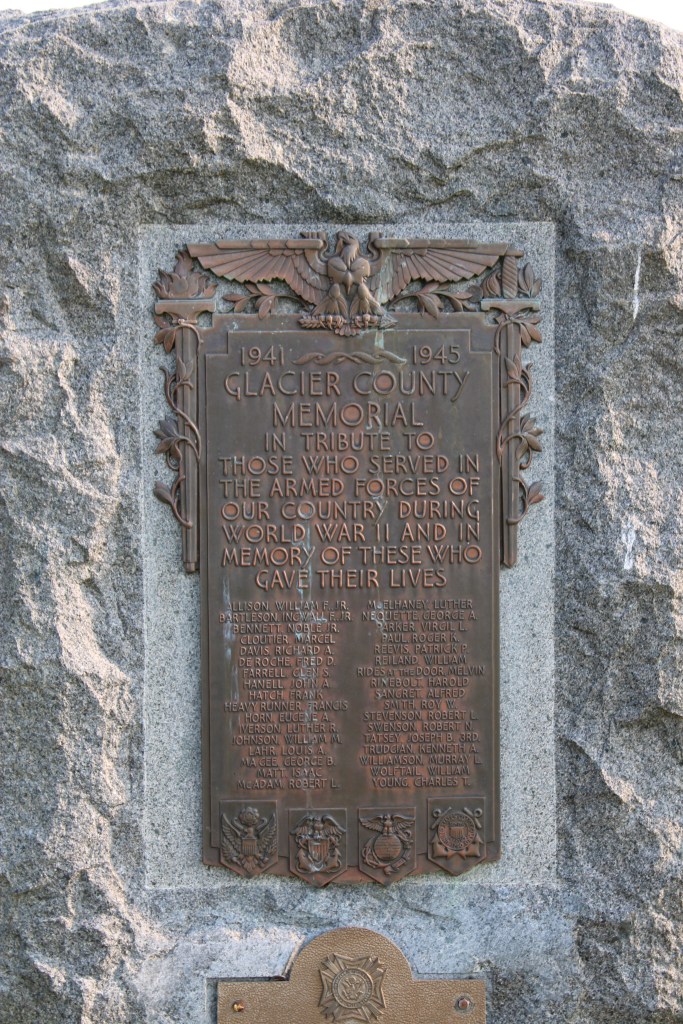

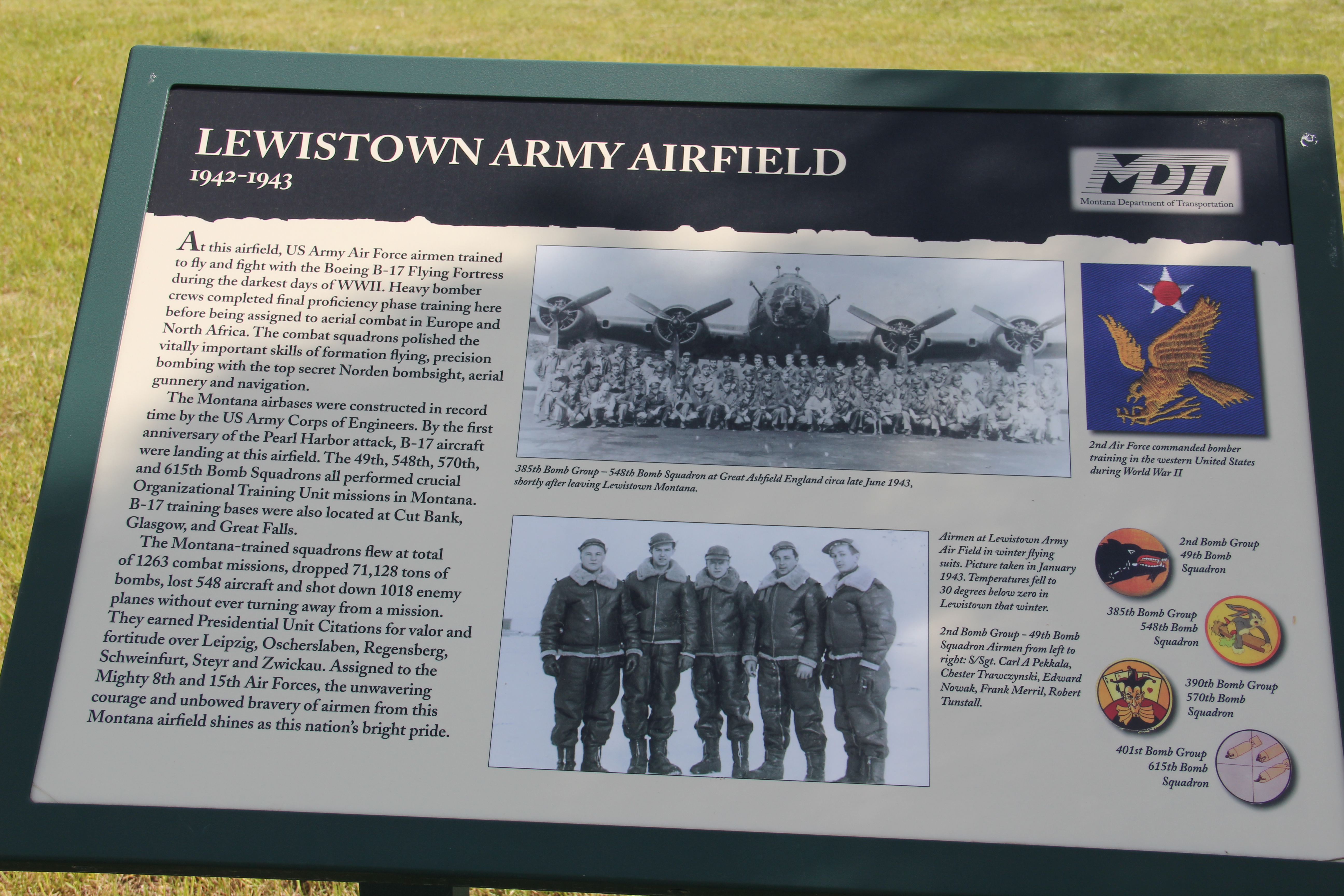

Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society. What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense.

What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense. Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation.

Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation. Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods. The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and

The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today.

residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today. As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis.

As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis. Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.