Riverside Cemetery dates to 1883, a time of considerable change and expansion in Fort Benton’s history. Just 2 years earlier, summer 1881, the U.S. Army left the fort, and it began a rapid decline. In the following winter of 1881-1882 the town began a building boom that led to the construction of the Grand Union Hotel by the end of 1882.

Freight traffic on the Missouri River also boomed and the River Press, the city’s leading newspaper for the next 100 plus years, published its first edition. 1882 also witnessed the city’s first electric lights and the construction of many new residences. And by the year resident had formed the Riverside Cemetery Association.

The loss of the Chouteau County Courthouse to fire in early 1883 didn’t seem to slow momentum at all. That spring voters incorporated Fort Benton—what had been a trading and military town was now a formally established town. Soon thereafter Riverside Cemetery was established on the Missouri River bluffs northeast of town.

The new town cemetery had approximately 40 fenced acres and was ready for use by Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day) in 1883. The cemetery also had reinterred graves from earlier in-town cemeteries at approximately the location of First Christian Church and behind Haas and Associates and Farmers Union Oil Company.

Today the gap between the initial cemetery and burials in the 20th century is noticeable. The early burials are on the east side while the modern section is on the east side clustered near a row of trees m. Clearly early tombstones have been lost—the number of grave depressions indicate that there are many additional burials that lack a grave marker.

The remaining grave markers from the late 19th century tell powerful stories. The Charles Fish (d. 1890) obelisk with urn marker below honored a Canadian native who served as a drummer boy with the 38th Wisconsin Infantry in the Civil War; he was only 15 years old when he joined.

Tombstones with cross themes mark the graves of Jane Jackson (d. 1885) and Edward Kelly (d. 1890).

In 1891 the cemetery received its first U.S. military veterans markers. The one below was for Patrik (the spelling used on the tombstone) Fallon, a Civil War veteran. By now Fort Benton had grown to the point that its Decoration Day ceremony involved hundreds, led by the cemetery association, camps of the Grand Army of the Republic and soldiers from Fort Assiniboine.

While the graves of many pioneers are unmarked, the Sullivan family located its graves near the edge of the bluff, truly an awe-inspiring setting overlooking the town, river, and railroad tracks.

Impressive tombstone art is scattered throughout the cemetery. The unique yet beautiful pressed metal crosses for brothers Julius (d. 1923) and Henry (d. 1924) Bogner belong, stylistically to the Victorian era, but were commissioned and installed in the Jazz Age.

Riverside Cemetery has an impressive veterans section, known as the Military Plot. Veterans from the Spanish American War of the 1890s to the conflicts of the 21st century are buried here.

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years. The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies. I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

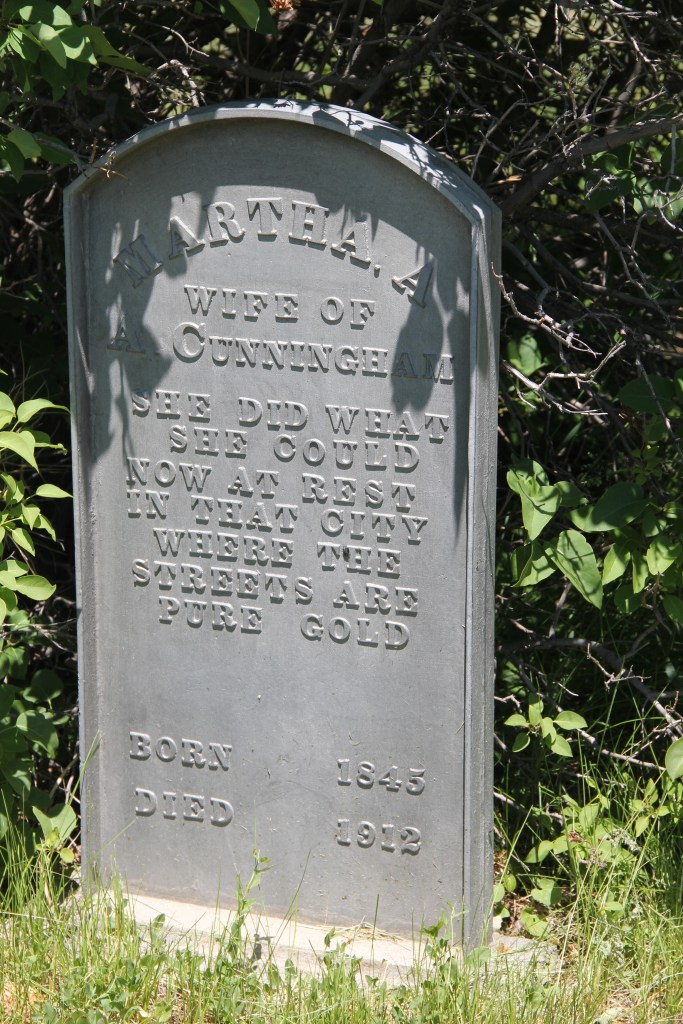

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.