My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

The road into Bannack passes through sparsely populated country, and you wonder what the miners, and then the families, who passed this way thought as they approached the town by foot or by horse, if they were lucky. The “road” then of course was not more than

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

Fairweather Inn in Virginia City.

The old Goodrich Hotel is not the only thing that Virginia City got from Bannack. Bannack was the first territorial capital of Montana, but then in early 1865 the territorial offices moved to Virginia City. Bannack’s boom had already started to decline, and the boom seemed never ending to the east in Madison County.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Ever since the state has repaired buildings and structures as necessary but decided long ago to preserve the town as a ghost town–last residents outside of park rangers left in the 1970s–and not to “restore” it like a Colonial Williamsburg treatment. Thus, it is very

much a rough, open experience for visitors at the town. Doors are open, nooks and crannies can be explored. Public interpretation, outside of the small visitor center, is scant, although more than what I found in 1984, as this back room of old interpretive markers reminded me.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

Bannack is one of the great rural cemeteries in Montana. Don’t make my mistake from 1984–stop here and explore.

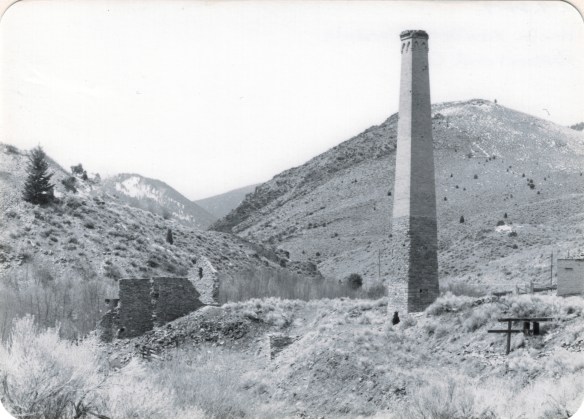

At Farlin, the scars of mining are everywhere, surrounded by sage grass, brush, and scattered trees, trying to recover in what was once a denuded landscape. Operations had ended by the time of the Great Depression. While never a huge place–population estimates top out at 500–Farlin is representative of the smaller mining operations that reshaped the rural western Montana landscape. Not every place became a Butte, or a Virginia City. Properties like Farlin help to tell us of the often lonely and exceedingly difficult search for opportunity in the Treasure State over 100 years ago.

At Farlin, the scars of mining are everywhere, surrounded by sage grass, brush, and scattered trees, trying to recover in what was once a denuded landscape. Operations had ended by the time of the Great Depression. While never a huge place–population estimates top out at 500–Farlin is representative of the smaller mining operations that reshaped the rural western Montana landscape. Not every place became a Butte, or a Virginia City. Properties like Farlin help to tell us of the often lonely and exceedingly difficult search for opportunity in the Treasure State over 100 years ago.

When I returned to Glendale in 2012, I made sure to take a replica shot of the place I had photographed almost 30 years earlier. But I also went father and did my best to document a mining landscape in danger of disappearing in the 21st century. Below is an image when the Hecla smelter was in full production.

When I returned to Glendale in 2012, I made sure to take a replica shot of the place I had photographed almost 30 years earlier. But I also went father and did my best to document a mining landscape in danger of disappearing in the 21st century. Below is an image when the Hecla smelter was in full production. There are some intact buildings at Glendale, but also numerous parts of buildings, facades and foundations that convey how busy the Glendale Road was some 100 years ago.

There are some intact buildings at Glendale, but also numerous parts of buildings, facades and foundations that convey how busy the Glendale Road was some 100 years ago.

Hecla Mining Company operated 28 kilns at a site a few miles away. Within the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge National Forest, the Canyon Creek Kilns are a remarkable property, preserved and now interpreted through the efforts of the U.S. Forest Service. The Forest Service should be commended for this effort. As the images below suggest, this property is one of the best places in Montana to stop and think of the mining landscape of the turn of the twentieth century and imagine what a moonscape it would have been 100 years ago when the kilns consumed all of the surrounding timber.

Hecla Mining Company operated 28 kilns at a site a few miles away. Within the Beaverhead-Deer Lodge National Forest, the Canyon Creek Kilns are a remarkable property, preserved and now interpreted through the efforts of the U.S. Forest Service. The Forest Service should be commended for this effort. As the images below suggest, this property is one of the best places in Montana to stop and think of the mining landscape of the turn of the twentieth century and imagine what a moonscape it would have been 100 years ago when the kilns consumed all of the surrounding timber.

The Big Hole Valley was a place of interest to me in 1984, noted by the image above, for how ranches used logs to build the physical infrastructure–the log snake fences, the gates, the log barns and other ranch structures–of their properties.

The Big Hole Valley was a place of interest to me in 1984, noted by the image above, for how ranches used logs to build the physical infrastructure–the log snake fences, the gates, the log barns and other ranch structures–of their properties.

What I didn’t give as much attention to, already commented on in this blog at numerous places, are the irrigation ditches, a more consistent supply of water that allowed ranchers to expand production.

What I didn’t give as much attention to, already commented on in this blog at numerous places, are the irrigation ditches, a more consistent supply of water that allowed ranchers to expand production.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

Beaverhead County, named for the prominent, ancient landmark on the Beaverhead River at the corner of Madison and Beaverhead county, was the first rural place I visited in Montana after my arrival in Helena in 1981. Why? No pressing reason, except that the place name of Wisdom called out to me.

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club

The town’s large community hall remains in constant use. The separate Women’s Club building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse.

building once welcomed ranch wives and daughters to town, giving them a place to rest and providing a small library of books. It has been converted into a small lodge for skiers and hunters–a great small town example of adaptive reuse. Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop.

Of course the major landmark for travelers through Wisdom in the late 20th century was Conover’s Trading Post, a two-story false front building–clearly the most photographed place in town, and inside a classic western gun and recreation shop. But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.

But the Conover’s facade, even the name, is no more. Not long after my 2012 visit to Wisdom, new owners totally remade the building and business, opening a new store named Hook and Horn.