Montana Highway 200 follows the Blackfoot River as it enters Missoula County from the east. At first you think here is another rural mountain county in Montana, one still defined by community schools like the turn of the century one at Potomac above, and by community halls like the Potomac/Greenough Hall, which also serves as the local Grange meeting place.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

It is a land watered by the river, framed by the mountains, and famous for its beef–which they even brag about at the crossroads of Montana Highways 200 and 83.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

But soon after passing the junction, you enter a much different landscape, particularly at the point where the Blackfoot River meets the Clark’s Fork River. This is an industrial world, defined by the company town design of Bonner and the active transportation crossroads at Milltown. Suddenly you shift from an agricultural landscape into the timber industry, which has long played a major role in the history of Missoula and northwest Montana.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

In 1881 the Northern Pacific Railroad was approaching the river confluence. It contracted with a company led by E. L. Bonner, Andrew Hammond, and Richard Eddy to supply everything the railroad needed but steel as it passed through the region. Two years later the railroad provided the capital for Bonner, Hammond, Eddy, and M.J. Connell to establish the Montana Improvement Company. In c. 1886 the improvement company dammed the rivers and built a permanent sawmill–the largest in the northern Rockies, and created the town of Bonner. The sawmill works and town would later become the Blackfoot Milling and Manufacturing Company and eventually by the late 1890s it was under the control of Marcus Daly and his Anaconda Copper Company. Anaconda ran Bonner as a company town until the 1970s.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Although buildings have been lost in the last 30 years, especially at the sawmill complex which had a disastrous fire in 2008 and a heavy snow damaged another historic structure in 2011, I found Bonner in 2014 to remain a captivating place, and one of the best extant company towns left in Montana.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

Montana Highway 200 passes through the heart of Bonner while Interstate I-90 took a good bit of Milltown when it was constructed in the 1970s. Both Bonner and Milltown are heavily influenced by transportation and bridges needed to cross the Blackfoot and Clark’s Fork rivers.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The Milltown Bridge has been restored as a pedestrian walkway over the Blackfoot River. It is the best place to survey the Blackfoot Valley and the old sawmill complex.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The pedestrian bridge and heritage trail serve as a focal point for public interpretation, for the Lewis and Clark Expedition, the Mullan Road, and then the lumber industry, which all passed this way over time, a conjunction of rivers and history that lie at the heart of the local and state (Milltown State Park) effort to interpret this important place.

The industrial company town of Bonner is a fascinating place to visit. On the south side side is company housing, a company store (now a museum and post office), and then other community institutions such as the Bonner School, St. Ann’s Catholic Church, and Lutheran Church.

Bonner Museum and Post Office

St. Ann’s Catholic Church, Bonner.

Our Savior Lutheran Church, Bonner.

The north side of Montana 200 has a rich array of standardized designed industrial houses, ranging from unadorned cottages to large bungalows for company administrators, all set within a landscape canopy of large trees and open green space. The mill closed in the first decade of the 21st century but the town remains and the condition of both dwellings and green space is ample testimony to the pride of place still found in Bonner.

Milltown is not as intact as Bonner. One major change came in 1907-1908 when the Milwaukee Road built through here and then in the 1920s came U.S. Highway 10. A huge swath of Milltown was cut away when Interstate highway I-90 was built 50 years later, and once the mill closed, the remaining commercial buildings have fought to remain in business, except for that that cater to travelers at the interstate exit.

One surviving institution is Harold’s Club, which stands on the opposite side of the railroad tracks. Here is your classic early 20th century roadhouse, where you could “dine, drink, and dance” the night away after a hard day at the mills.

The closing of the mills changed life in Bonner and Milltown but it did not end it. Far from it. I found the residents proud of their past and determined to build a future out of a landscape marked by failed dams, fires, corporate abandonment, and shifting global markets.

Montana Highway 1, designated the Pintler Scenic Route, has long been one of my favorite roads. It was the first Montana road to be paved in its entirety. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, I documented the route as U.S. 10A, but once government officials decided to decommission the U.S. 10 designation in 1986, the name U.S. 10A also went away. t. In its early decades the route had passed through Opportunity to Anonconda onto Phillipsburg and then Drummond, but for all of my time in Montana, the highway has gone from Interstate I-90, Anaconda/Opportunity exit to the west and then north to the Drummond exit on the same interstate. There is a new 21st century rest stop center at the Anaconda I-90 exit that has a Montana Department of Transportation marker about the mountain ranges and the Pintler route.

Montana Highway 1, designated the Pintler Scenic Route, has long been one of my favorite roads. It was the first Montana road to be paved in its entirety. During the state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, I documented the route as U.S. 10A, but once government officials decided to decommission the U.S. 10 designation in 1986, the name U.S. 10A also went away. t. In its early decades the route had passed through Opportunity to Anonconda onto Phillipsburg and then Drummond, but for all of my time in Montana, the highway has gone from Interstate I-90, Anaconda/Opportunity exit to the west and then north to the Drummond exit on the same interstate. There is a new 21st century rest stop center at the Anaconda I-90 exit that has a Montana Department of Transportation marker about the mountain ranges and the Pintler route.

The town of Opportunity was not a priority for my travels in 1984-1985 but recent scholarship on how local residents have fought back against the decades of pollution from Anaconda’s Washoe Stack led me to give this small town of 500 a new look. The book is Brad Tyer’s Opportunity, Montana: Big Copper, Bad Water, and the Burial of an American Landscape (2014). Tyler details how the success of Anaconda also meant the sacrifice of thousands of surrounding acres to the pollution belching daily from the Washoe Stack until it closed in 1981. He then reviews in detail how in the 21st century, EPA heaped a new disaster on the town by moving Milltown wastes from the Clark’s Fork River near Missoula to Opportunity, telling locals that the Milltown soil would be new top soil for Opportunity. The environmental solution didn’t work, leaving the town in worse shape than before.

The town of Opportunity was not a priority for my travels in 1984-1985 but recent scholarship on how local residents have fought back against the decades of pollution from Anaconda’s Washoe Stack led me to give this small town of 500 a new look. The book is Brad Tyer’s Opportunity, Montana: Big Copper, Bad Water, and the Burial of an American Landscape (2014). Tyler details how the success of Anaconda also meant the sacrifice of thousands of surrounding acres to the pollution belching daily from the Washoe Stack until it closed in 1981. He then reviews in detail how in the 21st century, EPA heaped a new disaster on the town by moving Milltown wastes from the Clark’s Fork River near Missoula to Opportunity, telling locals that the Milltown soil would be new top soil for Opportunity. The environmental solution didn’t work, leaving the town in worse shape than before. Opportunity residents got a small fraction of SuperFund monies for the environmental cleanup in the form of Beaver Creek park. But the centerpiece of the park, the Opportunity School built for residents in 1914 by the Anaconda Company, has been mothballed for now. It operated from 1914 until the smelter ceased operations in 1981 and

Opportunity residents got a small fraction of SuperFund monies for the environmental cleanup in the form of Beaver Creek park. But the centerpiece of the park, the Opportunity School built for residents in 1914 by the Anaconda Company, has been mothballed for now. It operated from 1914 until the smelter ceased operations in 1981 and served as the community’s focal point. Restoration of the school is problematic due to the prior use of asbestos, meaning the federally funded park is only partially finished since the SuperFund support is now gone.

served as the community’s focal point. Restoration of the school is problematic due to the prior use of asbestos, meaning the federally funded park is only partially finished since the SuperFund support is now gone.

Sitting at 6,425 feet in elevation Georgetown Lake covers over 3700 acres. Today it is very much a recreational landscape but when it was created in 1885 its job was to generate electrical power for the nearby mines since it stood roughly equal distance between

Sitting at 6,425 feet in elevation Georgetown Lake covers over 3700 acres. Today it is very much a recreational landscape but when it was created in 1885 its job was to generate electrical power for the nearby mines since it stood roughly equal distance between

As the state highway historical marker above documents, this high country area was another mining region. With an vantage point above the lake, Southern Cross is a significant remnant of the mining activities from the early 20th century. The mines here

As the state highway historical marker above documents, this high country area was another mining region. With an vantage point above the lake, Southern Cross is a significant remnant of the mining activities from the early 20th century. The mines here began operation in the mid-1860s and production continued for until World War II. The settlement was largely Finnish and Swedish in the early 20th century when most of the remaining buildings were constructed.

began operation in the mid-1860s and production continued for until World War II. The settlement was largely Finnish and Swedish in the early 20th century when most of the remaining buildings were constructed.

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation.

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation. There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible.

There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible. I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

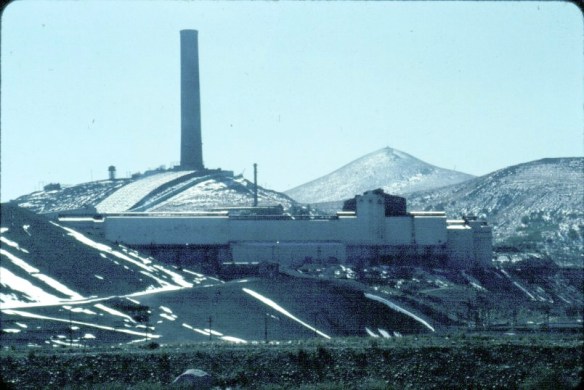

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth. The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of

The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt