Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

A photo of the asylum from 2007

years later. The architect was John C. Paulsen, who then served as the State Architect. The building represents an early effort by the state to provide for its citizens, and the presence of the institution in Boulder shaped that town’s history for the next 120 years.

Boulder is a place of impressive public buildings. The Jefferson County Courthouse (1888-89) is another piece of Victorian architecture, in the Dichardsonian Romanesque style, again by John K. Paulsen. It was listed in the National Register in 1980.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Indeed the importance of schools to not only the state’s history of education but the mere survival of communities has been pinpointed by various state preservation groups and the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Jefferson County still has many significant surviving school buildings from the early 20th century, none of which have been listed yet in the National Register.

Carter School, 1916, Montana City

Clancy School, now the Jefferson County Museum

Basin school, still in use

Caldwell school, one of the few buildings left in this old railroad town

Whitehall still has its impressive Gothic style gymnasium from the 1920s while the school itself shows how this part of the county has gained in population since 1985.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Irrigation and sugar beet cultivation are key 20th century agricultural themes, typically associated with eastern and central Montana. Jefferson County tells that story too, in a different way, at Whitehall. The irrigation ditches are everywhere and the tall concrete stack of the sugar refinery plant still looms over the town.

In 1917 Amalgamated Sugar Company, based in Utah, formed the Jefferson Valley Sugar Company and began to construct but did not finish a refinery at Whitehall. The venture did not begin well, and the works were later sold to the Utah-Idaho Sugar Company in 1920, which never finished the plant but left the stack standing. Nearby is Sugar Beet

Row, where hipped roof duplex residences typical of c. 1920 company towns are still lined up, and in use, although their exteriors have changed over the decades.

Through many posts in this blog, I have identified those informal yet very important community centers found in urban neighborhoods and rural outposts across the state–bars and taverns. Jefferson County has plenty of famous classic watering holes, such as Ting’s Bar in Jefferson City, the Windsor Bar in Boulder, or the Two Bit Bar in Whitehall, not forgetting Roper Lanes and Lounge in Whitehall.

Speaking of recreation, Jefferson County also has one of my favorite hot springs in all of the west, the Boulder Hot Springs along Montana Highway 69. Here is a classic oasis of the early 20th century, complete in Spanish Revival style, and listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Its rough worn exterior only hints at the marvel of its pool and experience of this place.

Mining always has been part of Jefferson County’s livelihood with still active mines near Whitehall and at Wickes. The county also has significant early remnants of the state’s

The coke ovens above are from Wickes (L) and Alhambra (R) while the image directly above is of 21st century mining continuing at Wickes.

mining era, with still extant (but still threatened as well) charcoal kilns at Wickes (1881) and at Alhambra. Naturally with the mining came railroads early to Jefferson County. As you travel Interstate I-15 between Butte and Helena, you are generally following the route of the Montana Central, which connected the mines in Butte to the smelter in Great Falls, and a part of the abandoned roadbed can still be followed.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Corbin concentrator site, 1984

The Northern Pacific Railroad and the Milwaukee Road were both active in the southern end of the county. Along one stretch of the Jefferson River, which is followed by Montana Highway 2 (old U.S. Highway 10), you are actually traversing an ancient transportation route, created by the river, the railroads, and the federal highway. The Northern Pacific tracks are immediately next to the highway between the road and the Jefferson River; the Milwaukee corridor is on the opposite side of the river.

The most famous remnant of Montana’s mining era is the ghost town at Elkhorn. Of course the phrase ghost town is a brand name, not reality. People still live in Elkhorn–indeed more now than when I last visited 25 years ago. Another change is that the two primary landmarks of the town, Fraternity Hall and Gilliam Hall, have become a pocket state park, and are in better preservation shape than in the past.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

The adjacent Gillian Hall is also an important building, not as architecturally ornate as Fraternity Hall, but typical of mining town entertainment houses with bars and food on the first floor, and a dance hall on the second floor.

While the state park properties dominate what remains at Elkhorn, it is the general unplanned, ramshackle appearance and arrangement of the town that conveys a bit of what these bustling places were like over 130 years ago–residences and businesses alike thrown up quickly because everyone wanted to make their pile and then move on.

Elkhorn is not the only place of compelling vernacular architecture. Visible along Interstate I-15 is a remarkable set of log ranch buildings near Elk Park, once a major dairy center serving Butte during the 1st half of the twentieth century. John and Rudy Parini constructed the gambrel-roof log barn, to expand production available from an earlier log barn by their father, in c. 1929. The Parini ranch ever since has been a landmark for travelers between Butte and Helena.

Nearby is another frame dairy barn from the 1920s, constructed and operated by brothers George and William Francine. The barns are powerful artifacts of the interplay between urban development and agricultural innovation in Jefferson County in the 20th century.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte. The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

West of Whitehall is another 20th century roadside attraction, Lewis and Clark Caverns, a property with one of the most interesting conservation histories in the nation. It began as a privately developed site and then between 1908 and 1911 it became the Lewis and Clark Cavern National Monument during the administration of President William Howard Taft. Federal authorities believed that the caverns had a direct connection to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. The Corps of Discovery camped nearby on July 31, 1805, but had no direct association with the caverns. A portion of their route is within the park’s boundaries.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

Faith, and the persistence of early churches across rural Montana, is perhaps the most appropriate last theme to explore in Jefferson County. St. John the Evangelist (1880-1881) dominates the landscape of the Boulder Valley, along Montana Highway 69, like few other buildings. This straightforward statement of faith in a frame Gothic styled building, complete with a historic cemetery at the back, is a reminder of the early Catholic settlers of the valley, and how diversity is yet another reality of the Montana experience.

In the north end, Walkerville still shows this working side of domestic architecture well.

In the north end, Walkerville still shows this working side of domestic architecture well. Here are blocks upon blocks of the unpretentious, yet homey, dwellings of those drilling out a life below the ground. And elsewhere in the city you have surviving enclaves of the

Here are blocks upon blocks of the unpretentious, yet homey, dwellings of those drilling out a life below the ground. And elsewhere in the city you have surviving enclaves of the Some places speak to larger truths, often hidden in the landscape, of segregated spaces and segregated lives. This corner of Idaho Street (see below) was once home to the local African Methodist Episcopal church, which served a small surrounding neighborhood of black families.

Some places speak to larger truths, often hidden in the landscape, of segregated spaces and segregated lives. This corner of Idaho Street (see below) was once home to the local African Methodist Episcopal church, which served a small surrounding neighborhood of black families.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

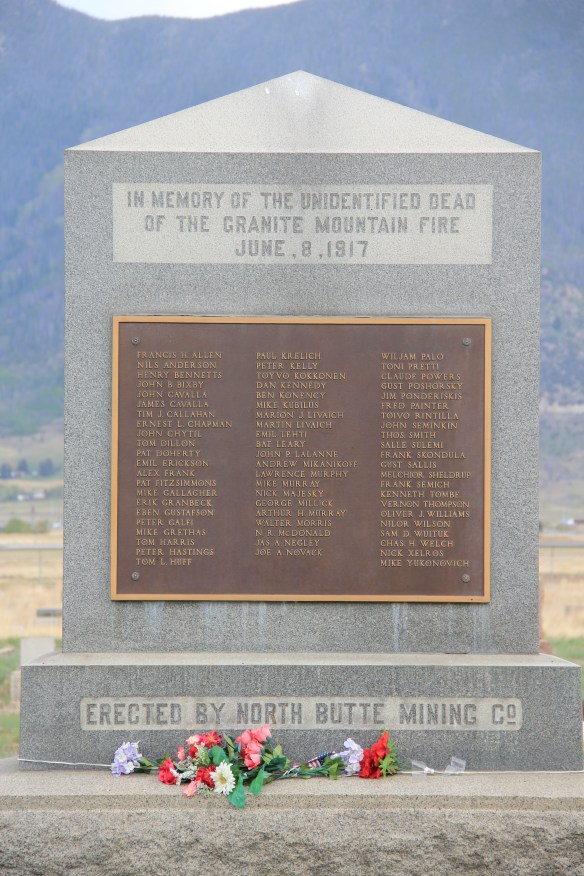

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot. The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation.

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation. There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible.

There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible. I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity.

Jefferson County, nestled as it is between the much larger population centers of Helena (Lewis and Clark County) and Butte (Silver Bow County), has often been neglected in any overview or study of Montana. But within the county’s historical landscape are places and stories that convey so much about Montana history and the historic properties that reflect its culture and identity. Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Let’s begin with the place so often in the news lately, the Montana Development Center, the location of the historic Montana Deaf and Dumb Asylum (1897-1898), a stately red brick Renaissance Revival-style building listed in the National Register of Historic Places in 1985. Since the building was being considered for listing, it was a top priority for the state historic preservation plan work in 1984. It remains in need of a new future 30-plus

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Another public institution once found in numbers across Montana but now found only in a few places is the high school dormitory, for students who spent the week in town rather than attempting to travel the distances between home and the high school on a daily basis. Boulder still has its high school dormitory from the 1920s, converted long ago into apartments.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Community halls represent another theme found in the Montana landscape; Jefferson County has an excellent example in its 1911 community hall in Clancy, which now serves as the local library. Likewise, fraternal lodges played a major role as community centers in early Montana history–the stone masonry of the two-story Boulder Basin Masonic Lodge makes an impressive Main Street statement.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Another good example of the early railroad development is at Corbin, where a major ore concentrator operated by the Helena Mining and Reduction Company was located in the 1880s. The concentrator handled 125 tons of ore every day. The concentrator is long gone but the foundations, while crumbling steadily, remain to convey its size and location. The tall steel train trestle overlooks the town, a powerful reminder of the connection between the rails and mines. It is part of the historic Montana Central line, first built as a wood trestle in 1888 and then replaced with the steel structure found today in 1902.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

Fraternity Hall was famous at the time of the state historic preservation plan survey as one of the best architectural examples of false front, Italianate style-influenced commercial buildings in the northern Rockies. The two photos below, one from 1985 and the other from 2013, show how its preservation has been enhanced under state guardianship. Its projecting bay and balcony are outstanding examples of the craftsmanship found in the vernacular architecture of the boom towns.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte.

The historic barn at the Jefferson Valley Museum is the Brooke Barn from 1914, another example of the dairy production then taking place in this part of Montana as the same time that the mines were booming in nearby Butte. The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair.

The adjacent rodeo grounds at Whitehall host in late July the Whitehall Bucking Horse Futurity competition and fair. The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it.

The bucking horse competition is not the only major summer event in the county. Along the old federal highway and the Jefferson River at Cardwell, music promoters took a historic highway truss bridge, converted it into a stage, and have been hosting the Headwaters Country Jam, the state’s biggest country music festival–a bit of Nashville every June in Montana: I have to love it. Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

Here is adaptive reuse at perhaps its ingenious best, and successful adaptive reuse projects are another constant theme found across Montana. Whitehall itself has a second example in the conversion of a 1920s Craftsman-style building on Legion Avenue (old U.S. Highway 10). Indeed, although travelers do not use the older federal highway much since the construction of the interstate, Whitehall has several good examples of roadside architecture–yes, another blog theme–along Legion Avenue, such as a Art Moderne-styled automobile dealership and a classic 1950s motel, complete with flashing neon sign.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

During the mid-1930s the Civilian Conservation Corps developed the park with new trails in the caverns; state and local authorities wanted more site development since the park stood along U.S. Highway 10, with potential tourism growth. In 1937-38, the federal government transferred the national monument to state control and in 1938 state officials launched Lewis and Clark Caverns as Montana’s first state park. Since my work 30 years ago, the state has re-energized the park with a new visitor center and interpretive exhibits that better convey the caverns’ significance, especially to Native Americans who had used the place centuries before Lewis and Clark passed nearby.

The public landscape of Anaconda has already been touched on in this blog–places like Washoe Park, the cemeteries, or Mitchell Stadium for instance. Now I want to go a bit deeper and look at public buildings, both government and education in this smelter city.

The public landscape of Anaconda has already been touched on in this blog–places like Washoe Park, the cemeteries, or Mitchell Stadium for instance. Now I want to go a bit deeper and look at public buildings, both government and education in this smelter city. Let’s begin with the only building in Anaconda that truly competes with the stack for visual dominance, the imposing classical revival-styled Deer Lodge County Courthouse. When copper baron Marcus Daly created Anaconda in the 1880s it may have been the industrial heart of Deer Lodge County but it was not the county seat. Daly was not concerned–his hopes centered on gaining the state capitol designation for his company town. When that did not happen, efforts returned to the county seat, which came to Anaconda in 1896. The courthouse was then built from 1898-1900.

Let’s begin with the only building in Anaconda that truly competes with the stack for visual dominance, the imposing classical revival-styled Deer Lodge County Courthouse. When copper baron Marcus Daly created Anaconda in the 1880s it may have been the industrial heart of Deer Lodge County but it was not the county seat. Daly was not concerned–his hopes centered on gaining the state capitol designation for his company town. When that did not happen, efforts returned to the county seat, which came to Anaconda in 1896. The courthouse was then built from 1898-1900.

in Montana is the lavish interior of the central lobby and then the upper story dome. The decorative upper dome frescoes come from a Milwaukee firm, Consolidated Artists. Newspaper accounts in 1900 recorded that the completed courthouse cost $100,000.

in Montana is the lavish interior of the central lobby and then the upper story dome. The decorative upper dome frescoes come from a Milwaukee firm, Consolidated Artists. Newspaper accounts in 1900 recorded that the completed courthouse cost $100,000. The bombastic classicism of the courthouse was at odds with the earlier more High Victorian style of City Hall, built 1895-1896, and attributed to J. H. Bartlett and Charles Lane. But classicism in the first third of the 20th century ruled in Anaconda’s public architecture, witness the Ionic colonnade of the 1931-1933 U.S. Post Office, from the office of Oscar Wenderoth.

The bombastic classicism of the courthouse was at odds with the earlier more High Victorian style of City Hall, built 1895-1896, and attributed to J. H. Bartlett and Charles Lane. But classicism in the first third of the 20th century ruled in Anaconda’s public architecture, witness the Ionic colonnade of the 1931-1933 U.S. Post Office, from the office of Oscar Wenderoth.

Once Anaconda, bursting at the seams following the boom of World War II, chose to upgrade its public schools, it took a decided turn away from traditional European influenced styles and embraced modernism, as defined in Montana during the 1950s.

Once Anaconda, bursting at the seams following the boom of World War II, chose to upgrade its public schools, it took a decided turn away from traditional European influenced styles and embraced modernism, as defined in Montana during the 1950s. The long, lean facade of Lincoln Elementary School (1950) began the trend. Its alternating bands of brick punctuated by bands of glass windows was a classic adaptation of International style in a regional setting. The modernist bent continued in 1950-1952 with the Anaconda Central High School, the private Catholic school, now known as the Fred Moody middle school, only a few blocks away. Except here the modernist style is softened by the use of local stone, giving it a rustic feel more in keeping with mid-20th century sensibilities and the Catholic diocese’s deliberate turn to modern style for its church buildings of the 1950s and 1960s (see my earlier post on College of Great Falls).

The long, lean facade of Lincoln Elementary School (1950) began the trend. Its alternating bands of brick punctuated by bands of glass windows was a classic adaptation of International style in a regional setting. The modernist bent continued in 1950-1952 with the Anaconda Central High School, the private Catholic school, now known as the Fred Moody middle school, only a few blocks away. Except here the modernist style is softened by the use of local stone, giving it a rustic feel more in keeping with mid-20th century sensibilities and the Catholic diocese’s deliberate turn to modern style for its church buildings of the 1950s and 1960s (see my earlier post on College of Great Falls).

In the preservation plan survey of 1984-1985 rarely did I give much attention to historic cemeteries–no one in the Helena office was focused on this property type and in all of my public meetings I never heard someone to make a case for cemeteries as either designed landscapes or community memory palaces. But in the thirty years since my work in the south has constantly drawn me to cemeteries, and when I began my re-survey of the Montana historic landscape in 2012 I was determined to look closely at cemeteries across the state.

In the preservation plan survey of 1984-1985 rarely did I give much attention to historic cemeteries–no one in the Helena office was focused on this property type and in all of my public meetings I never heard someone to make a case for cemeteries as either designed landscapes or community memory palaces. But in the thirty years since my work in the south has constantly drawn me to cemeteries, and when I began my re-survey of the Montana historic landscape in 2012 I was determined to look closely at cemeteries across the state. As i climbed the hill behind the courthouse and walked into Upper Hill Cemetery, I found acres of graves and monuments, a reflection of the town’s late 19th and early 20th century roots, and marker upon market that spoke to the ethnic groups, trade loyalties, and general working-class makeup of Anaconda. Here was a true artifact that I most certainly missed in 1984, and worthy of listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

As i climbed the hill behind the courthouse and walked into Upper Hill Cemetery, I found acres of graves and monuments, a reflection of the town’s late 19th and early 20th century roots, and marker upon market that spoke to the ethnic groups, trade loyalties, and general working-class makeup of Anaconda. Here was a true artifact that I most certainly missed in 1984, and worthy of listing in the National Register of Historic Places.

One unmistakable reality was that in death, as in life, Anaconda laborers could never leave the overwhelming presence of the Stack–wherever you go within the acres of the Upper Hill and Mt. Carmel Cemeteries you need leave the presence of the concrete and steel giant of the Anaconda Copper Company. Striking how many of the headstones face the stack.

One unmistakable reality was that in death, as in life, Anaconda laborers could never leave the overwhelming presence of the Stack–wherever you go within the acres of the Upper Hill and Mt. Carmel Cemeteries you need leave the presence of the concrete and steel giant of the Anaconda Copper Company. Striking how many of the headstones face the stack. Another reality was that fraternal loyalties–the brotherhood of labor–remained even as the bones that had once labored so diligently had decayed into dust. Fraternal organization often offered burial insurance–you were guaranteed a place within the fraternal plot even if your own birth family–who might be on the other side of the ocean–had long ago forgotten your face.

Another reality was that fraternal loyalties–the brotherhood of labor–remained even as the bones that had once labored so diligently had decayed into dust. Fraternal organization often offered burial insurance–you were guaranteed a place within the fraternal plot even if your own birth family–who might be on the other side of the ocean–had long ago forgotten your face. The Brotherhood of American Yeomen offered a gated plot, defined by a Victorian cast-iron fence that made a perfect rectangle.

The Brotherhood of American Yeomen offered a gated plot, defined by a Victorian cast-iron fence that made a perfect rectangle. The Knights of Pythias, on the other hand, offered a monumental cast-iron gate, emblazoned with their name, as the entrance to their fraternal plots.

The Knights of Pythias, on the other hand, offered a monumental cast-iron gate, emblazoned with their name, as the entrance to their fraternal plots.

Details and hidden meanings abound in this graveyard sculpture, and it is impossible to take it all in at once.

Details and hidden meanings abound in this graveyard sculpture, and it is impossible to take it all in at once.

Hayes Lavis, who died in the Great Depression, is one of the few of the Improved Order of Red Men identified in this fraternal grouping.

Hayes Lavis, who died in the Great Depression, is one of the few of the Improved Order of Red Men identified in this fraternal grouping. Military veterans are found throughout the cemetery–that is no surprise, but then it is surprising to see how many local men fought and died in the Spanish-American War of the late 1890s. The plot in their honor rests at one end of the cemetery, under the watchful gaze of the town “A” on the nearby hillside, but the low concrete wall that once defined the memorial is crumbling, just as our memory of this war and its veterans fade in the 21st century.

Military veterans are found throughout the cemetery–that is no surprise, but then it is surprising to see how many local men fought and died in the Spanish-American War of the late 1890s. The plot in their honor rests at one end of the cemetery, under the watchful gaze of the town “A” on the nearby hillside, but the low concrete wall that once defined the memorial is crumbling, just as our memory of this war and its veterans fade in the 21st century.

Family plots are also prevalent, with that of the Brown family and the loss of a child being particularly poignant.

Family plots are also prevalent, with that of the Brown family and the loss of a child being particularly poignant.

The craggy sandstone tower of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church is the town’s earliest religious architectural landmark, with the sanctuary dating to 1891. In 1978 t was among the first Anaconda landmarks to be listed in the National Register and remains one of the state’s most impressive examples of church architecture.

The craggy sandstone tower of St. Mark’s Episcopal Church is the town’s earliest religious architectural landmark, with the sanctuary dating to 1891. In 1978 t was among the first Anaconda landmarks to be listed in the National Register and remains one of the state’s most impressive examples of church architecture.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana. Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920.

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920. Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling.

Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling. Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda.

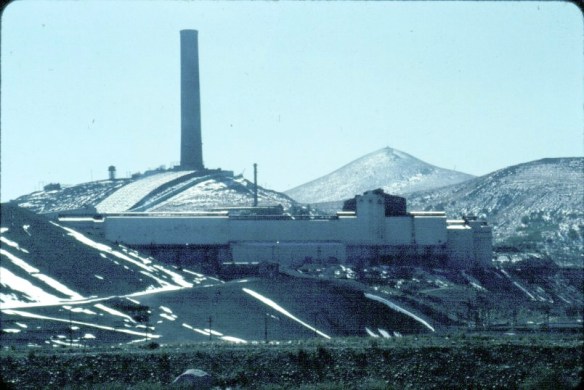

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda. In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

In my work across Montana in 1984-85 there was no more imposing structure than the smelter stack and works at Anaconda, in Deer Lodge County. The image above was one I used in the 20 plus listening sessions I had across the state in 1984, gathering perspectives and recommended properties for the state historic preservation plan. I used the stack because the smelter had just closed–and how this chapter in the state’s mining history could be preserved was on many minds.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth.

The Washoe Stack is one of the state’s most dominant man-made environments. For like the massive dams and reservoirs at Hungry Horse, Canyon Creek, and Fort Peck, there is the massiveness of the structure itself, and the thousands of surrounding acres impacted by the property. Unlike the lakes created by the dams of the first half of the 20th century, however, the stack left devastation in its wake, not recreation, not rebirth. The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of

The old gateway to the smelter introduces you to one lasting legacy of the stack–the tons of slag located along the highway leading in and out of Anaconda. The huge pile of seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

seems like some sort of black sand that has washed up on a beach rather the environmental spoils left by 100 years or production.

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

In the 1980s, the Atlantic Richfield Corporation, a later owner of the Washoe works, announced the stack’s closing and possible demolition. A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

That the place remained so intact in the early 1980s was impressive to me–that it remains that way 30 years later is a testament to local stewardship, and continued good times. The interior design of Art Deco details also remain to treat the eye and tempt

Few places in Montana, or for the nation for that matter, have benefited more from historic preservation and heritage development than Bozeman. To see a grain elevator complex find new uses and life in a century where grain elevators are typically a relic of a bygone era, tall hulking figures on the northern plains landscape, you discover that so much of our historic built environment can be re-imagined and put back into use.

Few places in Montana, or for the nation for that matter, have benefited more from historic preservation and heritage development than Bozeman. To see a grain elevator complex find new uses and life in a century where grain elevators are typically a relic of a bygone era, tall hulking figures on the northern plains landscape, you discover that so much of our historic built environment can be re-imagined and put back into use.

The town’s historic churches are other important anchors. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, St. James Episcopal Church is a distinguished statement of Gothic Revival executed in locally quarried sandstone designed by architect George Hancock of Fargo, North Dakota and built by local contractor James Campbell in 1890.

The town’s historic churches are other important anchors. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, St. James Episcopal Church is a distinguished statement of Gothic Revival executed in locally quarried sandstone designed by architect George Hancock of Fargo, North Dakota and built by local contractor James Campbell in 1890. Preservation efforts 30 years ago were focused on Main Street landmarks, with much success. But the combination of preservation and adaptive reuse has moved into the town’s railroad corridor with similar positive results, and the number of historic neighborhoods have multiplied.

Preservation efforts 30 years ago were focused on Main Street landmarks, with much success. But the combination of preservation and adaptive reuse has moved into the town’s railroad corridor with similar positive results, and the number of historic neighborhoods have multiplied.