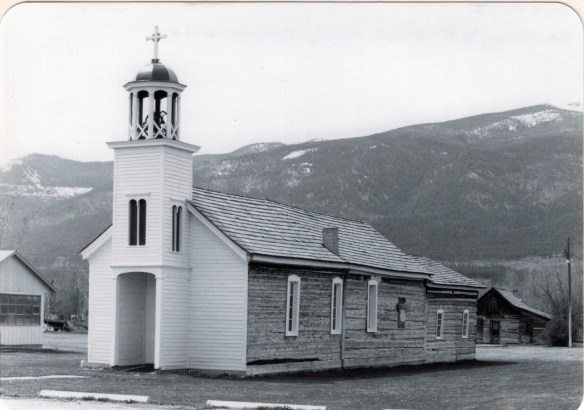

St. Mary’s Mission, photo 1984

When I arrived in Montana, fresh from Colonial Williamsburg, the state’s early history–the Native American story, the arrival of traders, first the French, then Lewis and Clark, and after that David Thompson out of Canada and the American Fur Company out of St. Louis–captured my attention. Later came Catholic missionaries, who struck particularly deep roots in the western valleys. All of those cultures, all of those conflicting needs, views, perceptions–it fascinated me, and those places of interaction and conflict became some of the focal points of my work. Thus, Stevensville was a place I eagerly explored.

I had my own copy of the lithograph above, a depiction of the Owen complex and “fort” from a federal survey expedition of the 1850s. So I first went to see Fort Owen State Monument.

Much to my surprise I found a “pocket” park, set almost like you will find historic sites within major cities, except here the site is next to a working ranch. Not what I expected.

Much to my surprise I found a “pocket” park, set almost like you will find historic sites within major cities, except here the site is next to a working ranch. Not what I expected.

But no complaints either. We are lucky that the ranchers shared a bit of the ranch and preserved some of the site’s history, especially the one remaining adobe barracks since this type of building and method of construction is so rare to find today. Most western forts are nothing more than archaeological sites.

But no complaints either. We are lucky that the ranchers shared a bit of the ranch and preserved some of the site’s history, especially the one remaining adobe barracks since this type of building and method of construction is so rare to find today. Most western forts are nothing more than archaeological sites.

The barracks has much to say but public interpretation here has not improved to the degree found at several other state parks in Montana like at First Nations in Cascade County. We get enough of the story to tantalize the average visitor and perhaps confound the scholar who wants more context.

The barracks has much to say but public interpretation here has not improved to the degree found at several other state parks in Montana like at First Nations in Cascade County. We get enough of the story to tantalize the average visitor and perhaps confound the scholar who wants more context.

The turn of the 20th century historic photo above shows how much was still here about 100 years ago but a storm ripped the roof off one of the barracks, and after all the construction Owen used here over 150 years ago was never meant to last for long. Traders wished to make an outpost impressive–why would anyone trade with a business that lacked substance?–but it made no business sense to build anything grandiose.

The turn of the 20th century historic photo above shows how much was still here about 100 years ago but a storm ripped the roof off one of the barracks, and after all the construction Owen used here over 150 years ago was never meant to last for long. Traders wished to make an outpost impressive–why would anyone trade with a business that lacked substance?–but it made no business sense to build anything grandiose.

To be clear–time had not turned still at Fort Owen since my last visit in 1984. You can see good conservation work everywhere and new exhibit cases improve the public presentation. But you still leave wanting more, and more land would be a start. You worry

that the open views to the greater landscape which remain as they were in the past might not last in the rapidly suburbanizing upper Bitterroot Valley. The Fort Owen park is still an invaluable national story set within a working ranch–but what if it becomes a pocket park surrounded by a 21st century suburb? The chance for meaningful archaeology–not to

that the open views to the greater landscape which remain as they were in the past might not last in the rapidly suburbanizing upper Bitterroot Valley. The Fort Owen park is still an invaluable national story set within a working ranch–but what if it becomes a pocket park surrounded by a 21st century suburb? The chance for meaningful archaeology–not to

rebuild the fort as what has happened at its cousins in Fort Benton and Fort Union–but to understand much more about the formative period of Montana history: that could be lost forever.

rebuild the fort as what has happened at its cousins in Fort Benton and Fort Union–but to understand much more about the formative period of Montana history: that could be lost forever.

Luckily at St. Mary’s Mission enough land has been secured that even as Stevensville expands (its population has jumped over 50% since 1984), perhaps the historic site’s future will not be that of a pocket park.

Luckily at St. Mary’s Mission enough land has been secured that even as Stevensville expands (its population has jumped over 50% since 1984), perhaps the historic site’s future will not be that of a pocket park.

Catholic missionaries led by Father DeSmet established the church here by 1841, although the present log chapel and attached school dates a generation later. This is still one of the state’s oldest buildings. The historic church is the setting for a largely memorial landscape honoring the priests, key Indian leaders such as Charlo, and those who set out

to create Christian outreach to the Native Americans, then and today. While the public interpretation here is robust, it is rarely a dialogue but more like a sermon, always on message, about the values the priests brought. What the Salish and other tribes thought about it all–from their perspective and in their words or traditions–is rarely given much attention. Yet the place itself, the setting, the use of logs, surviving furniture brought to the property in the 19th century: it all can say quite a bit if you stop and look and think.

St. Mary’s is powerful–in the same way that St. Peter’s Mission in Cascade County can be powerful–in how it juxtaposes the faith of the missionaries against the realities of the surrounding culture and landscape. Especially when you step into the historic cemetery

and look beyond the grave markers and memorial into the built environment and surrounding natural setting, St. Mary’s can imprint you in a profound way.

Let’s hope that future development in and around the historic mission keep these vistas as they are–for it is here that the modern story of the Bitterroot–meaning the last 175 years–begins.

Let’s hope that future development in and around the historic mission keep these vistas as they are–for it is here that the modern story of the Bitterroot–meaning the last 175 years–begins.

South 3rd Street also has a strong set of bungalows, Montana style, which means that they take all sorts of forms and use all sorts of building materials.

South 3rd Street also has a strong set of bungalows, Montana style, which means that they take all sorts of forms and use all sorts of building materials.

My favorite set of public buildings in Hamilton got back to the theme of town and ranch and how community institutions can link both. The Ravalli County Fairgrounds began on

My favorite set of public buildings in Hamilton got back to the theme of town and ranch and how community institutions can link both. The Ravalli County Fairgrounds began on 40 acres located south of downtown on the original road to Corvallis in 1913. Its remarkable set of buildings date from those early years into the present, and the Labor Day Rodeo is still one of the region’s best.

40 acres located south of downtown on the original road to Corvallis in 1913. Its remarkable set of buildings date from those early years into the present, and the Labor Day Rodeo is still one of the region’s best.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

contemporary styling of the Ravalli County Bank or the “new” county courthouse of 1976, a building that I totally dismissed in 1984 but now that it has reached the 40 year mark the design seems so much of its time, and a very interesting local reaction by the firm of Howland and Associates to the ne0-Colonial Revival that gripped so much of the nation during the American bicentennial.

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

Adaptive reuse had put some buildings back into use, such as the historic Creamery, once such an important link between town and ranch in the county. Other landmarks didn’t

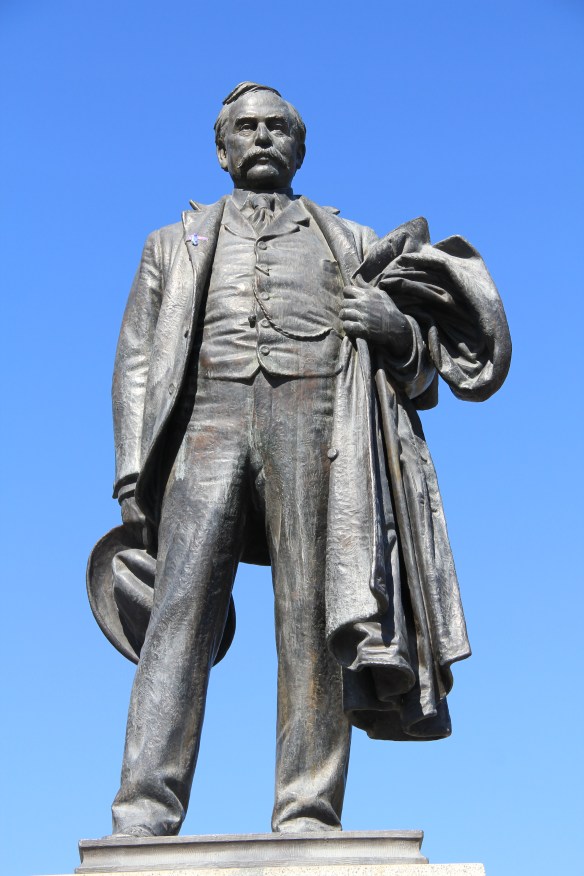

Marcus Daly, the copper magnate of Butte and Anaconda, certainly put his stamp on the landscape of Silver Bow and Deer Lodge counties. But not until the early 1980s did most Montanans understand that Daly too had shaped the landscape of the Bitterroot Valley with the creation and expansion of his Bitterroot Stock Farm, starting in 1886 and continuing even beyond his death in 1900.

Marcus Daly, the copper magnate of Butte and Anaconda, certainly put his stamp on the landscape of Silver Bow and Deer Lodge counties. But not until the early 1980s did most Montanans understand that Daly too had shaped the landscape of the Bitterroot Valley with the creation and expansion of his Bitterroot Stock Farm, starting in 1886 and continuing even beyond his death in 1900.

to have a place, on the other side of the divide from his dark, dank, smelly mining towns, where he and his family could escape and enjoy Montana’s open lands and skies. The ranch began with the purchase of the Chaffin family homestead in 1886. Daly immediately set forth to remodel and expand the older ranchhouse yet those changes only lasted three years when Daly replaced the first house with a rather grand and flamboyant Queen Anne-styled mansion and named it Riverside. Daly died in 1900 and Riverside’s last grand remodeling was guided by his wife, who looked to architect A. J. Gibson of Missoula to design a Colonial Revival-on-steroids mansion, which referenced the recent Roosevelt family mansion on the Hudson River in New York State.

to have a place, on the other side of the divide from his dark, dank, smelly mining towns, where he and his family could escape and enjoy Montana’s open lands and skies. The ranch began with the purchase of the Chaffin family homestead in 1886. Daly immediately set forth to remodel and expand the older ranchhouse yet those changes only lasted three years when Daly replaced the first house with a rather grand and flamboyant Queen Anne-styled mansion and named it Riverside. Daly died in 1900 and Riverside’s last grand remodeling was guided by his wife, who looked to architect A. J. Gibson of Missoula to design a Colonial Revival-on-steroids mansion, which referenced the recent Roosevelt family mansion on the Hudson River in New York State.

There is really nothing in the world of domestic architecture in Montana to compare to the Daly family’s Riverside estate. As we made our plans for the state historic preservation survey in 1984, I never imagined gaining access to this mysterious place. Then, suddenly, the owners decided to offer the property to someone–the state preferably but locals if necessary–who could transform it into a historic house museum and still working farm.

There is really nothing in the world of domestic architecture in Montana to compare to the Daly family’s Riverside estate. As we made our plans for the state historic preservation survey in 1984, I never imagined gaining access to this mysterious place. Then, suddenly, the owners decided to offer the property to someone–the state preferably but locals if necessary–who could transform it into a historic house museum and still working farm.

Indeed not far away is a 21st century sign of the super-rich and their imprint on the Montana landscape: the Stock Farm Club, a private, gated community for those who can afford it–and probably 99% cannot.

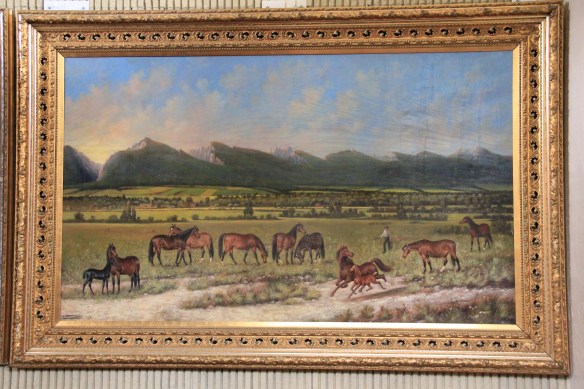

Indeed not far away is a 21st century sign of the super-rich and their imprint on the Montana landscape: the Stock Farm Club, a private, gated community for those who can afford it–and probably 99% cannot. As the historic promotional image above conveys, the Bitterroot Valley is an agricultural wonderland, but one dependent on irrigation and agricultural science. This image is on display at the Ravalli County Museum, which is located in the historic county courthouse from the turn of the 20th century.

As the historic promotional image above conveys, the Bitterroot Valley is an agricultural wonderland, but one dependent on irrigation and agricultural science. This image is on display at the Ravalli County Museum, which is located in the historic county courthouse from the turn of the 20th century. Local ranchers and boosters understood the economic potential of the valley if the land was properly nurtured. Some of the best evidence today is along the Eastside Highway,

Local ranchers and boosters understood the economic potential of the valley if the land was properly nurtured. Some of the best evidence today is along the Eastside Highway,

railroad spur through the valley. With its Four-Square style dwelling, the Bailey Ranch, immediately above, is a good example of the places of the 1910s-1920s. The Popham Ranch, seen below, is one of the oldest, dating to 1882.

railroad spur through the valley. With its Four-Square style dwelling, the Bailey Ranch, immediately above, is a good example of the places of the 1910s-1920s. The Popham Ranch, seen below, is one of the oldest, dating to 1882.

One major change in the Bitterroot over 30 years is the fruit industry has diminished and how many more small ranches and suburban-like developments crowd the once expansive agricultural wonderlands of the Bitterroot. The dwindling number that remain deserve careful attention for their future conservation before the working landscape disappears.

One major change in the Bitterroot over 30 years is the fruit industry has diminished and how many more small ranches and suburban-like developments crowd the once expansive agricultural wonderlands of the Bitterroot. The dwindling number that remain deserve careful attention for their future conservation before the working landscape disappears.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong. Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area. Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.