There are few places in the nation more important than the broad river valley at the confluence of the Judith and Missouri rivers in central Montana, a place only accessible by historic gravel roads. When I first visited in 1984, I came from the Fergus County side through Winifred.

Why is Judith Landing so important? It was a vital and frequently used crossroads for Northern Plains tribes for centuries. Then in 1805 as Lewis and Clark traveled on the Missouri, they camped at the confluence (private property today). In 1844, The American Fur Company established Fort Chardon, a short-lived trading post.

In 1846 Indigenous leaders of several tribes met at Council Island to discuss relations between the Blackfeet and other northwest tribes. In 1855 leaders from the Blackfeet, Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Nez Perce returned to Council Island to negotiate the Lame Bull treaty, which established communal hunting areas and paved the way for white settlement in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

Settlement first came with trading posts, serving a nearby army base, Camp Cooke (1866-1870) and connecting steamboat traffic on the Missouri to nearly mining camps (like Maiden). When the U.S. government moved the base, Fort Benton merchant T.C. Power developed his own businesses and post at Judith Landing and established “Fort Clagett” to the immediate west. In the 1880s he partnered with Gilman Norris to create the famous PN Ranch from the remnants of these early settlement efforts.

Visiting this place was a major goal of the 1984 historic preservation plan survey. At that time the ranch was still operating as a ranch and the one slide that I took shows several of the historic and new ranch buildings, yes from a distance because in the work I always respected private property boundaries.

Over the next 40 years I worked in Montana many times but never made a return to Judith Landing. I knew that the historic buildings of the PN ranch were there and that a National Register district existed affording some protection. Then in late 2024 came the news that Montana State Parks was acquiring 109 acres of the historic property and would create the Judith Landing State Park. I couldn’t wait to return and visited in late September 2025.

At that time there had been little in the way of “park development.” I hope it largely stays that way because the sense of time and place conveyed by the rustic, rugged surroundings is overwhelming. You can be lost in history.

The half-dovetail “mail barn” was moved to its location on the ranch about 1890. It continued to serve as a post office until 1919.

The stone warehouse was severely damaged in a flood 50 years ago—but it is hanging on, and indicates how important trade and commodities were here 150 years ago. It operated as a store until 1934 and then became a barn for the next 40 years until the flood of 1975.

Gilman and Pauline Norris’s own ranch house, a turn of the twentieth century Shingle-style beauty, speaks to the ranch’s success. perhaps it can be restored as a future park interpretive center, open in the summer.

The important point is that, now, finally, Judith Landing is a state park, conserving one of the most remarkable places of the northern plains.

On the outskirts of town, the 1920s monument to David Thompson was the centerpiece of the town’s heritage tourism attractions in 1984-1985, now it is more of an afterthought. David Thompson was a Welsh-Canadian who established the first trading post in this river valley, called Saleesh House, for the tribe with whom this veteran of both the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company had targeted for the fur trade. His last visit to Saleesh House came in the winter of 1812. Thompson, I thought in 1984, was a very important figure in Montana history but increasingly a neglected trader–in fact most of the early traders, like those of the American Fur Company on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, are neglected, even though significant places associated with them remain intact on the state’s landscape.

On the outskirts of town, the 1920s monument to David Thompson was the centerpiece of the town’s heritage tourism attractions in 1984-1985, now it is more of an afterthought. David Thompson was a Welsh-Canadian who established the first trading post in this river valley, called Saleesh House, for the tribe with whom this veteran of both the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company had targeted for the fur trade. His last visit to Saleesh House came in the winter of 1812. Thompson, I thought in 1984, was a very important figure in Montana history but increasingly a neglected trader–in fact most of the early traders, like those of the American Fur Company on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, are neglected, even though significant places associated with them remain intact on the state’s landscape. About one hundred years after David Thompson’s last winter at Saleesh House, an entirely different landscape emerged along the Clark’s Fork River, one that introduced the recent technology of electricity to the region. To support and encourage the development of hydroelectric facilities, the city of Thompson Falls combined with investors to build what became known as the “High Bridge,” a way for automobile traffic to cross this gorge in the Clark’s Fork and unite settlement on both sides of the river.

About one hundred years after David Thompson’s last winter at Saleesh House, an entirely different landscape emerged along the Clark’s Fork River, one that introduced the recent technology of electricity to the region. To support and encourage the development of hydroelectric facilities, the city of Thompson Falls combined with investors to build what became known as the “High Bridge,” a way for automobile traffic to cross this gorge in the Clark’s Fork and unite settlement on both sides of the river. The High Bridge was an early 20th century Montana engineering marvel. It was 588 feet in length, designed for automobile traffic, with a 18-feet wide deck standing on a combination of Pratt and Parker trusses. It is the longest bridge of its kind in Montana.

The High Bridge was an early 20th century Montana engineering marvel. It was 588 feet in length, designed for automobile traffic, with a 18-feet wide deck standing on a combination of Pratt and Parker trusses. It is the longest bridge of its kind in Montana.

But within two years, residents and officials combined together to place the bridges and hydroelectric facilities in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. They were preserved, but still not used, for a generation.

But within two years, residents and officials combined together to place the bridges and hydroelectric facilities in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. They were preserved, but still not used, for a generation. In 2009-2010, residents worked with local, state, and federal government officials to restore the bridge, add a pedestrian deck, and to open the bridge and either side of the bridge as a public park. Funding in part came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, one of the ways that short-lived federal building effort benefited historic preservation in Montana small towns.

In 2009-2010, residents worked with local, state, and federal government officials to restore the bridge, add a pedestrian deck, and to open the bridge and either side of the bridge as a public park. Funding in part came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, one of the ways that short-lived federal building effort benefited historic preservation in Montana small towns. The High Bridge experience not only reconnected Thompson Falls to its river roots, it also creates an unique experience for heritage travelers. The site is not that far different from 100 years ago, giving you the chance to cross a river and peer below but also to realize just how “wild” automobile traffic was in the 1910s and 1920s.

The High Bridge experience not only reconnected Thompson Falls to its river roots, it also creates an unique experience for heritage travelers. The site is not that far different from 100 years ago, giving you the chance to cross a river and peer below but also to realize just how “wild” automobile traffic was in the 1910s and 1920s. Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls.

Sanders County, like many of the places that are on the western side of the Rocky Mountains, has boomed in the last 25 years, from a population over 8,000 to the current estimated population of 11,300. It is close to Missoula, the eastern side is not far from Flathead Lake, Montana Highway 200 runs from Dixon to the end of the county at Heron. With wide valleys and narrow gorges created by both the Flathead and Clark’s Fork Rivers, which meet outside the town of Paradise, Sanders County is frankly a spectacular landscape, with dramatic mountain views framing open plains, such as the image above and the awesome gorge of Clark’s Fork River, below at Thompson Falls. The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28.

The eastern side of the county is just as dramatic just in a far different way. For centuries First Peoples hunted game and dug the camas root in the broad upland prairie that became known as Camas Prairie, crossed now by Montana Highway 28. Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly,

Then, leading from the county’s southeastern edge there is the beautiful Flathead River Valley, followed by Montana Highway 200, from Dixon to Paradise, and most importantly, a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast.

a transportation route initially carved as a trail by the First Peoples who became the nucleus of today’s Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribe and much later engineered into a major corridor by the tracks of the Northern Pacific Railroad, as it stretched westward from Missoula to the west coast. In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century.

In its wake, the Northern Pacific created most of the county’s townsites by locating sidings along the track. Substantial settlement arrived once the federal government opened lands for the homesteading boom in the early 20th century. Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Dixon, named for the former Montana governor Joseph Dixon, is one of the remaining railroad/homesteading towns along the Flathead River. The fate of the community bar, above, is symbolic of the recent history of the town, one of population decline.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

Local residents are being excellent stewards of this captivating property–certainly one of my favorite spots in the state combining landscape with architecture with history. The architect was the Missoula designer H. E. Kirkemo, and the school was completed in 1940, near the end of the New Deal school building programs.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

The school had just closed its doors for good when I lasted visited but the restoration planning has been underway ever since. I look forward to my next visit to Paradise to experience the final results. Near the school is another historic community property, the Paradise Cemetery, where tombstones mark the names of those who worked so long for the railroad and for the creation of this place within the Clark’s Fork River Valley.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

Much to my surprise I found a “pocket” park, set almost like you will find historic sites within major cities, except here the site is next to a working ranch. Not what I expected.

Much to my surprise I found a “pocket” park, set almost like you will find historic sites within major cities, except here the site is next to a working ranch. Not what I expected. But no complaints either. We are lucky that the ranchers shared a bit of the ranch and preserved some of the site’s history, especially the one remaining adobe barracks since this type of building and method of construction is so rare to find today. Most western forts are nothing more than archaeological sites.

But no complaints either. We are lucky that the ranchers shared a bit of the ranch and preserved some of the site’s history, especially the one remaining adobe barracks since this type of building and method of construction is so rare to find today. Most western forts are nothing more than archaeological sites. The barracks has much to say but public interpretation here has not improved to the degree found at several other state parks in Montana like at First Nations in Cascade County. We get enough of the story to tantalize the average visitor and perhaps confound the scholar who wants more context.

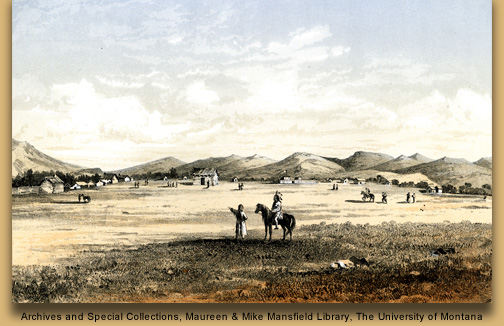

The barracks has much to say but public interpretation here has not improved to the degree found at several other state parks in Montana like at First Nations in Cascade County. We get enough of the story to tantalize the average visitor and perhaps confound the scholar who wants more context. The turn of the 20th century historic photo above shows how much was still here about 100 years ago but a storm ripped the roof off one of the barracks, and after all the construction Owen used here over 150 years ago was never meant to last for long. Traders wished to make an outpost impressive–why would anyone trade with a business that lacked substance?–but it made no business sense to build anything grandiose.

The turn of the 20th century historic photo above shows how much was still here about 100 years ago but a storm ripped the roof off one of the barracks, and after all the construction Owen used here over 150 years ago was never meant to last for long. Traders wished to make an outpost impressive–why would anyone trade with a business that lacked substance?–but it made no business sense to build anything grandiose.

that the open views to the greater landscape which remain as they were in the past might not last in the rapidly suburbanizing upper Bitterroot Valley. The Fort Owen park is still an invaluable national story set within a working ranch–but what if it becomes a pocket park surrounded by a 21st century suburb? The chance for meaningful archaeology–not to

that the open views to the greater landscape which remain as they were in the past might not last in the rapidly suburbanizing upper Bitterroot Valley. The Fort Owen park is still an invaluable national story set within a working ranch–but what if it becomes a pocket park surrounded by a 21st century suburb? The chance for meaningful archaeology–not to rebuild the fort as what has happened at its cousins in Fort Benton and Fort Union–but to understand much more about the formative period of Montana history: that could be lost forever.

rebuild the fort as what has happened at its cousins in Fort Benton and Fort Union–but to understand much more about the formative period of Montana history: that could be lost forever. Luckily at St. Mary’s Mission enough land has been secured that even as Stevensville expands (its population has jumped over 50% since 1984), perhaps the historic site’s future will not be that of a pocket park.

Luckily at St. Mary’s Mission enough land has been secured that even as Stevensville expands (its population has jumped over 50% since 1984), perhaps the historic site’s future will not be that of a pocket park.

Let’s hope that future development in and around the historic mission keep these vistas as they are–for it is here that the modern story of the Bitterroot–meaning the last 175 years–begins.

Let’s hope that future development in and around the historic mission keep these vistas as they are–for it is here that the modern story of the Bitterroot–meaning the last 175 years–begins.