Boulder (population 1200 in 2020) is the seat of Jefferson County. Since the time of my historic preservation survey of Montana in 1984-1985, Boulder has lost about 200 residents (the state’s closure of the historic Montana Development Center a few years ago definitely didn’t help). But there remains a vibrancy and hope to the place, centered as it is within easy distance of a larger rural boom in Lewis and Clark, Silver Bow, and Gallatin counties.

The cemetery is on a hill overlooking the town with the entrance modern by a modern sign formed out of stones from the Boulder River. The view from the top of the cemetery provides a great overview of the town’s residential, commercial, and government areas.

As observed in many other Montana cemeteries that date to the nineteenth century, the Boulder Cemetery has several family plots marked by Victorian posts and fence, even though over time some of the fencing may have been replaced by other wire panels.

The cemeteries have many Victorian-themed grave markers as the previous images have shown. The urn-topped marker for Michael Lynch, a native of Ireland who died in 1910, is an excellent example of Victorian grave art in the cemetery.

There are several historic markers for veterans of the Indian Wars of the 19th century, and a beautiful stone marker for John Norman, who died in a World War I training camp in 1918.

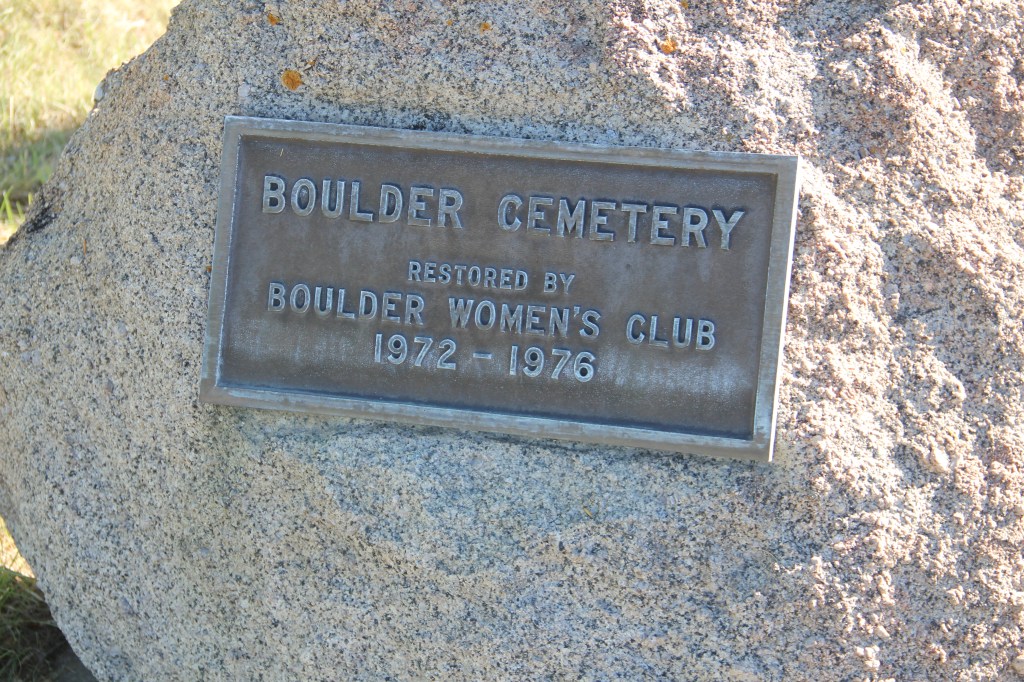

The Boulder Cemetery could be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places as a marker of early settlement and development of the town and for its cemetery art. But then a simple boulder marker tells of a more contemporary significance. The Boulder Women’s Club restored the cemetery from 1972-1976 as its contribution to the American Bicentennial commemoration. The Bicentennial saw thousands of history projects and events take place all over the nation. Here is a place that local women carried out a preservation project that clearly created a new place for community pride and identify, marking a unique and lasting contribution to the Bicentennial period. Impressive.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

The county library, above, is small but busy, a reminder of how important these public buildings can be. About 5 years ago, the time of my last visit, Scobey still had its own medical center, below, as well as a distinctive post office, different from many in the region due to its modernist style.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

My first trip to Beaverhead County in 1981 had two primary goals–and the first was to explore Bannack, the roots of Montana Territory, and one of its best connections to Civil War America. As this simple wooden sign below remarks, here in 1862 the first gold strike in what became Montana Territory occurred.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains.

a path because the glistening bits of metal loose in the sands of the creek had never interested the Native Americans but news of the find was enough to drive easterners, many of them southerners, away from the landscape of war and into a wholly different place, crested by beautiful mountains. Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years.

Grasshopper Creek was not much of place then, and even now, but this stream of water became the source of a boom that eventually reshaped the boundaries of the northern Rockies and nearby its banks grew the town of Bannack, a name taken in part from the Bannock Indians who had used this landscape in far different ways for many years. The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution

The story of the preservation of Bannock begins with local land owners, who protected the site, and kept most of the buildings from being scattered across the region. There was little official interest in the place at first. The state Daughters of American Revolution marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

marked it in 1925, otherwise the buildings remained, some in use as residences or for public purposes, others melting away in the demanding climate. The Boveys moved the Goodrich Hotel to their preservation project at Virginia City and transformed it into the Fairweather Inn, which is still in use as lodging.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

In 1954, the Beaverhead County Historical Society transferred about 1/3 of the present property to the state for protection and development as a state park. Not until 1961 did the National Park Service recognize the town as a National Historic Landmark.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies.

Gritty, dusty, forlorn: yes, Bannack is the real deal for anyone wanting to explore ground zero of the gold rush era in Montana, and to think about how in the midst of the great Civil War, federal officials found time to support adventurous citizens to launch a new territory in forgotten expanses of the northern Rockies. I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer

I thought that 30 years ago I “got” Bannack–there wasn’t much that I missed here. I was wrong. Probably like thousands of other visitors who fly into the town, and leave just as quickly, I missed what is still called the “new” town cemetery. Almost hidden in the sagebrush along Bannack Road, the “new” cemetery is not Boot Hill–where is Plummer buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.

buried people still want to know–but it is a remarkable place of hand-carved tombstones, others rich with Victorian imagery, and a few that are poignant reminders of the Civil War veterans who came here and stayed.