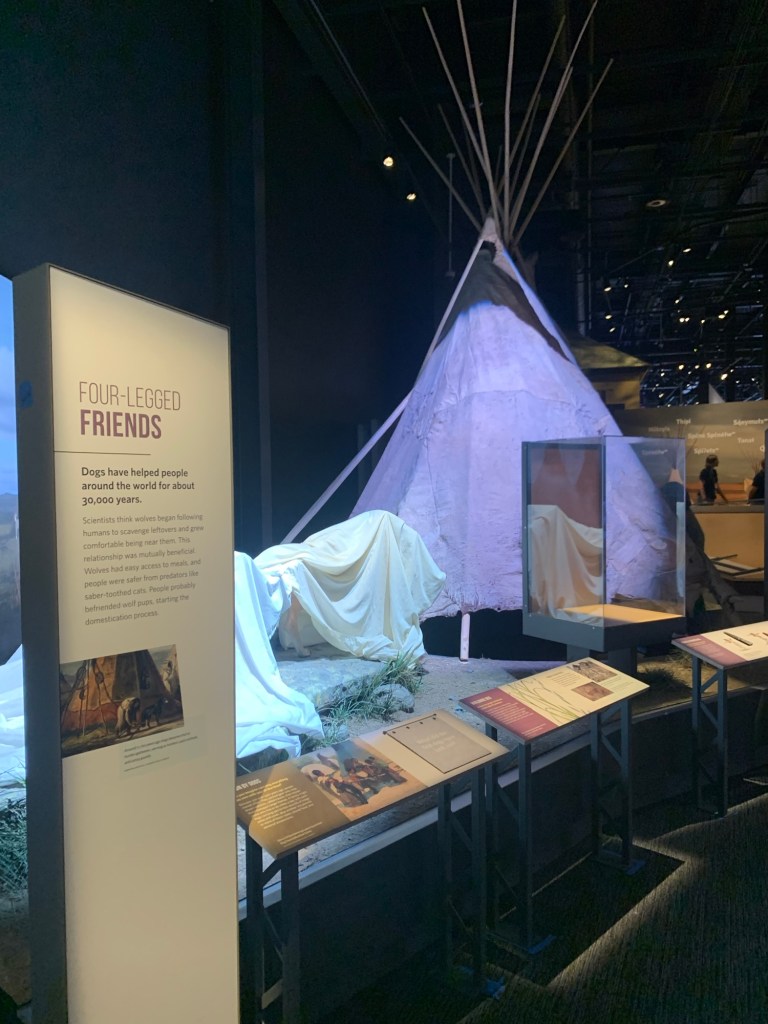

Like hundreds of others who crowded into the new wing of the Montana Historical Society to get a sneak peek of the new state history exhibit, titled Montana Homeland, I expected to be dazzled. After all it had been 40 years since MHS had last updated its primary history exhibit.

The architects gave the exhibit designers a huge lofty space and there are tipis galore, their height dominating everything around them, challenged only by a reproduction headframe.

The headframe is in a corner and fades into the background unlike the tips which literally command most views within the exhibit, even at the end.

The message of the exhibit team is not subtle—Indigenous people dominate the past of the lands that today comprise Montana—but the hand of people in the last 100 years also dominate the built environment. The exhibit is missing the one lofty structure that is still found everywhere, representing a property type that also ties together so much of the state’s history—the Grain Elevator. Wish there was one in these lofty spaces. It helps to explain the impact of agriculture, the homesteading era, railroad lines, and town creation.

20th century Montana is thus far greatly underrepresented in the exhibit, almost as if the attitude was that nothing matters that much after the homesteaders—let’s wrap this baby up!

But by so doing you downplay the huge impact of the engineered landscape on the homeland, especially the federal irrigation programs that produced mammoth structures that reoriented entire places—Gibson Dam comes right to mind, and then there’s Fort Peck.

Irrigation also is central because of the diversity of peoples who came in the wake of the canals and ditches. Not just the Indigenous, not just the miners but the farmers and ranchers added to the Montana mosaic. A working headgate—would that help propel the story?

Right now the answer is no. There are many, many words in this exhibit, and, as people seem to want to do nowadays, the words are often preachy. I wondered about the so 2020s final section, where visitors are implored to live better together by accepting diverse peoples.

Montana is nothing but a melding of diverse peoples, from 14 tribes, the 17-18 ethic groups at Butte, the Danes of the northeast, the Finns of the Clark’s fork, and the Mennonites of the central plains, etc etc. if they had started challenging character of the actual Montana landscape had been front and center, then let history unfold to show how many people of all sorts of origins and motives tried to carve a life from it—you would have a different exhibit and one not so preachy.

Let’s hope the Final Cut has many less words, many more objects and a greater embrace of the state’s 20th century transformations.

Fort Kipp Cemetery, above, is one of those place, nestled on the river bluffs overlooking the Missouri River. On a larger scale but still intimate, personal, and compelling is the city cemetery of Red Lodge, hundreds of miles away. Here surrounded by the mountains

Fort Kipp Cemetery, above, is one of those place, nestled on the river bluffs overlooking the Missouri River. On a larger scale but still intimate, personal, and compelling is the city cemetery of Red Lodge, hundreds of miles away. Here surrounded by the mountains

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire. The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects.

The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects. The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena.

The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena. Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.

Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.  The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings.

The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings. While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959.

While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959. It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day.

It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day. Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.

modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks.

As you leave the Missouri Headwaters State Park access road (Montana 286) and return south to old U.S. Highway 10, you encounter a plaintive sign hoping to attract the thousands of heritage tourists who come to the state park–go a bit farther south and west and find the town of Three Forks. The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

The story of Three Forks, on the western edge of Gallatin County, is not of rivers but of railroads, of how both the Northern Pacific and the Milwaukee Road corridors shaped this part of the state at the end of the first decade of the 20th century.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town. How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history.

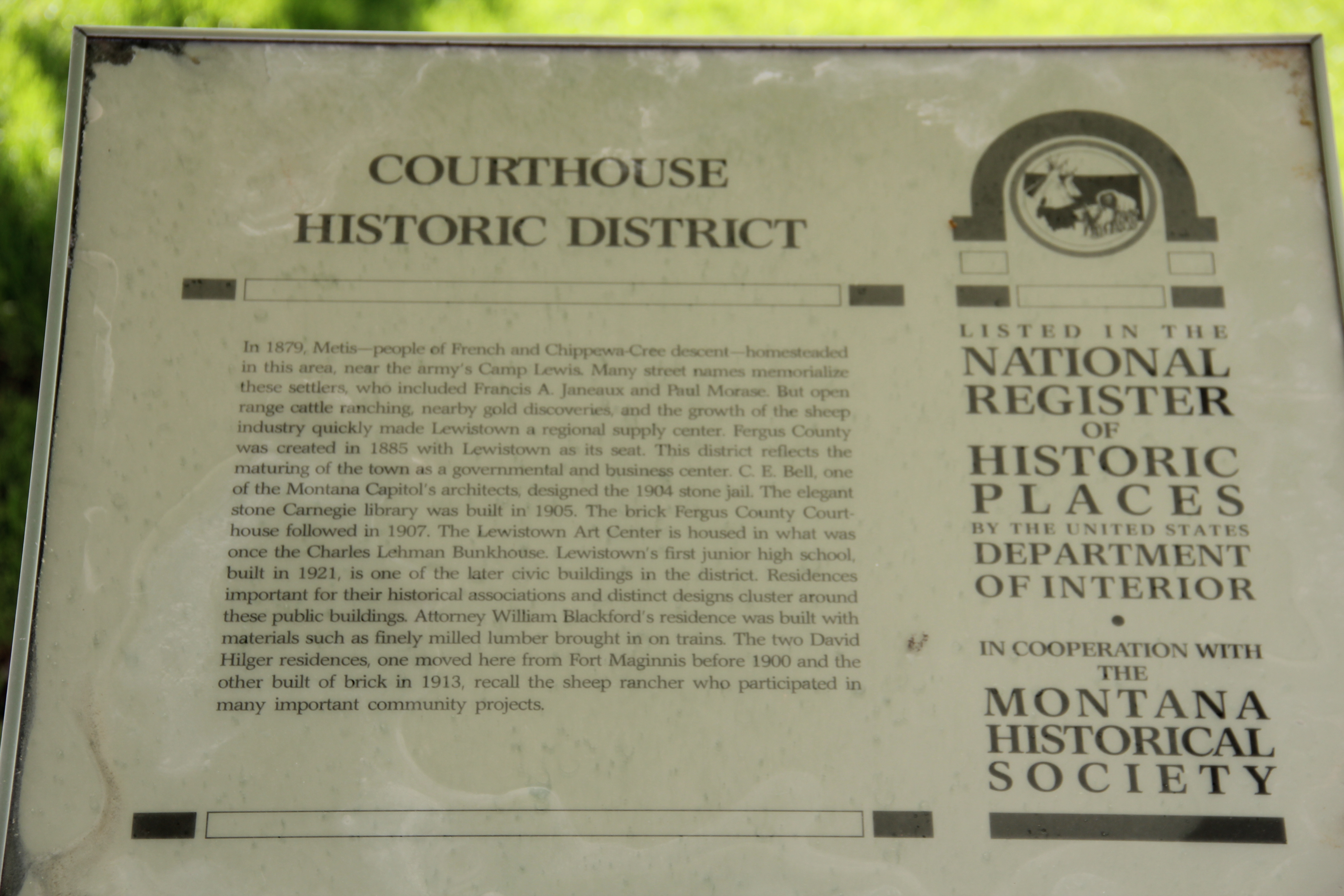

How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history. Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society.

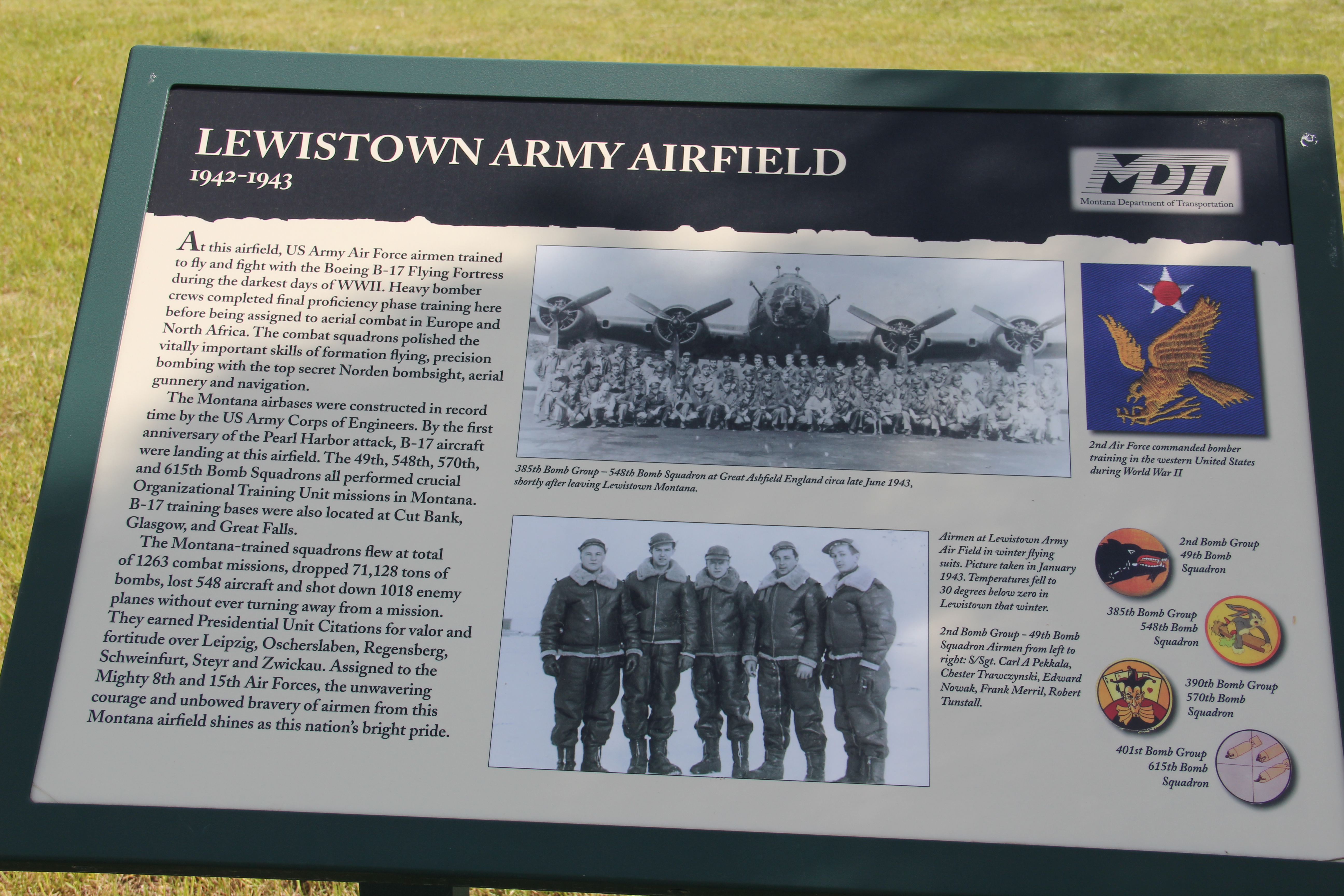

Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society. What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense.

What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense. Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation.

Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation. Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods. The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and

The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today.

residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today. As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis.

As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis. Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.