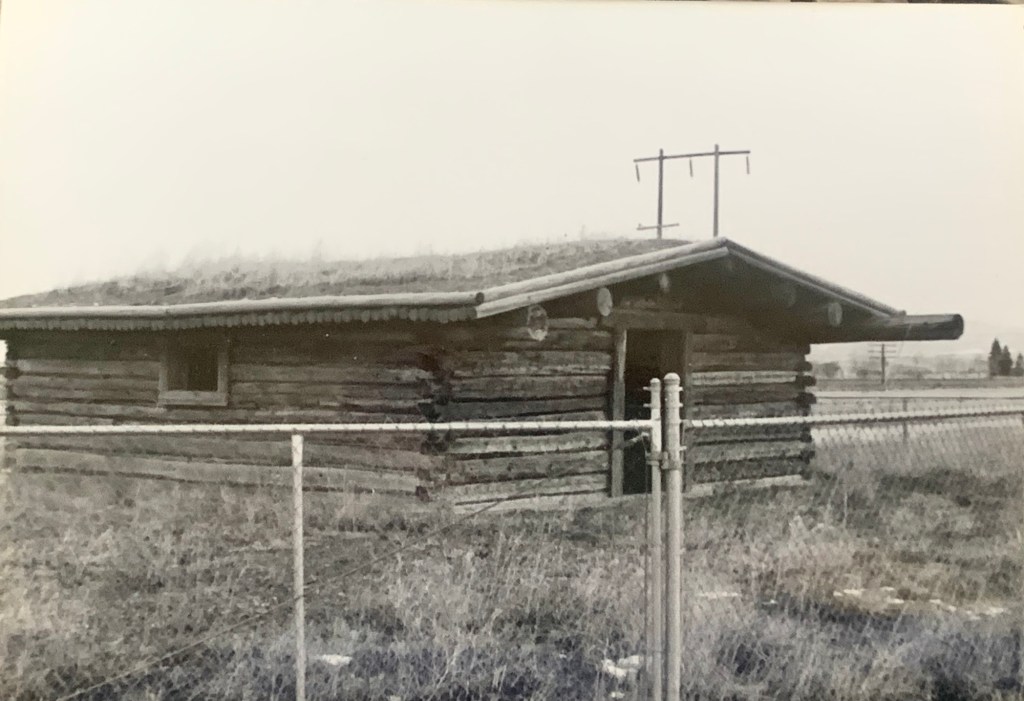

As the Missouri River winds its way into the mountains of Montana, one of my favorite stops for 40 years is the town of Craig. Ben Stickney was the first to farm here in the 1870s. He and Frank Wagner also established a ferry crossing. Other early settlers were Warren and Eliza Craig who platted a townsite named Craig once the construction of the Montana Central Railroad between Great Falls and Helena was finished in late 1887. By 1890, the town had 77 residents.

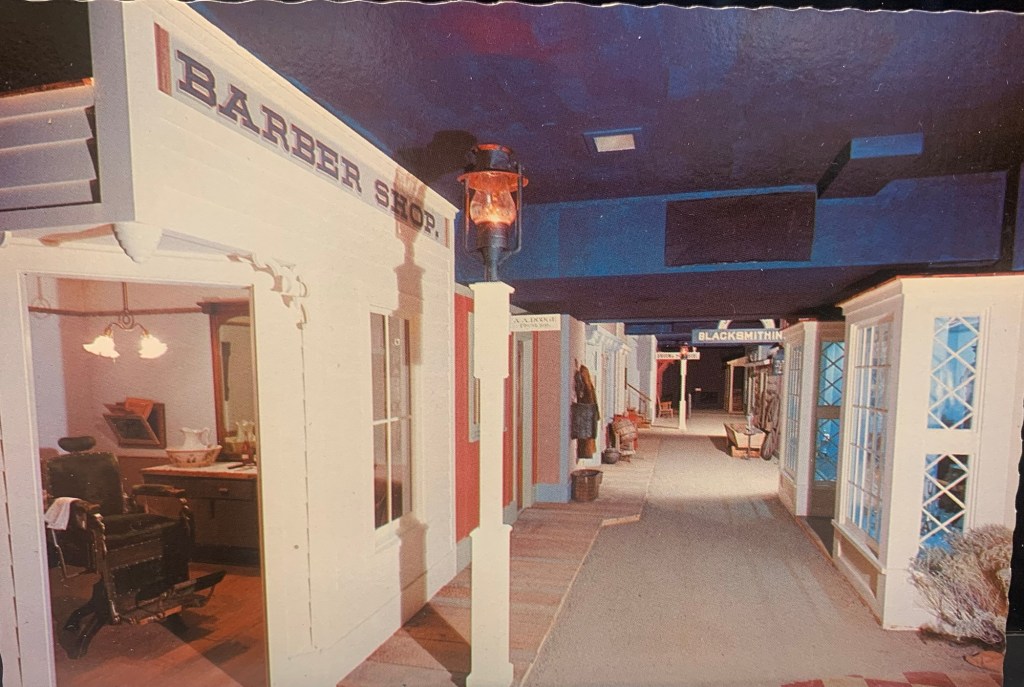

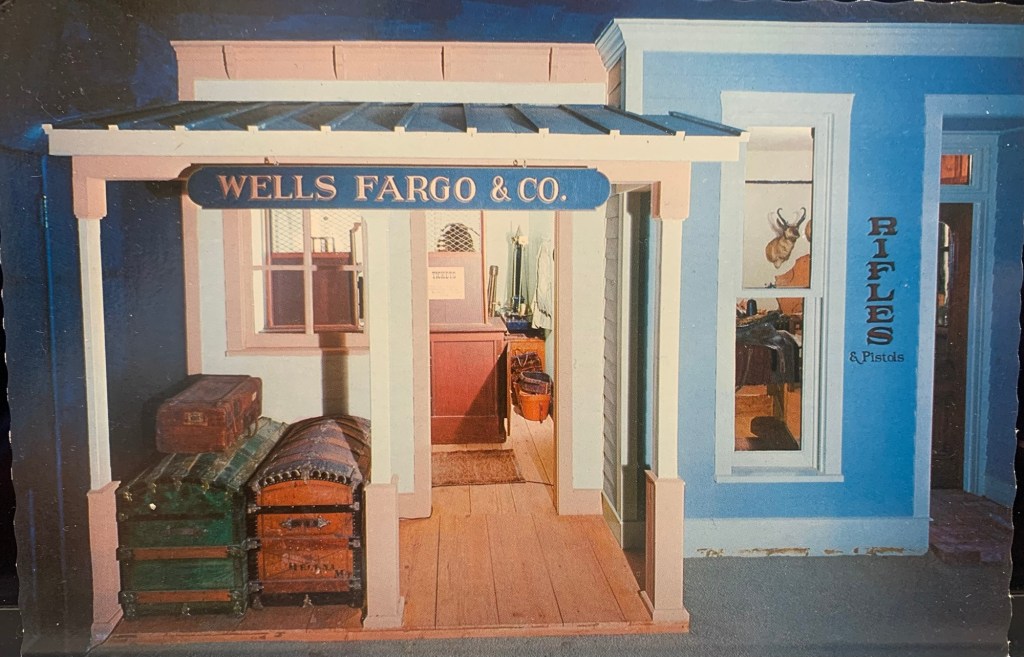

The story of Craig in its early years was all about the railroad corridor, with houses and businesses arranged on either side of the tracks.

The Missouri River defined the east side of town as it closely paralleled the tracks. Then in 1902-1904 came the construction of a steel bridge, which replaced the ferry.

The bridge made Craig a crossroad town but it never grew that much in the next decades.

When in the 1930s the state constructed its section of U.S. Highway 91, the improved transportation led to the growth of the local school, which closed in the 21st century and now serves as a community building.

Residents also established a volunteer fire hall next to the school.

At the time historian Jon Axline documented the steel bridge c. 2002, he noted that Craig had only a bar and a fishing shop. There was not much else left. The Craig Bar is still there if you want a throwback small town bar experience.

An almost totally different Craig has emerged since the construction of the concrete bridge 20 years ago. New businesses that cater to the ever-growing fly fishing industry are everywhere it seems. Floaters and fisherman crowd the landing on weekends and in the summer.

Big Sky Journal has nicknamed Craig as Fish Town, a “quintessential fishing village” on the Missouri River. Fishing and recreation now have replaced its earlier reputation as a transportation crossroads in the Missouri River Canyon. And the concrete bridge is like a slash across the river compared to the beautiful steel trusses of the first bridge.