Virginia City in the 19th century was a living, breathing place, and continues so today. After all it is not all a recreated outdoor museum, it is the location, still, of the Madison County Courthouse and is the seat of Madison County. The courthouse is one of the great 19th century public buildings of Montana.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today.

Nevada City, just a stone’s throw away, was and is different. Here stood the historic Gothic Revival-styled Finney House, built c. 1863-64, along with about a dozen or so other historic buildings.

There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

Today I think about Nevada City differently. As a historic district of related buildings, placed here in a coherent plan c. 1959-1960 that was designed to convey to the public a range of the western experience during the northern Rockies gold rush era, and to serve smack dab on the side of Montana Highway 287 as a heritage tourism resource, Nevada City is due a re-assessment. These once scattered buildings have established a new context over the last 30 years. And, like in Virginia City, the Montana Heritage Foundation is doing what it can to repair and conserve this unique built environment.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Behind the fenced barriers of the outdoor museum (unlike several building zoos in the state this place is just not open without barriers for tourists to visit), you can encounter significant properties associated with the vigilante movement, such as this spot associated with the hanging of George Ives in 1863.

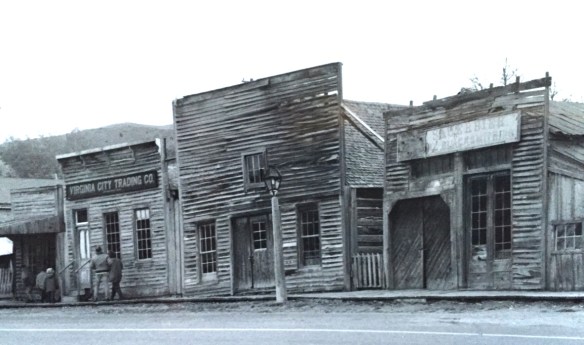

Another theme is vernacular architecture on the gold rush frontier, and how even the mundane false front style of so many buildings at that time could be more elaborate, and expressive. The craftsmanship of the original buildings would need to be carefully assessed to determine whether what you see today reflects 150 years ago or the craftsmanship of restoration 50 years ago.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

Therefore, when in 1984-1985 I made the decision to give Nevada City little more than a nod, that was ok–the restored village effort was then only 20-25 years old. Not very historic, although the buildings came from history. Thirty years later, my thoughts have changed dramatically. Nevada City is much more than a passing interest. In fact, it is a

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

Virginia City was Montana’s first effort to protect a large district of buildings, and it took place through private initiative. In the late 1980s, out of the earlier fieldwork that decade, I was preparing an article on Montana’s preserved landscapes, and eventually the piece appeared in a book on historic preservation in the West published by the University of New Mexico Press. Virginia City had always intrigued me, because of how the Bovey family admitted to anyone who would listen that their encouragement came from the success of Colonial Williamsburg, in Virginia, where I had began my career.

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

“The Bovey family lost interest in the project during the 1990s and at one time it appeared that many of the valuable collections would be sold and dispersed. The State of Montana and thousands of interested citizens stepped forward and raised the money to acquire the

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

I am speaking instead of the very interesting historic city cemetery, just a bit to the north. It has a wide of grave markers, that show the confluence of folk burial practices of the mid to late 19th century with the more popular, and mass produced imagery of Victorian burial markers. There are, just as in southern cemeteries, family plots marked by Victorian cast-iron fences. Or those, in a commonly found variation, that have a low stone wall marking the family plots.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

Callaway’s grave is one of several of individuals significant in the territorial era. Thomas J. Dimsdale, the chronicler of the vigilante movement, is buried here as well as a more elaborate grave site for Bill Fair-weather, which includes a marker that describes him as the discoverer of Alder Gulch.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

The impact on the buildings, and the constant efforts of repair and restoration, is very clear today. Virginia City is far from a sanitized outdoor museum environment. Residents still work and live here, but the historic built environment is in better shape than at any time in the early 1980s, as the images below attest.

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

Save America’s Treasures funding has been leveraged with private donations and state funding to shore up the most significant properties. There is also a much greater, and more accurate, public interpretation found through the historic district. Visitors get much

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

As the image above of the Smith Store attests, there is no need to paint too rosy of a picture about the future of Virginia City. This National Historic Landmark will always need a lot of care, attention, and funding if it is to survive another century. During the national hoopla of the Civil War sesquicentennial in the first half of this decade, the same sesquicentennial of the gold rush to the northern Rockies (Bannock, Virginia City, Helena, etc.) has passed by quietly. But both nation-shaping events happened at the same time, and both deserve serious attention, if we want to stay true to our roots as a nation.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

For travelers along Montana Highway 287 the villages of Laurin and Alder are a mere diversion as you motor along from Sheridan to Virginia City. From those towns the Ruby River winds into the mountains, and they were the “end of the line” for the railroad spur that tied the southern part of Madison County to the state’s rail system. About two miles south of Sheridan is a former late 19th century Queen-Anne style ranch house that now houses the Ruby Valley Inn, a bed and breakfast establishment.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school.

At Laurin, St. Mary of the Assumption Catholic Church is a major Ruby River Valley landmark. It roots the settlement history of this place deep in the valley; John Batiste Laurin, for whom the village is named, established the place in July 1863. The church is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Laurin was never large and a few repurposed commercial buildings indicate that. The historic Laurin School is now a private home, an excellent example of adaptive reuse of a historic rural school. While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students.

While Laurin has a reserved, calm feel to it, Alder feels like the highway road-stop it has been for decades. Its historic brick school is not as architecturally elaborate as Laurin but in 2012 it was still open and serving local students. Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

Other commercial buildings from the early 20th century were now abandoned, including the eye-popping, yellow-painted false front bar and steakhouse, which I understand has moved its business elsewhere since 2012.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

At Alder you can go south on Montana Highway 357 and follow a good, paved road to the Ruby Dam and Reservoir. Part of the New Deal’s contributions to reshaping rural Montana through new or expanded irrigation projects, the Ruby Dam is not an awe-inspiring engineering feat on par with Fort Peck Dam. But the views are striking and here is another engineered landscape created by mid-20th century irrigation projects from the Bureau of Reclamation.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Back on Montana 287 is one of the first log buildings that I visited in Montana, known as Robber’s Roost. Listed in the National Register, this two-story log building dates to 1863, constructed by Pete Daly as a road house for travelers to the Virginia City mines. Tradition has it that it also became a hang-out for road agents who stole from travelers, thus the name. It is an important part of the vernacular log construction tradition of the territorial era in Montana history.

Cutting through Montana’s southeast corner is state highway 287, not a particularly long route at a little over 40 miles in length, but a spectacular one nonetheless as it connects the Madison River Valley (seen above) with the Ruby River Valley, with the famous mining town of Virginia City in the mountains in between.

Cutting through Montana’s southeast corner is state highway 287, not a particularly long route at a little over 40 miles in length, but a spectacular one nonetheless as it connects the Madison River Valley (seen above) with the Ruby River Valley, with the famous mining town of Virginia City in the mountains in between. We have already talked about the western gateway to the highway, the town of Twin Bridges. Now I wish to move from west to east, stopping first Sheridan and its Bethel United Methodist Church, a brick late 19th century Gothic Revival church, which is

We have already talked about the western gateway to the highway, the town of Twin Bridges. Now I wish to move from west to east, stopping first Sheridan and its Bethel United Methodist Church, a brick late 19th century Gothic Revival church, which is

The O’Brien House is also listed in the National Register. Built in 1894, this two-story brick home is another example of Sheridan’s boom following railroad development. It is a rather late example of Italianate style (typically more popular in Montana in the 1870s).

The O’Brien House is also listed in the National Register. Built in 1894, this two-story brick home is another example of Sheridan’s boom following railroad development. It is a rather late example of Italianate style (typically more popular in Montana in the 1870s).

This Craftsman-style building dates c. 1920. Along the street are several interesting examples of domestic architecture from the early 20th century. You wonder if Mill Street might not be a possible National Register historic district.

This Craftsman-style building dates c. 1920. Along the street are several interesting examples of domestic architecture from the early 20th century. You wonder if Mill Street might not be a possible National Register historic district.

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

Montana Highway 41 and the western side of the county is where I start, with the town of Silver Star, nestled between a spur line of the Northern Pacific Railroad, Highway 41, and Jefferson River. Gold was discovered nearby in 1866 and the town is named for a mine, but growth came more from transportation, with Silver Star serving as an early transportation stop between Virginia City and Helena in the 1870s. Today the place is best known for a privately held massive collection of mining machines, tools, and artifacts established by Lloyd Harkins, and for its rural post office that is nestled within the town’s general store.

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933

valley and its irrigation systems helped to produce one of the most famous barns in the state: the Round Barn, just north of Twin Bridges. In 1882 Noah Armstrong, who had made a fortune in mining, built the barn as part of his Doncaster Stable and Stud Farm. In 1933 the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

the Bayers family acquired the barn and incorporated it into their cattle business. When I visited in 1912 the barn was still an agricultural structure, with its wedding cake shape casting a distinct profile on the landscape. In 2015, the barn was restored to a new use: as a wedding and event reception space.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The result is spectacular, and with their restoration in the last 30 years, the buildings are not just landmarks but busy throughout the spring, summer, and fall.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home.

The Old Hotel, a brick two-story gable-front building, also marks the town’s ascent during the early 20th century when the town achieved its highest population, about 750 in 1920. Today about half of that number call Twin Bridges home. My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block.

My personal favorite, and a frequent stop during the 1980s, is the Blue Anchor Bar, nestled on the first floor, with an Art Deco style redesign, in a two-story commercial block. Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.

Twin Bridges is a very important river junction, thus the name, where the Beaverhead, Big Hole, and Ruby rivers all meet to form the Jefferson River. A public park near the confluence just south of the Montana 41/287 helps to tell that story. Nearby is the Twin Bridges School and its amazing modernist styled gymnasium.