The story of the Daly Mansion from a shuttered family owned property in 1984-1985 to a fully realized historic house museum 30 years later also reflects well my timeline of engagement with the historic landscapes of the Big Sky Country. It was a time capsule in the mid-1980s–a house starting to come apart but full of family furniture, papers, and countless treasures. When the house was saved but the interior furnishings sold at auction, it seemed like a permanent separation.

My first post on this blog in 2013 about the Daly Mansion and its restoration lauded the determination of the local non-profit to finish the exterior renovation and repairs, and to have the place open to the public on a regular basis. It was and is an impressive achievement in a time when so-called experts say the era of historic house museums is over. But it was very much an exterior tour–when I visited six years ago, photographs were not allowed, not so much to protect items but because so much remained to be done. The place just did not have a historic “lived in” look.

In the last five years, the Daly Mansion board and its many local supporters have finished the job. Key pieces of family furniture, like the settee above and much of the dining room below, have returned, due in large part to purchases and commitments made at the original auction in the 1980s but many objects coming back to the house due to the persistence of board members and the willingness of auction buyers to return items now that 30 years have passed.

The result is a house museum that depicts well the life of a wealthy family on their version of the 20th century country estate, and now with an appropriate focus on Margaret Daly, who selected the architectural style, purchased many of the furnishings, and kept the estate forefront in Montana luxury for four decades (Marcus Daly died in 1900, before the Colonial Revival conversion of the original house; Margaret lived until 1941). Margaret Daly’s bedroom furniture had long been in the collections of the University of Montana Library–they are now in their rightful place in the Daly Mansion.

The lushness, and personality, of Margaret Daly’s private quarters is now the norm across the house, from the first floor parlor to the second floor setting room.

Even the third floor ballroom, once an evocative but largely empty space, is now used to display and interpret the rather amazing clothing collections of the museum.

Certainly the words of one visitor during my May 2018 ring true: “they were rich but had little taste” in the decorative arts. But for Margaret Daly her Riverside estate was not a showplace as much as a place to escape for the summer. The hodge-lodge of trendy but individually undistinguished furniture and objects suited that purpose just fine.

The Daly Mansion is at a new place–a preservation and restoration project that had stretched out for thirty years. But now the interior story, especially the focus on Margaret Daly, steps up to center stage. The meaning of Riverside and the Bitter Root Stock Farm is still waiting for a full exploration and analysis.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Here is a property category that could be, probably should be, a blog of its own–the ranching landscape of Big Sky Country. Historic family ranches are everywhere in the state, and being of rural roots myself, and a Tennessee Century Farm owner, the ways families have crafted their lives and livelihood out of the land and its resources is always of interest.

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

Preserving merely the ranch house, and adding other period buildings, is one thing. The massive preserved landscape of hundreds of acres of the Grant-Kohrs Ranch in the western end of Montana is a totally different experience. This National Park Service site

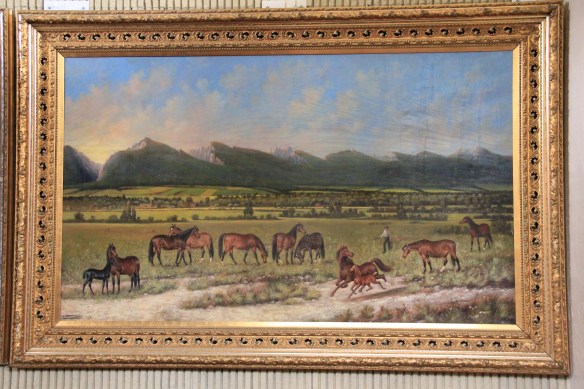

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

The Bitter Root Stock Farm, established in 1886 by soon-to-be copper magnate Marcus Daly outside of Hamilton, came first. I can recall early site visits in 1985–that started the ball rolling but the deal wasn’t finalized for several years. All of the work was worth it.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

first glance, architecturally magnificent as the properties above. But in its use of local materials–the timber, the rocks from the river bluffs–and its setting along a historic road, this ranch is far more typical of the Montana experience.

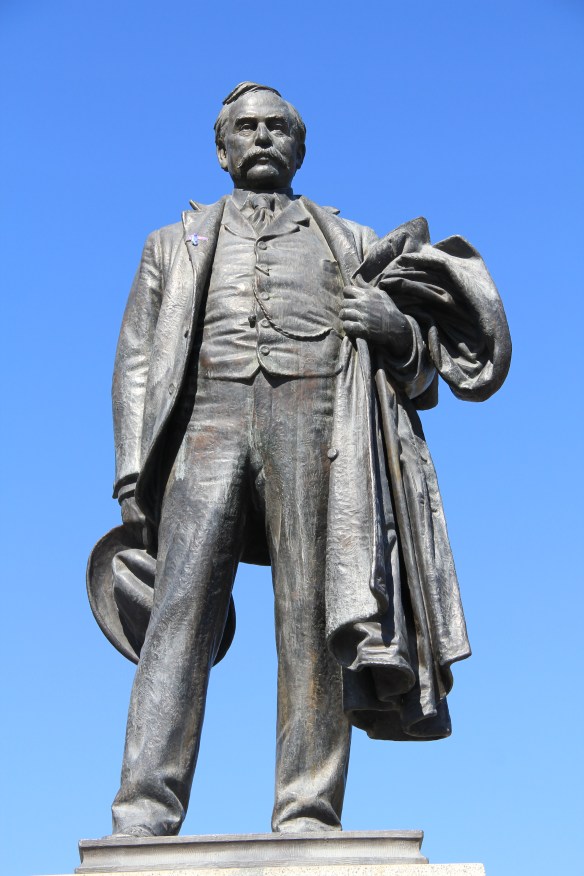

Marcus Daly, the copper magnate of Butte and Anaconda, certainly put his stamp on the landscape of Silver Bow and Deer Lodge counties. But not until the early 1980s did most Montanans understand that Daly too had shaped the landscape of the Bitterroot Valley with the creation and expansion of his Bitterroot Stock Farm, starting in 1886 and continuing even beyond his death in 1900.

Marcus Daly, the copper magnate of Butte and Anaconda, certainly put his stamp on the landscape of Silver Bow and Deer Lodge counties. But not until the early 1980s did most Montanans understand that Daly too had shaped the landscape of the Bitterroot Valley with the creation and expansion of his Bitterroot Stock Farm, starting in 1886 and continuing even beyond his death in 1900.

to have a place, on the other side of the divide from his dark, dank, smelly mining towns, where he and his family could escape and enjoy Montana’s open lands and skies. The ranch began with the purchase of the Chaffin family homestead in 1886. Daly immediately set forth to remodel and expand the older ranchhouse yet those changes only lasted three years when Daly replaced the first house with a rather grand and flamboyant Queen Anne-styled mansion and named it Riverside. Daly died in 1900 and Riverside’s last grand remodeling was guided by his wife, who looked to architect A. J. Gibson of Missoula to design a Colonial Revival-on-steroids mansion, which referenced the recent Roosevelt family mansion on the Hudson River in New York State.

to have a place, on the other side of the divide from his dark, dank, smelly mining towns, where he and his family could escape and enjoy Montana’s open lands and skies. The ranch began with the purchase of the Chaffin family homestead in 1886. Daly immediately set forth to remodel and expand the older ranchhouse yet those changes only lasted three years when Daly replaced the first house with a rather grand and flamboyant Queen Anne-styled mansion and named it Riverside. Daly died in 1900 and Riverside’s last grand remodeling was guided by his wife, who looked to architect A. J. Gibson of Missoula to design a Colonial Revival-on-steroids mansion, which referenced the recent Roosevelt family mansion on the Hudson River in New York State.

There is really nothing in the world of domestic architecture in Montana to compare to the Daly family’s Riverside estate. As we made our plans for the state historic preservation survey in 1984, I never imagined gaining access to this mysterious place. Then, suddenly, the owners decided to offer the property to someone–the state preferably but locals if necessary–who could transform it into a historic house museum and still working farm.

There is really nothing in the world of domestic architecture in Montana to compare to the Daly family’s Riverside estate. As we made our plans for the state historic preservation survey in 1984, I never imagined gaining access to this mysterious place. Then, suddenly, the owners decided to offer the property to someone–the state preferably but locals if necessary–who could transform it into a historic house museum and still working farm.

Indeed not far away is a 21st century sign of the super-rich and their imprint on the Montana landscape: the Stock Farm Club, a private, gated community for those who can afford it–and probably 99% cannot.

Indeed not far away is a 21st century sign of the super-rich and their imprint on the Montana landscape: the Stock Farm Club, a private, gated community for those who can afford it–and probably 99% cannot.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation.

Many heritage areas in the eastern United States emphasize the relationship between rivers, railroads, and industrial development and how those resources contributed to national economic growth and wartime mobilization. Great Falls can do that too. Situated on the Missouri River and designed by its founders to be a northwest industrial center, entrepreneurs counted on the falls to be a source of power and then on the railroads coming from Minnesota, especially the promising Manitoba Road headed by James J. Hill, to provide the transportation. Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

Paris Gibson, the promoter of the Electric City, allied his interests to two of most powerful capitalists of the region: Marcus Daly, the baron of the Anaconda Copper Company interests and James J. Hill, the future rail king of the northwest. Their alliance is embodied in several different properties in the city but the most significant place was where the Anaconda Copper Company smelter operated at Black Eagle until the last decades of the 20th century. When I surveyed Great Falls for the state

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others

decade of the 20th century and soon erected its tall tower depot right on the Missouri River. But wherever you go along the river you find significant buildings associated with the Great Northern and its allied branch the Montana Central Railroad, especially the downtown warehouses. Some are still fulfilling their original function but others