Far from the bustle and grime of the Richest Hill on Earth are the historic cemeteries of Butte. As I have said many times already in this blog, I rarely considered cemeteries during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. That was a huge mistake for Butte. The three historic cemeteries I wish to consider here–Mt. Moriah, St. Patrick’s, and B’nai Israel–document the city’s ethnic diversity like few other resources, reinforcing how groups survived in a city together although they often keep to their separate communities. But the cemeteries also have sculpture and art worthy of attention and preservation–they are outstanding examples of late 19th and early 20th cemetery art and craftsmanship in the United States.

Far from the bustle and grime of the Richest Hill on Earth are the historic cemeteries of Butte. As I have said many times already in this blog, I rarely considered cemeteries during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. That was a huge mistake for Butte. The three historic cemeteries I wish to consider here–Mt. Moriah, St. Patrick’s, and B’nai Israel–document the city’s ethnic diversity like few other resources, reinforcing how groups survived in a city together although they often keep to their separate communities. But the cemeteries also have sculpture and art worthy of attention and preservation–they are outstanding examples of late 19th and early 20th cemetery art and craftsmanship in the United States.

The Masons established Mr. Moriah Cemetery Association in 1877. The cemetery has many striking markers, especially the Thompson Arches (seen above and below), an elaborate statement to mark a family plot, especially when compared to the cast-iron

The Masons established Mr. Moriah Cemetery Association in 1877. The cemetery has many striking markers, especially the Thompson Arches (seen above and below), an elaborate statement to mark a family plot, especially when compared to the cast-iron

fences found elsewhere in the cemetery, like for the Nicholls family. The Victorian cast

iron fence, when combined with the carving and detail of the gravestone itself makes quite the statement for Cornish identity in Butte at the turn of the century. Note the dual fraternal lodge marks, one for the Masons, another (the linked chain) for the Odd Fellows.

iron fence, when combined with the carving and detail of the gravestone itself makes quite the statement for Cornish identity in Butte at the turn of the century. Note the dual fraternal lodge marks, one for the Masons, another (the linked chain) for the Odd Fellows.

Frank Beck left this earth in 1909, and the marker for Frank and his wife Agnes is remarkable for the inclusion of the family pet, noted above as Frank and His Faithful Dog.

Frank Beck left this earth in 1909, and the marker for Frank and his wife Agnes is remarkable for the inclusion of the family pet, noted above as Frank and His Faithful Dog.

The early 20th century gravestones and family plots are impressive largely wherever you ramble in Mt. Moriah Cemetery, and I am limiting my comments to merely a few markers. But you cannot help but notice the family gravestone, sculpture actually, for the Noyes family, a large neoclassical setting with the motif “The Day Break and the Shadows Flee Away,” framed by two large metal angels holding wreaths.

Not everything in Mt. Moriah is so spectacular, but the evidence of the skill and creativity of Butte’s gravestone makers can be found throughout the property.

B’nai Israel Cemetery is small in comparison yet it is a valuable space that documents the Jewish community’s long history in Butte. It is not quite as early as Mt. Moriah, dating to

1881 when the Hebrew Benevolent Association first acquired the land from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Congregation B’nai Israel acquired the property in 1905, two years after finishing its landmark synagogue in uptown Butte.

1881 when the Hebrew Benevolent Association first acquired the land from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Congregation B’nai Israel acquired the property in 1905, two years after finishing its landmark synagogue in uptown Butte.

St. Patrick Catholic Cemetery is also located in this part of the city. It dates to the 1870s and contains thousands of burials. When I visited in 2012 the cemetery was in OK condition but needed help, not just in basic maintenance but in the repair of tombstone damaged over the decades. Just about a year ago in a story in the Montana Standard of March 1, 2015, members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians, a Irish Catholic fraternal group, pledged new efforts for the cemetery’s preservation: “‘A walk around this holy ground will tell you more about the people of Butte than a week spent at the library,’ said Jim Sullivan, one of 60 members of the Ancient Order of Hibernians in Butte.”

The cemetery seems to stretch to the very edge of the city, but it is worth a long walk around for what you can discover about the Catholic impact on Butte in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The cemetery seems to stretch to the very edge of the city, but it is worth a long walk around for what you can discover about the Catholic impact on Butte in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

There are spectacular sculptural monuments to prominent city builders, such as the Classical Revival-style temple crypt for merchant price D. J. Hennessy.

There are spectacular sculptural monuments to prominent city builders, such as the Classical Revival-style temple crypt for merchant price D. J. Hennessy.

Adjacent are separate plots maintained for Sisters who served and died in Butte as well as larger, more elaborate memorials for priests who served in Butte over the years.

Adjacent are separate plots maintained for Sisters who served and died in Butte as well as larger, more elaborate memorials for priests who served in Butte over the years.

A surprise near the rear of the cemetery is a large memorial section for military veterans of the Spanish-American War of the late 1890s. This conflict is often ignored in today’s history books but numerous cemeteries in Montana have memorial sections for those who fought and died in that war.

The dominant grave marker at St. Patrick’s is a small stone tablet but cemetery sculpture emphasizing the cross can be found throughout the property.

Then there are a handful of sculptural markers with an angel theme, and these are among the most spectacular in the cemetery. The Daly marker (below) is an elegant, moving

statement of loss and sorrow. The O’Farrell monument (below) likewise conveys sorrow and loss in the combination of an angel and the cross but by including a relief carving of O’Farrell it also serves as a very public memorial for a prominent family member.

Throughout this brief exploration of three historic cemeteries, I have deliberately left the stories associated with this remarkable cemetery art to the side. A few years ago, in 2010, local historian Zena Beth McGlashan published her book “Buried in Butte.” I wished the book had existed in 1985–maybe then I would not have ignored one of the most fascinating and significant sections of Butte: its three adjacent historic cemeteries along South Montana Street. Next, an exploration of Mountain View Cemetery.

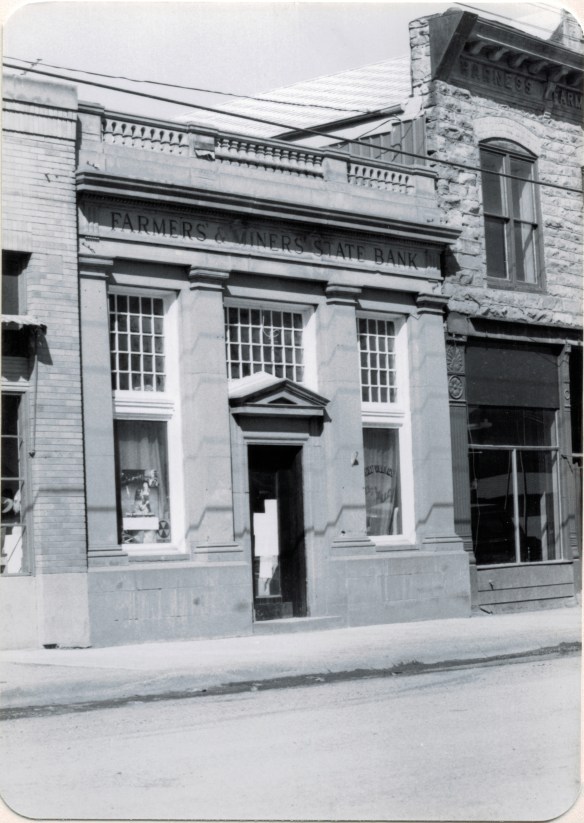

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

Let me just jump right in: I do not know of another town in Montana that has done more with the concept of heritage development than Butte in the last 30 years. Heritage development, in brief, means that a community identifies the stories and places that define their past and sense of identity and then uses them as tools for community revitalization and growth. The stories and places must be authentic, meaningful, real–fake pasts don’t get you very far. In 1981, out of fears that its storied and nationally significant history would be lost in the haze of late 20th century urban renewal and economic change, Butte created as part of local government the Butte-Silver Bow Archives–everyone I knew were excited about its potential and its early discoveries at the time of the state historic preservation plan work in 1984-1985. Now that institution is one of the key rocks upon which Butte’s future lays. Above is the conversion of a historic firehall into the modern archives/heritage center the institution is today–in itself a great example of adaptive reuse and historic preservation at work.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

a vibrant institution, always in touch as its community room hosts other heritage groups and special programs throughout the year. The archives is just around the corner from one of the most important, and solemn, places in the city, the location of the Butte Miners’ Union Hall, which was bombed in 1914.

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

Heritage development has become part of the basic sinews of Butte. Along with its active archives board, the city also maintains an effective historic district commission, and provided seed money for several key projects over the past generation. The Original Mine site below, the city’s first copper mine, not only serves as part of the city’s public

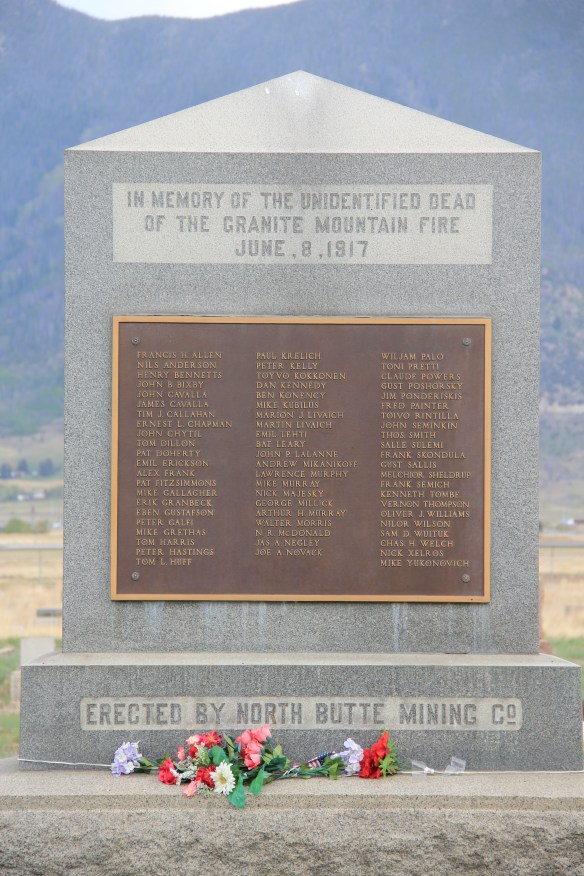

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

Today the Granite Mountain site is one of the best interpreted mining properties I have encountered. The miners’ stories are told–often with the words they were able to write down before dying from the lack of oxygen–and their multiple ethnic backgrounds are acknowledged, and celebrated.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

The interpretive memorial overlooks the mine, and is located high over town. But when I visited in May 2012 a school group was there too, along with visitors like me.

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the

All of these efforts considerably enhance earlier efforts at public interpretation, be they along Interstate I-15 and its overview of Butte or the visitor center maintained just off the interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot.

interstate by the local chamber of commerce. The center, yet another change in the last 30 years, is an attractive reproduction of a classic railroad depot design. It also provides a useful perspective of the city from its south side, giving special prominence to the soaring clock tower of the historic Milwaukee Road depot. The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

The Berkeley Pit in 1984 was a giant hole in the earth, with a viewing stand. It too now has a more comprehensive heritage experience with a small visitor center/ museum adding to the public understanding of the massiveness and significance of the pit.

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

Butte–the copper city that was once the largest urban area in Montana–was a place undergoing tremendous stress at the time of state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985. The closing of the Berkeley Pit–the most scarred landscape of that time in Montana (the coal pits of Colstrip now surpass it)–shocked so many since Anaconda

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation.

From here you understood that Uptown–the state’s most sophisticated urban setting–was little more than a speck within a larger landscape where people lived and toiled, scratching out lives for their families, building communities, providing raw materials to a hungry industrial world. But what seemed to me to be the vastness of Butte was actually a decidedly human response to the far greater vastness of the northern Rockies. Here was a landscape of work like few others in this nation. There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible.

There are few better places in the United States to explore the landscape of work, and how opportunity attracted all types of people from all sorts of lands to mine the copper, to house the workers, to feed the families, to provide rest and relaxation, to do all of things big and small it takes to keep a place humming 24 hours a day for decades, taking from the earth materials that made modern suburban America possible. I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

I cannot touch upon everything or everyone that define the Butte experience today but in the next several posts I want to dig deep into this landscape and discuss how this transformed place is now, for me, the most compelling spot of all in Montana.

Along the Missouri River is Paris Gibson Park, deep in the heart of Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was one of the classic civic capitalists of the late 19th century who understood that as the community prospered he too would achieve this dream of building a great western empire, with his town of Great Falls as the center. Almost 100 years after his death, in 2015, residents, preservationists, historians, and economic developers began discussions on establishing a heritage area, centered on Great Falls, but encompassing the Missouri River as the thread between the plains and mountains, that has shaped the region, and the nation, for hundreds of years. I strongly endorse the discussion and will spend the next several posts exploring key resources in Cascade County that could serve as the foundation for a larger regional story.

Along the Missouri River is Paris Gibson Park, deep in the heart of Great Falls, Montana. Gibson was one of the classic civic capitalists of the late 19th century who understood that as the community prospered he too would achieve this dream of building a great western empire, with his town of Great Falls as the center. Almost 100 years after his death, in 2015, residents, preservationists, historians, and economic developers began discussions on establishing a heritage area, centered on Great Falls, but encompassing the Missouri River as the thread between the plains and mountains, that has shaped the region, and the nation, for hundreds of years. I strongly endorse the discussion and will spend the next several posts exploring key resources in Cascade County that could serve as the foundation for a larger regional story.

Thirty years later, Belt’s population had bottomed out, declining to under 600 by the time of the 2010 census. But both times I have stopped by, in 2013 and 2015, the town has a sense of life about it, and hope. The town’s two historic taverns, the Harvest Moon Tavern and the Belt Creek Brew Pub, as well as the Black Diamond Bar and Supper Club attract visitors from nearby Great Falls and elsewhere, giving the place a sense of life at evenings and weekends.

Thirty years later, Belt’s population had bottomed out, declining to under 600 by the time of the 2010 census. But both times I have stopped by, in 2013 and 2015, the town has a sense of life about it, and hope. The town’s two historic taverns, the Harvest Moon Tavern and the Belt Creek Brew Pub, as well as the Black Diamond Bar and Supper Club attract visitors from nearby Great Falls and elsewhere, giving the place a sense of life at evenings and weekends.

When planners talk about heritage areas, they often focus on the contributions of local entrepreneurs who take historic buildings, like the Pioneer above, and breathe new life into them. Throughout small town Montana and urban commercial districts, new breweries and distilleries are creating such opportunities.

When planners talk about heritage areas, they often focus on the contributions of local entrepreneurs who take historic buildings, like the Pioneer above, and breathe new life into them. Throughout small town Montana and urban commercial districts, new breweries and distilleries are creating such opportunities.

Belt has a range of historic buildings, mostly of vernacular two-part commercial style that speak strongly to the boom of 1900 to 1920. The Victorian-styled cornice of the Belt Hardware Store (1896) speaks to the town’s origins. The Knights of Pythias Lodge of 1916 has been restored as a community theater, another reason for visitors to stop and explore.

Belt has a range of historic buildings, mostly of vernacular two-part commercial style that speak strongly to the boom of 1900 to 1920. The Victorian-styled cornice of the Belt Hardware Store (1896) speaks to the town’s origins. The Knights of Pythias Lodge of 1916 has been restored as a community theater, another reason for visitors to stop and explore. The result is a living cultural experience, since nothing in Belt is over-restored or phony feeling. It is still a gritty, no frills place. That feel is complemented by the Belt museum, which is housed in a historic jail on road down into town and within sight on a railroad trestle, a reminder of what literally drove the town’s development, coal for the railroads.

The result is a living cultural experience, since nothing in Belt is over-restored or phony feeling. It is still a gritty, no frills place. That feel is complemented by the Belt museum, which is housed in a historic jail on road down into town and within sight on a railroad trestle, a reminder of what literally drove the town’s development, coal for the railroads. During the 1984 survey, I gave the jail a good bit of attention since this stone building spoke to the craftsmanship of the era, the centrality of local government as the town developed, and the reality that this building was the only thing in Belt listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But in 2004 the state historic preservation office approved the Belt commercial historic district, and that designation has done much to drive the town’s recent revival. Belt is just the first place that speaks to the promise of the Great Falls heritage area concept.

During the 1984 survey, I gave the jail a good bit of attention since this stone building spoke to the craftsmanship of the era, the centrality of local government as the town developed, and the reality that this building was the only thing in Belt listed in the National Register of Historic Places. But in 2004 the state historic preservation office approved the Belt commercial historic district, and that designation has done much to drive the town’s recent revival. Belt is just the first place that speaks to the promise of the Great Falls heritage area concept.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town.

Even the local museum was at the beginning stage, sharing quarters with the chamber of commerce in a Ranch-style building, like the park, on the outskirts of town. How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history.

How times changed over 30 years. The museum is still at its location but adjacent is now a new facility, replicating a huge barn, expanded exhibits and artifacts about the region’s history. Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society.

Markers about National Register-listed properties and districts exist throughout town, courtesy of the exemplary interpretive marker program of the Montana Historical Society. What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense.

What happens within town is supported by recent interpretive marker installations at the highway rest stop as you enter Lewistown. From this spot there is an excellent view of the historic Lewistown airfield, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, for its significance in World War II aerial supply lines and defense. Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation.

Not only can you see the historic district, you also can learn about its significance through an interpretive marker developed by Montana Department of Transportation. Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Steps away is another interpretive kiosk, related to an earlier, sadder military story, that of Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians and their attempted flight to freedom in Canada in the 1870s. Both markers also emphasized the overall theme of transportation and how Lewistown has been crisscrossed by important historical events for centuries.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods.

Renaissance revival style from the prominent Montana firm of Link and Haire, and the historic early 20th century domestic architecture in the downtown neighborhoods. The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and

The town’s historic districts serve as anchors within the commendable trail system developed in Lewistown over the last 20 years. Local officials and representatives, working with the state government and abandoned railroad property and corridors, have established a series of trail loops that not only provide excellent recreational opportunities, as signified in this trail head near the Yogo Inn, but also paths for heritage tourists and residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today.

residents alike to explore the landscape, and how history in the 19th and 20th centuries created the place where they live and play today. As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis.

As we will see later in western Montana, like in Butte and Kalispell, trail systems can be the best of heritage development because they take advantage of the state’s greatest asset–its landscape and sense of the Big Sky Country–and combine it with explanations of the layers of history you encounter wherever you go, creating an asset that visitors will like but that residents will cherish, because they can use it on a daily basis. Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Of course recreation, to my mind, is never complete unless there are nearby watering holes where one can relax and replenish, and Lewistown is rich in those too, being they the various classic roadside establishments along the highways entering and leaving town or the can’t miss taverns downtown, such as The Mint and the Montana Tavern, where the signs speak to the good times to come. Those properties are crucial for heritage development because they are important in themselves but they also are the places that get people to stop, and hopefully explore.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.

Using multiple pasts to create new opportunities for communities: Lewistown has it going, and it’s far different world today than in 1984.