Kalispell is the seat of Flathead County, established on the Great Northern Railroad line in the 1890s. Today the city is the hub for commerce, transportation and medical care in northwest Montana. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation designated it as a Preserve America community in recognition of its historic downtown and multiple National Register of Historic Places properties.

Certainly the town has many impressive late Victorian era buildings, like the County Courthouse, but this post focuses on a part of Kalispell’s historic built environment that doesn’t get enough attention—its buildings of modern 20th century styles.

The key town founder was C. E. Conrad and similar to how he started the town, you could also say he started the modernist traditions by commissioning his grand Shingle-style mansion from architect A.J.Gibson in 1895. Architectural historians consider the Shingle style, introduced by major American architects Henry Hobson Richardson and the New York Firm McKim, Mead, and White, to be an important precursor to the modernist buildings that would flourish in Kalispell during the 1930s.

Another important example of early modernist style is this local adaptation of Prairie house style, a form introduced and popularized by the designs of American master Frank Lloyd Wright.

Kalispell’s best modernist examples come from the 1930s to 1960s. In 1931 Brinkman designed the KCFW-TV building in a striking Art Deco style. It was originally a gas station but has been restored as an office building with its landmark tower intact.

The Strand Theatre closed as a movie house in 2007 but its colorful Art Deco marquee and facade remain, another landmark across the street from the History Museum which is housed in the old high school.

The Eagles Lodge (1948-1949) is an impressive example of late Art Deco style, especially influenced by the federal “WPA Moderne” buildings from the New Deal. G.D. Weed was the architect.

Then the town opened Elrod School in 1951. It is a good example of mid-century International style in a public building.

The 1950s decade witnessed new modern style religious buildings. The Central Bible Church (1953) evolved from a merger of Central Bible and the West Side Norwegian Methodist Church. Harry Schmautz was the architect.

That same year, the Lutheran church added a new wing for its youth ministry, the Hjortland Memorial, which is one of Kalispell’s most impressive 1950s design. Ray Thone was the architect.

In 1958 Central Christian Church completely remodeled its earlier 1908 building to a striking modern design.

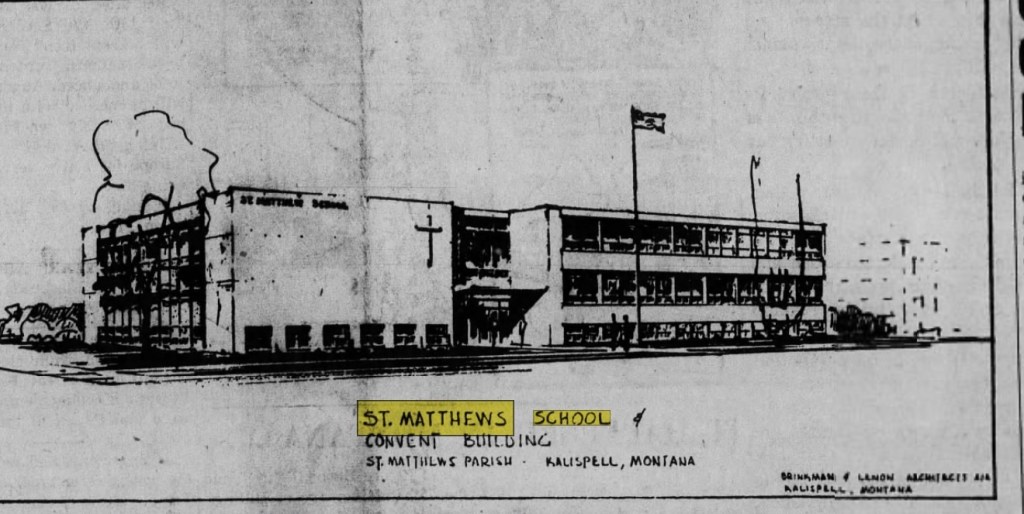

That same year came the opening of St. Matthew Catholic School, an impressive two-story example of International style in an institutional building. the architect was the firm of Brinkman and Lenon.

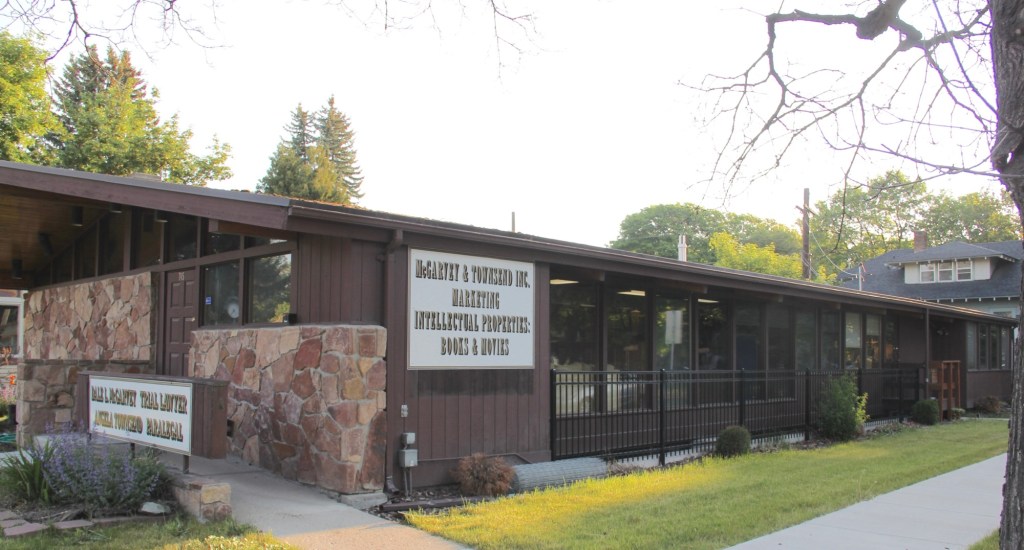

Kalispell also has two excellent examples of commercial buildings in the mid-century contemporary style. Below is the stone veneer and window wall of the McGarvey and Townsend building.

But my favorite, until a recent “remuddling,” is the Sutherland Dry Cleaners, now a golf supply shop.

Kalispell has several good examples of mid-century domestic design. My favorite is this Ranch-style residence near the Conrad Mandion.

This post doesn’t include all of Kalispell’s modernist designs but hopefully I have included enough to demonstrate that the town has a significant modernist architecture tradition.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950.

In the early posts of this exploration of Montana’s historic landscape I spoke of the transformation that I encountered when I revisited Glendive, the seat of Dawson County, for the first time in about 25 years, of how local preservation efforts had kept most of the town’s railroad era landscapes alive while leading to the revitalization of its amazing number of historic residences from 1900 to 1950. Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural

Let’s now turn our attention to public landmarks, old and more recent, that also deserve notice, starting with the magnificent Classical Revival-styled City Hall, one of the anchors of the Merrill Avenue historic district, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. Built in 1914, this all-in-one municipal building is an impressive architectural statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City.

statement by the second generation of Glendale’s leaders that the town would grow and prosper during the homesteading boom of the first two decades of the 20th century. The architect was Brynjulf Rivenes of Miles City. His firm had so many commissions coming from eastern Montana and Yellowstone Valley patrons that by this time Rivenes operated offices in both Glendive and Miles City. Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

Rivenes had earlier marked Glendive’s new emerging townscape with his Gothic design for the First Methodist Church, in 1909. Fifteen years later, he added another landmark church design with the Romanesque styled Sacred Heart Catholic Church (1924-1925).

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

With recovery and the arrival of more and more automobile traffic from the late 1930s to the 1950s, many of the older buildings received mid-century updates. The remodels could

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

The 1950s and 1960s brought many changes to Glendive. Post World War Ii growth both in the town and the many surrounding ranches led to expansion and remodeling at the historic Glendive Milling Company in 1955. When the historic districts for Glendive were designated in the late 1980s, preservationists questioned the inclusion of this important industrial/agricultural complex due to the changes of the 1950s. Viewed today, however, the mill complex is clearly a very significant historic site.

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at

More contemporary styled church buildings were also dedicated in the mid-century, such as the classic “contemporary” styling of the Assembly of God building, with classrooms at at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive.

at the front rather than the rear, or the modified A-frame style of the First Congregational Church, which I shared in an earlier post on Glendive. Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor

Glendive is very much a blending of different 20th century architectural styles, reaching back into the region’s deep, deep past, as at Makoshika State Park, where the visitor center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

center/museum is an excellent example of late 20th century modern style–clearly a building of the present but one that complements, not overwhelms, the beauty of the park itself.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.

The images above and those below come from those well maintained neighborhoods, where the sense of place and pride is so strongly stated.

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment.

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment. The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

But in the last 30 years, Polson has boomed as a lakeside resort town, with a population of 4700 today compared to the 2800 of the 1980s. Key landmarks remain but nothing has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since my 1984 visit, even the great New Deal modern courthouse above.

But in the last 30 years, Polson has boomed as a lakeside resort town, with a population of 4700 today compared to the 2800 of the 1980s. Key landmarks remain but nothing has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places since my 1984 visit, even the great New Deal modern courthouse above.

These landmarks need to be treasured because a new Polson is emerging all around town–and could crowd out the places that frame the community’s identity. Right now there is a balance between old and new, but a tipping point is around the corner.

These landmarks need to be treasured because a new Polson is emerging all around town–and could crowd out the places that frame the community’s identity. Right now there is a balance between old and new, but a tipping point is around the corner.

South 3rd Street also has a strong set of bungalows, Montana style, which means that they take all sorts of forms and use all sorts of building materials.

South 3rd Street also has a strong set of bungalows, Montana style, which means that they take all sorts of forms and use all sorts of building materials.

My favorite set of public buildings in Hamilton got back to the theme of town and ranch and how community institutions can link both. The Ravalli County Fairgrounds began on

My favorite set of public buildings in Hamilton got back to the theme of town and ranch and how community institutions can link both. The Ravalli County Fairgrounds began on 40 acres located south of downtown on the original road to Corvallis in 1913. Its remarkable set of buildings date from those early years into the present, and the Labor Day Rodeo is still one of the region’s best.

40 acres located south of downtown on the original road to Corvallis in 1913. Its remarkable set of buildings date from those early years into the present, and the Labor Day Rodeo is still one of the region’s best.

You don’t think Montana modernism when you think of Butte, but as this overview will demonstrate, you should think about it. I have already pinpointed contemporary homes on Ophir Street (above). The copper mines remained in high production during the Cold War era and many key resources remain to document that time in the city. For discussion sake, I will introduce some of my favorites.

You don’t think Montana modernism when you think of Butte, but as this overview will demonstrate, you should think about it. I have already pinpointed contemporary homes on Ophir Street (above). The copper mines remained in high production during the Cold War era and many key resources remain to document that time in the city. For discussion sake, I will introduce some of my favorites.

I looked at schools constantly across the state in 1984-1985 but did not give enough attention to the late 1930s Butte High School, a classic bit of New Deal design combining International and Deco styles in red brick. Nor did I pay attention to the modernist buildings associated with Butte Central (Catholic) High School.

I looked at schools constantly across the state in 1984-1985 but did not give enough attention to the late 1930s Butte High School, a classic bit of New Deal design combining International and Deco styles in red brick. Nor did I pay attention to the modernist buildings associated with Butte Central (Catholic) High School.

You would think that I would have paid attention to the Walker-Garfield School since I stopped in at the nearby Bonanza Freeze, not once but twice in the Butte work of 1984. I

You would think that I would have paid attention to the Walker-Garfield School since I stopped in at the nearby Bonanza Freeze, not once but twice in the Butte work of 1984. I never gave a thought about recording this classic bit of roadside architecture either. Same too for Muzz and Stan’s Freeway Bar, although maybe I should not recount the number of stops at this classic liquor-to-go spot.

never gave a thought about recording this classic bit of roadside architecture either. Same too for Muzz and Stan’s Freeway Bar, although maybe I should not recount the number of stops at this classic liquor-to-go spot.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana.

for places to rest, relax, and enjoy the precious hours away from the workplace. So much has changed in Anaconda since the closing of the smelter in the early 1980s–but the town’s distinctive places for recreation and relaxation remain, a big part of the reason Anaconda is one of my favorite places in Montana. Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

Let’s start with the magnificent Art Deco marvel of the Washoe Theater. Designed in 1930 by B. Marcus Priteca but not finished and opened until 1936, the theater has stayed in operation ever since. It is remarkably intact, especially when owners refused to follow the multi-screen craze of the 1970s and kept the lobby and massive screen

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

A drink after the movie: still happens with regularity in Anaconda, due to the plethora of neighborhood bars, from the Anaconda Bar to the Thompson Bar. The range of sizes and styling speaks to the different experiences offered by these properties.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

The Elks Club in the heart of downtown is a totally different statement, with its sleek 1960s modernist facade over an earlier turn of the century Victorian styled brick building reflecting a more prosperous and larger membership.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

With its glass block entrances and windows, the American Legion lodge seems like another lounge, but the American Eagle mural says otherwise.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

If not bowling, why not read a book. At least that was the motivation behind Progressive reformers and their initiative to create “free” (meaning no membership fees) public libraries at the turn of the 20th century. Anaconda has one of the state’s earliest and most architecturally distinctive libraries in the Hearst Free Library.

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

Another Progressive-era institution is Washoe Park, established by the copper company and home to the first fish hatchery in the state. Washoe Park was a place for outdoor recreation, with ball fields, picnic areas, and amusement attractions. It also was home for the town’s baseball field and its historic grandstands and refreshment

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920.

New renovations at the park have been underway, improving trails, the hatchery, and the outdoor experience plus adding public interpretation at appropriate places. The park is being re-energized but respect still shown its early elements, such as the historic Alexander Glover cabin, built c. 1865 and identified as the oldest residence in Anaconda, which was moved into the park as an interpretive site, early, c. 1920. Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling.

Another outdoor recreational space that has been receiving renovation is the historic Mitchell Stadium complex, a New Deal project of the Works Progress Administration from 1938-1939. The stadium, designed to give the high school modern facilities for football and track and field, is quite the place, retaining so much of its original understated Art Deco styling. Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

Unlike Washoe Park, here was a new public space, in keeping with the New Dealers’ faith in recreation and community, that was not a creation of the copper company for adult workers but for high school athletes.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda.

But even on the links of this innovative adaptive reuse project you cannot escape the overwhelming presence of the copper company stack, and mounds of devastation it left behind. Here is an appropriate view that sums up the company influence on the distinctive place of Anaconda.