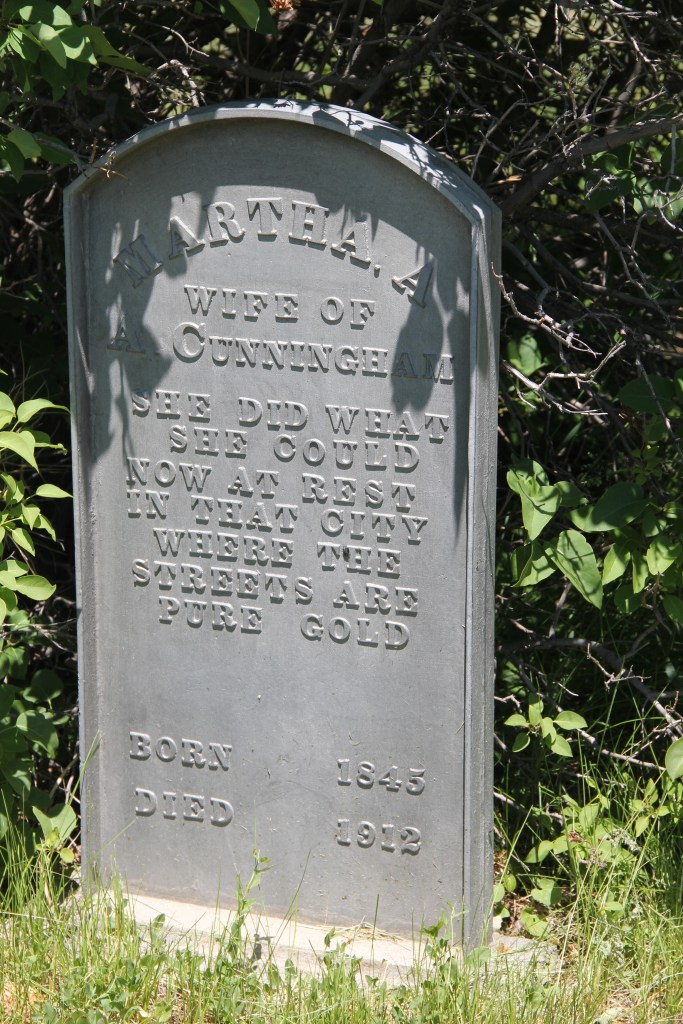

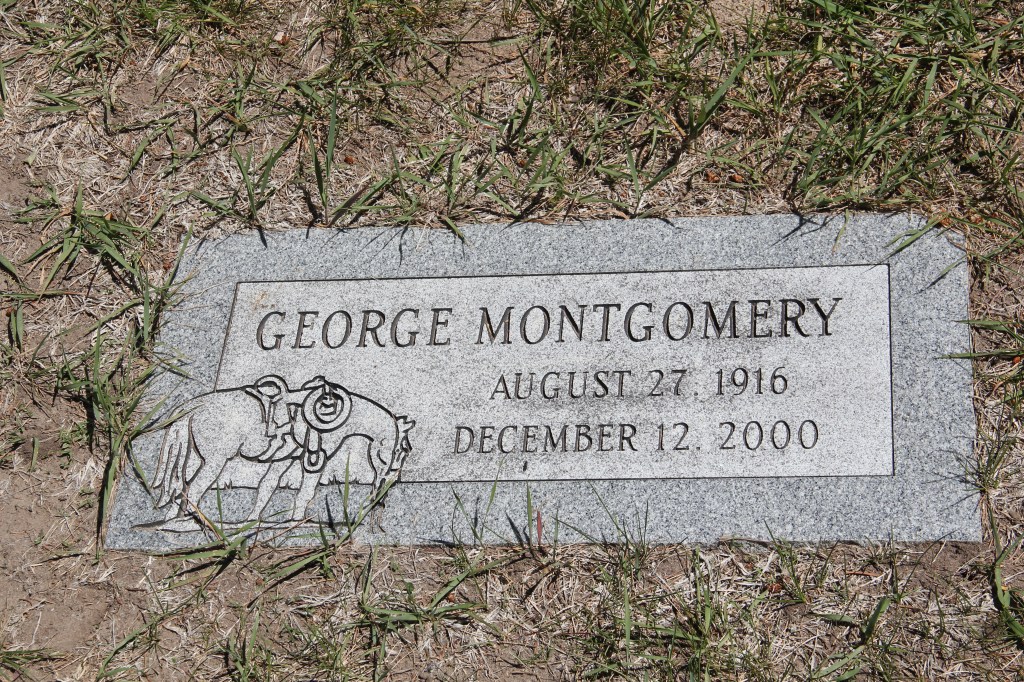

Due to considerable interest from readers of this blog, I planned a second visit to Mountain View Cemetery in May 2023. Perhaps best known nationally as the final resting place for stuntman and daredevil Evel Knievel, I discovered in my first visit the rich and informative ethic handprint on the place. The cemetery is an excellent property to explore Butte’s ethnic history, and I want to explore more of that in a later posting.

This post, however, aims to explore concerns about the southern half of Mountain View cemetery, and how a lack of irrigation and upkeep have left hundreds of graves in poor repair and in danger of headstones or burial names and locations being lost forever.

Historians of the labor movement in Butte should be concerned because the southern section is also the final resting place for Frank Little, one of the most important individuals associated with the IWW during World War I.

Admirers of Little and later labor activists have insured that his gravesite is not lost. judging from Little’s words and deeds, however, you wonder if he would not be concerned that while his grave is preserved those of his fellow miners and citizens buried around him are neglected.

Maintaining historic cemeteries is a challenge as we have seen in many places, not just across Montana but the entire nation. In tough times with many demands for services and support, what is the priority for cemetery maintenance compared to other pressing community needs, like schools and public safety? I wish I had instant answers—but I think I know where you start: by recognizing the problem and then having discussions and more discussions to find community solutions.