For sheer scale and audacity nothing in Montana built environment rivals the transformations wrought on the Missouri River and the peoples who for centuries had taken nourishment from it than the construction of Fort Peck Dam, spillway, powerhouse, reservoir, and a new federally inspired town from the 1930s to the early 1940s.

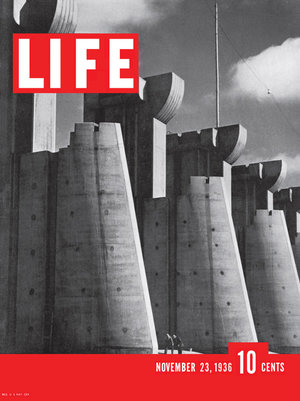

The mammoth size of the entire complex was just as jaw-dropping to me as it had been to the New Dealers and most Americans in the 1930s. That same spillway, for instance, had been the subject of the famous first cover of Life Magazine by Margaret Bourne-White in 1936.

When she visited in 1936 the town of Fort Peck housed thousands but once the job was over, the town quickly diminished and when you take an overview of Fort Peck, the town, today it seems like a mere bump in what is otherwise an overpowering engineering achievement.

Coming from a state that had headquartered another New Deal era transformation of the landscape–the even larger Tennessee Valley Authority project–I understood a good bit of what Fort Peck meant as I started my work for the state historic preservation plan in 1984. A good thing I knew a little because outside of a Montana Historic Highway marker and a tour of the power plant there was little in the way of public interpretation at Fort Peck thirty years ago.

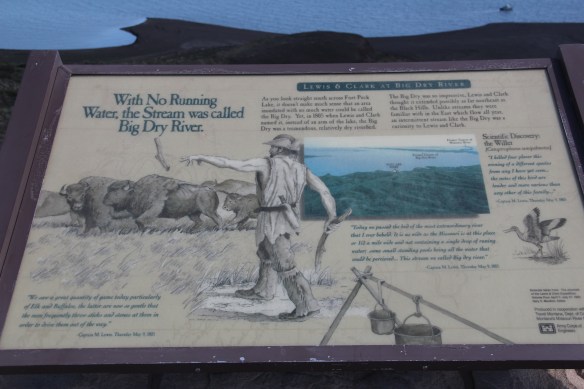

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

First came efforts to better interpret the Corps of Discovery and their travels through this section of the Missouri River 15-20 years ago. The theme was Lewis & Clark in the Missouri River Country, but by the 2010s the region’s demanding weather had taken its toll on the installation.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

At the lake’s edge are additional markers encouraging visitors to imagine the time before the lake when the Big Dry River often meant exactly what it said–the reservoir keeps it full now.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

New interpretive markers combine with a well-defined pull-off to encourage travelers to stop and think about the loss of life that occurred in building the dam. Many of the massive infrastructure projects of the New Deal have similarly sad stories to tell–but few of them do.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

You can explore the landscape with the assistance of the highway markers to a far greater degree than in the past. Even if today it is difficult to “see” the transformation brought about by the massive earthen dam, there are informative markers to help you.

The new visitor center at the Fort Peck powerhouses takes the site’s public interpretation to a new level. Just reading the landscape is difficult; it is challenging to grasp the fact that tens of

workers and families were here in the worst of the Great Depression years and it is impossible to imagine this challenging landscape as once lush with thick vegetation and dinosaurs.

Through fossils, recreations, artwork, historic photographs, recreated buildings, and scores of artifacts, the new interpretive center and museum does its job well. Not only are the complications of the New Deal project spelled out–perhaps a bit too heavy on that score, I mean where else do you see what the “Alphabet Agencies” actually meant–but you get an understanding of worlds lost in the name of 20th century progress.

Is everything covered? Far from it–too much in the new public interpretations focuses on 1800 to 1940, and not how Fort Peck has the harbinger of the Cold War-era Pick-Sloan Missouri Basin reject that totally transformed the river and its historic communities. Nor is there enough exploration into the deep time of the Native Americans and what the transformation of the river and the valley meant and still means to the residents of the Fort Peck Indian Reservation. There’s still work to be done to adequately convey the lasting transformation that came to this section of Montana in the mid-1930s.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

St. Joseph Catholic Church, perched now on a barren bluff facing the lake, was moved about 2.5 miles east to its present location in 1954. Originally near the river in what was then known as the Canton Valley settlement, the church building is one of the state’s oldest, dating to 1874-1875 and is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The proud Gothic styled church is the remnant of one of the valley’s earliest settlements.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

The dam is 422 feet tall and stretches across the river for 3,055 feet–well over a 1/2 mile. It creates a huge reservoir, extending 90 miles to the north and into British Columbia, among the ten largest reservoirs in the nation. And like that, a historic river valley became a recreational lake in a joint project between the United States and Canada.

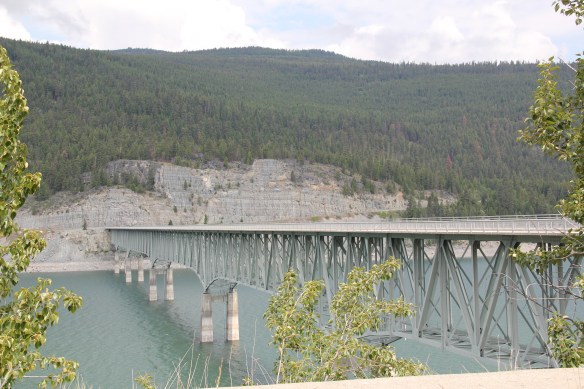

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

The Lake Koocanusa Bridge, which provides access to a Mennonite community and a backroad way to Yaak, is the state’s longest, and in many ways, its most spectacular multi-truss bridge. The bridge is 2,437 feet long, and stands, depending on water level, some 270 feet above the lake.

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once

There was no interpretation at this bridge in 1984, but the scenic highway designation has led to the placement of overlooks and interpretive markers at some places along the lake. One wishes for the same at the Montana town that the lake displaced, Rexford. This once small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

small river town had to move, or be inundated. And since the move took place in the mid to late 1960s, the town embodies the mid-century modern aesthetic, both in the design of many buildings but also in the town plan itself as the federal government finished relocating Rexford in the early 1970s.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.

school by itself is a fascinating statement of both design but also a community’s determination to stay, no matter what the federal government threw their way. Needless to say, in 1984 I paid Rexford no attention–nothing historic was there, it was all new. But now it is clear what a important place in Lincoln County’s 20th century history Rexford came to be.