There’s been a bit of winter in Tennessee in early January 2018 and my university has been closed for two days due to three inches of snow (that’s no misprint). Days like this one lead me to reflection of my jaunt across Big Sky Country in the cold of February to the warmth of mid-May 1984. I had spent 2 months at my cubbyhole in the basement of the Montana Historical Society, shown below, and I was ready I

thought to hit the road. Wonders of all sorts I would find and here are just a few of the special (admittedly perhaps not spectacular to outsiders) places I encountered.

Just up the tracks from the opening image at the southern tip of Beaverhead County was the Hotel Metlen in Dillon. A grad student recently asked me about it, having come across it while trolling the internet. It sounds like a fleabag the student remarked–I probably didn’t help when I recalled staying there for 10 bucks in 1984. But what a great Second Empire-styled railroad hotel!

It had upgraded during my last visit in 2012–still classy in a dumpy way, if that makes any sense.

On the opposite end of the state, at Thompson Falls, was another favorite lodging spot, a classic 1950s motor lodge, the Falls Motel. Spiffy now but still Mom and Pop and so far away from the chain experience of today.

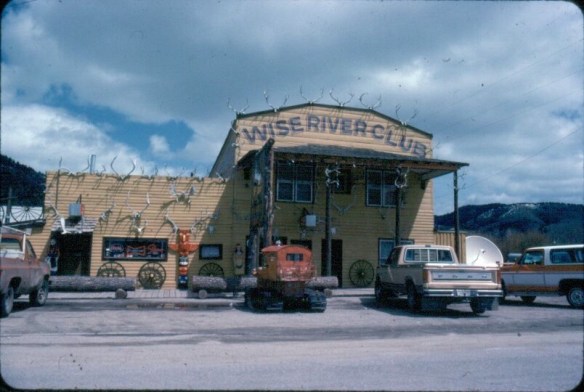

But as regulars of this blog know, I didn’t care where I stayed as long as beef, booze, and pie were nearby. Real rules for the road. The beef could range from the juicy roadside burgers from Polson (the b/w image) to the great huge steaks at Willow Creek (the yellow tinted roadhouse).

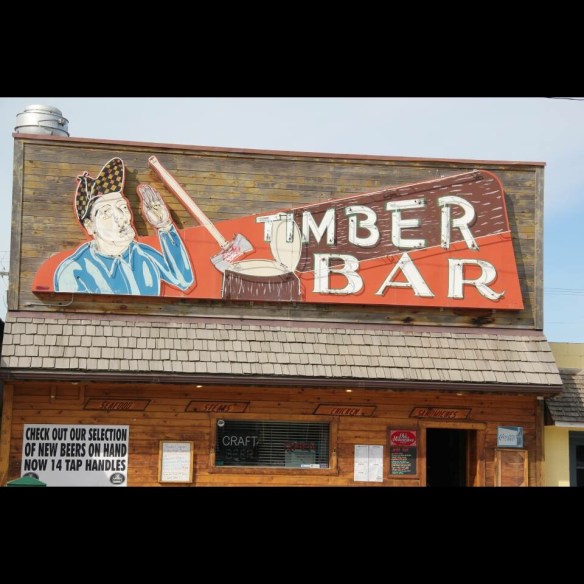

And speaking of roadhouses Wise River Club from 1984 above is still going strong and as friendly as ever. While the owners keep changing at Big Timber–the sign still

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

chops away and the beer is still cold. That is what you need on the road.

Wait! Pie matters too, represented by the Wagon Wheel in Drummond, above. Southerners do brag about pie, and I believed in that regional myth, until I traveled Montana. I swear that there are most great pie places in a single Montana County (say, Cascade) than all of Tennessee. On cold days I still think of a Montana cup of coffee (always strong) and a piece of grit pie. In 1984 I just needed that one afternoon stop to push on for a few more hours of driving and documenting the captivating landscape of the Big Sky Country.

On the outskirts of town, the 1920s monument to David Thompson was the centerpiece of the town’s heritage tourism attractions in 1984-1985, now it is more of an afterthought. David Thompson was a Welsh-Canadian who established the first trading post in this river valley, called Saleesh House, for the tribe with whom this veteran of both the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company had targeted for the fur trade. His last visit to Saleesh House came in the winter of 1812. Thompson, I thought in 1984, was a very important figure in Montana history but increasingly a neglected trader–in fact most of the early traders, like those of the American Fur Company on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, are neglected, even though significant places associated with them remain intact on the state’s landscape.

On the outskirts of town, the 1920s monument to David Thompson was the centerpiece of the town’s heritage tourism attractions in 1984-1985, now it is more of an afterthought. David Thompson was a Welsh-Canadian who established the first trading post in this river valley, called Saleesh House, for the tribe with whom this veteran of both the Hudson Bay Company and North West Company had targeted for the fur trade. His last visit to Saleesh House came in the winter of 1812. Thompson, I thought in 1984, was a very important figure in Montana history but increasingly a neglected trader–in fact most of the early traders, like those of the American Fur Company on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, are neglected, even though significant places associated with them remain intact on the state’s landscape. About one hundred years after David Thompson’s last winter at Saleesh House, an entirely different landscape emerged along the Clark’s Fork River, one that introduced the recent technology of electricity to the region. To support and encourage the development of hydroelectric facilities, the city of Thompson Falls combined with investors to build what became known as the “High Bridge,” a way for automobile traffic to cross this gorge in the Clark’s Fork and unite settlement on both sides of the river.

About one hundred years after David Thompson’s last winter at Saleesh House, an entirely different landscape emerged along the Clark’s Fork River, one that introduced the recent technology of electricity to the region. To support and encourage the development of hydroelectric facilities, the city of Thompson Falls combined with investors to build what became known as the “High Bridge,” a way for automobile traffic to cross this gorge in the Clark’s Fork and unite settlement on both sides of the river. The High Bridge was an early 20th century Montana engineering marvel. It was 588 feet in length, designed for automobile traffic, with a 18-feet wide deck standing on a combination of Pratt and Parker trusses. It is the longest bridge of its kind in Montana.

The High Bridge was an early 20th century Montana engineering marvel. It was 588 feet in length, designed for automobile traffic, with a 18-feet wide deck standing on a combination of Pratt and Parker trusses. It is the longest bridge of its kind in Montana.

But within two years, residents and officials combined together to place the bridges and hydroelectric facilities in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. They were preserved, but still not used, for a generation.

But within two years, residents and officials combined together to place the bridges and hydroelectric facilities in the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district. They were preserved, but still not used, for a generation. In 2009-2010, residents worked with local, state, and federal government officials to restore the bridge, add a pedestrian deck, and to open the bridge and either side of the bridge as a public park. Funding in part came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, one of the ways that short-lived federal building effort benefited historic preservation in Montana small towns.

In 2009-2010, residents worked with local, state, and federal government officials to restore the bridge, add a pedestrian deck, and to open the bridge and either side of the bridge as a public park. Funding in part came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, one of the ways that short-lived federal building effort benefited historic preservation in Montana small towns. The High Bridge experience not only reconnected Thompson Falls to its river roots, it also creates an unique experience for heritage travelers. The site is not that far different from 100 years ago, giving you the chance to cross a river and peer below but also to realize just how “wild” automobile traffic was in the 1910s and 1920s.

The High Bridge experience not only reconnected Thompson Falls to its river roots, it also creates an unique experience for heritage travelers. The site is not that far different from 100 years ago, giving you the chance to cross a river and peer below but also to realize just how “wild” automobile traffic was in the 1910s and 1920s. In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core.

In my state historic preservation plan work of 1984-1985, Thompson Falls became one of my favorite stops. No one much in the professional field had been surveyed here yet, and then I was particularly interested in how the Northern Pacific Railroad transformed the late territorial landscape. As the image above shows, Thompson Falls was a classic symmetrical-plan railroad town, with a mix of one and two-story buildings from the turn of the 20th century. I focused on this commercial core. The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

The public meeting at the mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse was well attended and most were engaged with the discussion: the pride, identity, and passion those in attendance had for their history and their interest in historic preservation was duly noted. The courthouse itself was not a concern–it dated to 1946 and wasn’t even 40 years old then. But now I appreciate it as a good example of Montana’s post-World War II modern movement, designed by Corwin & Company in association with Frederick A. Long

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

Little did I understand, however, that the sparks of a local community effort were already burning–and within two years, in 1986, Thompson Falls had placed many of its key historic properties in the National Register of Historic Places.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The old county jail (1907) has been transformed into a museum, both preserving one of the town’s oldest properties but also creating a valuable heritage tourism attraction. The contractors were Christian and Goblet, a local firm that had a part in the construction of the town’s building boom once it was designated as the county seat.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century.

The mid-20th century Sanders County Courthouse is to the west of the commercial core and it marks how the town stretched to the west in the latter decades of the century. Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks.

Along with the conversion of businesses and the adaptive reuse of older buildings, Thompson Falls also has located key community institutions, such as the local library first established in 1921, along Main Street facing the railroad tracks. But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.

But many community institutions–fraternal lodges such as the Masonic Lodge above, the public schools, and churches are on the opposite side of the tracks along the bluffs facing the commercial core. Thompson Falls is a very good example of how a symmetrical plan could divide a railroad town into distinctive zones.