On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

As soon as you get past the 1966 entrance gates, you find a cemetery that is certainly historic–established as the town was beginning in the 1880s and still used by community over 125 years later. Mountain View is also aesthetically interesting in its overall plan, with its intricate pattern of curvilinear drives and well-ordered arrangement of graves, then several of the grave markers themselves are impressive Victorian statements, of grief, of family, and of pride of accomplishment.

The section set aside for Union veterans of the Civil War was the most interesting historic feature to me. As explored in other posts over the last three years, Montana has many reminders of the Civil War era within its built environment. Clearly in the early decades of the cemetery, this section with its separate flag pole and government-issued grave markers was very similar to what a national cemetery might be. The generation that established the cemetery also wished to remember and signal out for praise the veterans of the great war that had just consumed the nation.

Within this section of Mountain View are also grave markers that are not government issued slabs of marble but that are more expressed of the sense of loss felt by the family. Below is the granite pulpit, with a bible resting on top, for Frank Baker, who died in 1896 but, as the marker notes, was a veteran of Company I of the 49th New York Infantry.

The David K. Buchanan marker, of the stone masonry type associated with the Woodmen of the World in other Yellowstone Valley cemeteries, dates to 1907, and records the calvary career of this Union veteran from Pennsylvania in the “civel war.” (original spelling)

Mountain View has several impressive examples of these Woodmen of the World grave markers that have a floral tree motif, with limbs sawn off to suggest how the body of society was lessened by the individual’s death.

Of particular interest is the marker for the Rickard family where the two trees, one for each spouse and one child , are linked together, symbolizing a family tightly intertwined in death as they were in life.

The George Gannon grave marker is a variation on the Woodmen trees, where a logs carved in stone serve as a base for an open book that tells his story. Victorian era cemeteries are often very expressive, and the Mountain View Cemetery in Livingston has many other

interesting grave markers scattered throughout its grounds. The cemetery, with its beautiful setting, well-kept grounds, and expressive memorials, give night to the historic people of Livingston in a way that streetscapes and historic houses rarely capture.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

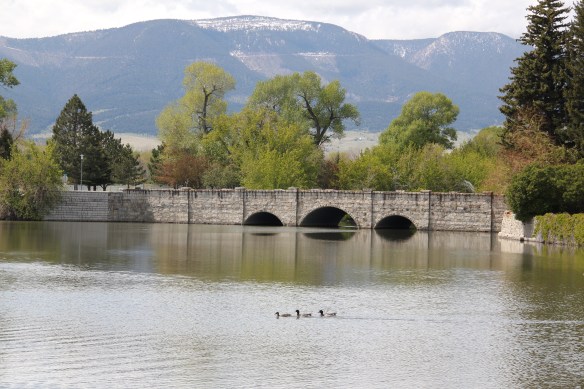

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention. Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community. Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Livingston was one of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s most important division points. Not only did the massive and architecturally ornate passenger station, discussed in the previous blog, serve as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, it contained various company offices, serving as a nerve center for the thousands of miles of railroad line. If you do the typical tourist thing in Livingston, you pay attention to the depot and the many late 19th and early 20th century buildings south of the tracks.

Livingston was one of the Northern Pacific Railroad’s most important division points. Not only did the massive and architecturally ornate passenger station, discussed in the previous blog, serve as a gateway to Yellowstone National Park, it contained various company offices, serving as a nerve center for the thousands of miles of railroad line. If you do the typical tourist thing in Livingston, you pay attention to the depot and the many late 19th and early 20th century buildings south of the tracks. But to find where the real work of the railroad took place, you have to locate the underpass that takes you to the north side of the tracks, and the extensive Northern Pacific railroad shops. This area is not as busy as it once was, but enough buildings remain and enough activity takes place 24-7 that you quickly grasp that here is the heartbeat of the line. In the photo above, one early shop building, the lighter color brick building to the right center, still stands. Most others date to the line’s diesel conversion in the mid-20th century.

But to find where the real work of the railroad took place, you have to locate the underpass that takes you to the north side of the tracks, and the extensive Northern Pacific railroad shops. This area is not as busy as it once was, but enough buildings remain and enough activity takes place 24-7 that you quickly grasp that here is the heartbeat of the line. In the photo above, one early shop building, the lighter color brick building to the right center, still stands. Most others date to the line’s diesel conversion in the mid-20th century. With the mountains to the south, and the outlines of the town visible as well, the shops are impressive statements of corporate power and determination, and how railroads gave an industrial cast to the landscape.

With the mountains to the south, and the outlines of the town visible as well, the shops are impressive statements of corporate power and determination, and how railroads gave an industrial cast to the landscape. The north side, in many ways, was a separate world. Here the homes may date to the Victorian era too, but they are not the stylish period interpretations found in numbers on the south side. Rather they are vernacular styled cottages, or unadorned homes typical of America’s turn-of-the-century working class.

The north side, in many ways, was a separate world. Here the homes may date to the Victorian era too, but they are not the stylish period interpretations found in numbers on the south side. Rather they are vernacular styled cottages, or unadorned homes typical of America’s turn-of-the-century working class.

The school was converted into a community museum some 30 years ago, and if you visit the grand passenger station, you also need to stop at the school, to get a fuller picture of Livingston, the railroad town.

The school was converted into a community museum some 30 years ago, and if you visit the grand passenger station, you also need to stop at the school, to get a fuller picture of Livingston, the railroad town.

The above block of commercial businesses was once better known as the Montana Hotel while the block below, called the Hiatt Hotel in more recent years, was the Park Hotel, opened in 1904 to take advantage of increased tourist business due to the new Northern Pacific depot. Noted Montana architect C.S. Haire was the designer.

The above block of commercial businesses was once better known as the Montana Hotel while the block below, called the Hiatt Hotel in more recent years, was the Park Hotel, opened in 1904 to take advantage of increased tourist business due to the new Northern Pacific depot. Noted Montana architect C.S. Haire was the designer. These buildings served tourists in the summer months but throughout the years they relied on the “drummer” trade. Drummers were a word used to describe traveling businessmen, who rode the rails constantly, stopping at towns large and small, to drum up business for their companies. They too, like the machine shop workers on the south side, were a constant presence on the railroad lines of 100 years ago, and helped to make the lines hum with their travel and their stories.

These buildings served tourists in the summer months but throughout the years they relied on the “drummer” trade. Drummers were a word used to describe traveling businessmen, who rode the rails constantly, stopping at towns large and small, to drum up business for their companies. They too, like the machine shop workers on the south side, were a constant presence on the railroad lines of 100 years ago, and helped to make the lines hum with their travel and their stories.

Continuing west you soon encounter post-World War II service stations and motels, some updated, some much like they were, on the outskirts of town and then, boom, you are in the heart of Livingston, facing the commanding presence of the Northern Pacific depot complex with warehouses–some now converted to new uses–coming first and then

Continuing west you soon encounter post-World War II service stations and motels, some updated, some much like they were, on the outskirts of town and then, boom, you are in the heart of Livingston, facing the commanding presence of the Northern Pacific depot complex with warehouses–some now converted to new uses–coming first and then massive passenger station itself. Opened in 1902, the passenger station was an architectural marvel for the new state, designed by Reed and Stem, who would continue on to great fame as the architects of Grand Central Station in New York City. The station, interestingly, is not Classical Revival in style–certainly the choice of most architects for their grand gateways along the nation’s rail line–but a more restrained interpretation of Renaissance Revival style, completed in red brick.

massive passenger station itself. Opened in 1902, the passenger station was an architectural marvel for the new state, designed by Reed and Stem, who would continue on to great fame as the architects of Grand Central Station in New York City. The station, interestingly, is not Classical Revival in style–certainly the choice of most architects for their grand gateways along the nation’s rail line–but a more restrained interpretation of Renaissance Revival style, completed in red brick. The building is not particularly inviting for locals coming from the business district to the depot–that was not its primary audience. Rather the grand entrance is track side, where passengers headed to Yellowstone National Park could depart for food, fun, frivolity, whatever they needed before the journey into the wildness of Yellowstone.

The building is not particularly inviting for locals coming from the business district to the depot–that was not its primary audience. Rather the grand entrance is track side, where passengers headed to Yellowstone National Park could depart for food, fun, frivolity, whatever they needed before the journey into the wildness of Yellowstone.

Travelers were welcome to use the grand covered walkways to enter the depot proper, or to take a side visit to the railroad’s cafe, Martin’s as I

Travelers were welcome to use the grand covered walkways to enter the depot proper, or to take a side visit to the railroad’s cafe, Martin’s as I knew it back in the day, a place that rarely slept and always had good pie. The cafe changed its orientation from the railroad to the road as automobile travelers on U.S. 10 began to dominate the tourist market. Now it has been restored as a local brew pub.

knew it back in the day, a place that rarely slept and always had good pie. The cafe changed its orientation from the railroad to the road as automobile travelers on U.S. 10 began to dominate the tourist market. Now it has been restored as a local brew pub.

Directly facing the center of the passenger station was the mammoth Murray Hotel–a flea bag operation in the 1980s but now recently restored as a hipster place to be, especially its signature bar.

Directly facing the center of the passenger station was the mammoth Murray Hotel–a flea bag operation in the 1980s but now recently restored as a hipster place to be, especially its signature bar.

Imagine my pleasant surprise last year when I found that Gil’s still existed but now had been converted into a decidedly up-scale establishment, far removed from the 1980s.

Imagine my pleasant surprise last year when I found that Gil’s still existed but now had been converted into a decidedly up-scale establishment, far removed from the 1980s. I don’t know if I have encountered a more fundamentally changed place–cheap trinkets gone, let the wood-fired pizzas come on.

I don’t know if I have encountered a more fundamentally changed place–cheap trinkets gone, let the wood-fired pizzas come on. I was not so blinded in 1984 by the concept of the “metropolitan corridor” that I ignored the distinctive Victorian storefronts of Livingston–how could I since they all, in a way, fed into the tracks. But when I got to the end of that distinctive business district and watched the town, in my

I was not so blinded in 1984 by the concept of the “metropolitan corridor” that I ignored the distinctive Victorian storefronts of Livingston–how could I since they all, in a way, fed into the tracks. But when I got to the end of that distinctive business district and watched the town, in my mind, fade into the Rockies, I had captured the obvious but had missed the bigger picture–that’s the next story.

mind, fade into the Rockies, I had captured the obvious but had missed the bigger picture–that’s the next story.