Highland Cemetery, established in 1911, is a private, perpetual care cemetery that serves as the primary burial ground in the city. Located south of the city, the cemetery’s many trees and irrigated grounds make the place a shady park-like oasis in an otherwise barren prairie.

Paris Gibson (d. 1920), the civic capitalist who founded and nurtured the city, is buried not far from the gates. Like with most ventures in Great Falls, Gibson had encouraged the creation of a new, privately administered cemetery adjacent to the original Highland Cemetery (now known as Old Highland Cemetery).

His grave marker, a tall chiseled stone, is different than most. Low rectangular, regularly sized and spaced markers characterize the cemetery in almost every direction you look.

As is the case with many Montana cemeteries from over 100 years ago, you will find sponsored sections for fraternal organizations, such as the monument identifying members of the Elk Lodge, see below, as well as members of the Masons and Woodmen of the World.

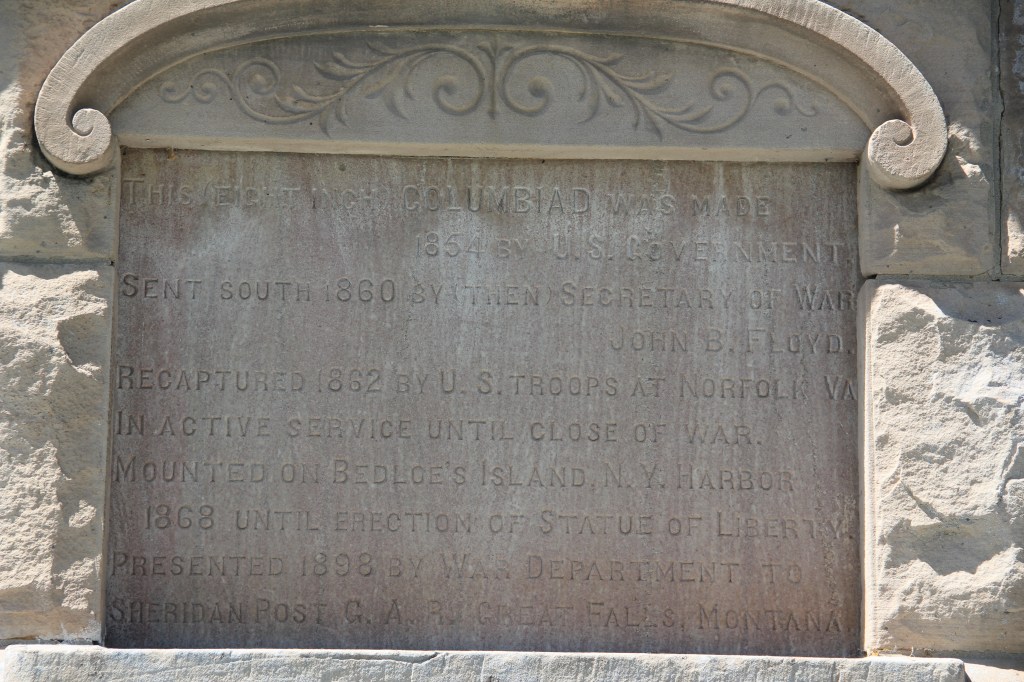

The cemetery’s opening coincided with the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the American Civil War. A centerpiece of the cemetery is a large, expansive veterans section, centered on a mounted Columbiad cannon, given by New York City to the Sheridan camp of the Grand Army of the Republic in Great Falls. U.S. soldiers, and some Confederate soldiers, are buried in a circle facing the cannon and the flag. The massive stone base for the cannon tells its story and adds on a side panel “In Memory of the Boys Who Wore Blue, 1861-1865.” It is the most compelling Civil War monument in a Montana cemetery.

Famous individuals besides Paris Gibson have been buried at Highland Cemetery. Governor Edwin Norris (d. 1924) is represented by a tall obelisk marker.

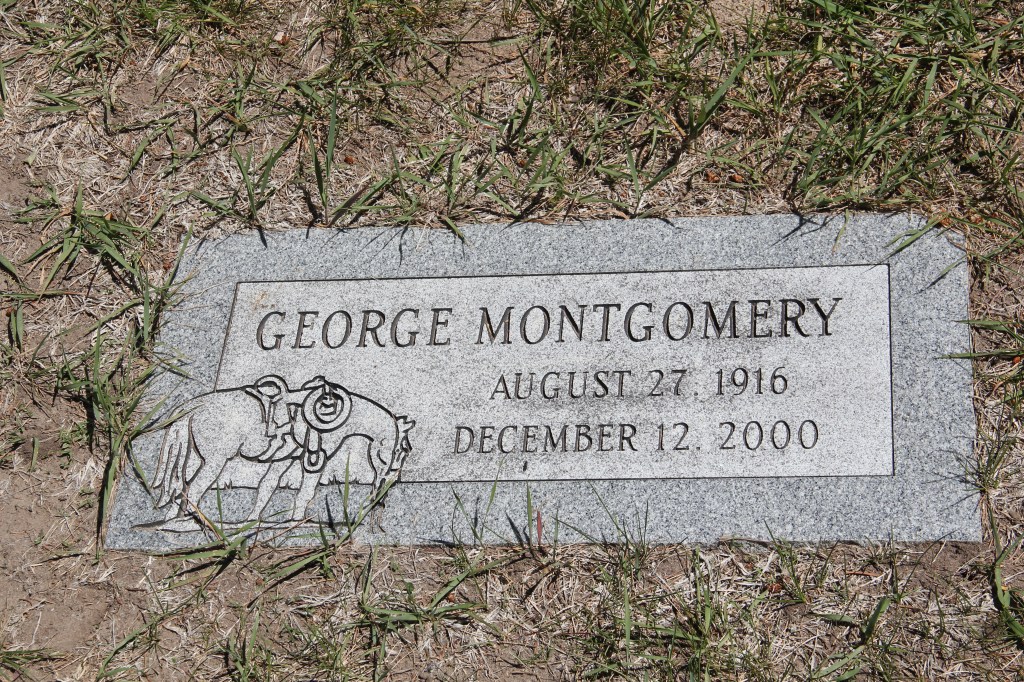

Television and movie actor George Montgomery (d. 2000), who was once married to actress and singer Dinah Shore, is also buried here, represented by a full sized metal statue, dressed in cowboy gear. It might seen odd, at first glance, for a Hollywood star to be buried at Highland, but Montgomery was born in the small town of Brady in Pondera County. By being interred at Highland, Montgomery in a sense had come home.

The most famous Montanan to be buried here is Charles M. Russell, who, like Gibson is represented by a chiseled stone boulder, with his trademark initials in a metal plaque affixed to the stone. Nearby is the grave for his wife, and manager, Nancy Russell. A scholar of Russell’s art and life, Frederic Renner (d. 1987), is also buried nearby. Speak of devotion to your subject!

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment.

Kalispell’s Main Street–the stem of the T-plan that dates to the town’s very beginning as a stop on the Great Northern Railway–has a different mix of businesses today than 30 years ago when I visited during my state historic preservation plan survey. It also now is a historic district within National Register of Historic Places, noted for its mix of one-story and two-story Western Commercial style businesses along with large historic hotels and an opera house for entertainment. The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Opera House, and I’m sorry you have to love the horse and buggy sign added to the front some years ago, dates to 1896 as the dream of merchant John MacIntosh to give the fledging community everything it needed. On the first floor was his store, which over the years sold all sorts of items, from thimbles to Studebakers. The second floor was a community space, for meetings, a gymnasium, and even from a brief period from 1905 to 1906 a skating rink. In this way, MacIntosh followed the ten-year-old model of a much larger building in a much larger city, the famous Auditorium Building in Chicago, providing Kalispell with a major indoor recreation space and landmark. Allegedly over 1000 people attended a performance of Uncle Tom’s Cabin soon after the opening.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

The Alpine Lighting Center dates to 1929 when local architect Fred Brinkman designed the store for Montgomery Ward, the famous Chicago-based catalog merchant. Its eye-catching facade distinguished it from many of the other more unadorned two-part commercial blocks on Main Street.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood.

project, and the Art Moderne landmark Intermountain bus station–once so proudly featured in the Clint Eastwood and Jeff Bridges movie, “Thunderbolt and Lightfoot,” part of that decade from the mid-1970s to mid-1980s when Montana was suddenly in the lens of Hollywood. All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the

All of these buildings and places help to give Great Falls its unique sense of self, and its sense of achievement and promise. And that is not to even mention the fun, funky stuff, such as the Polar Bears and having the supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the

supper club experience of 50 years ago at Borrie’s in Black Eagle. Stepping back into time, or looking into a future where heritage stands next to the atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience.

atomic age, Great Falls and its environs–from Fort Benton to the northeast to Fort Shaw to the southwest–can give you that memorable heritage area experience.