On this wintery day I return to Big Hole National Battlefield, one of the most solemn and sacred places in Big Sky Country, out of a request from a MTSU graduate student who is trying to come to grips with western battlefields and their interpretation. In 2013 I posted about the new visitor center museum exhibits at Big Hole, lauding them for taking the “whole story” approach that we have always attempted to take with our work in Tennessee through the Tennessee Civil War National Heritage Area.

The Big Hole Battlefield exhibits, how at least 5 years old, do the whole story approach well, as you can see from the panel above where voices from the past and present give you the “straight talk” of the Nez Perce perspective.

One of the most telling quotes on how the military viewed the original residents of the northern Rockies is not that of Sherman–damning enough–but the one above by General O.O. Howard, best known in the American South for his determination and leadership of the Freedman’s Bureau and its attempt to secure civil rights for the newly emancipated enslaved of the nation.

The exhibit panels, together with a new set of exterior interpretive panels scattered across the battlefield, do an excellent job of allowing visitors to explore, reflect, and decide for themselves. The more comprehensive approach to telling the story is nothing really new. NPS historian Robert Utley called for it decades ago, and Marc Blackburn recently reviewed efforts across the country in his excellent book, Interpreting American Military History (2016). For the Big Hole itself, all scholars can benefit from Helen A. Keremedjiev’s ethnographic study of this park and other military sites in Montana in his now decade old master’s thesis at the University of Montana.

Of course Big Hole Battlefield is now part of a larger thematic effort, the Nez Perce Historical Park, to mark and tell the story of Chief Joseph and his attempt to find a safe haven in land that once the tribe had dominated. These few images, which, as many of you regular readers know, can be enlarged and viewed intently, only start the exploration–you really have to go to the Big Hole to understand what the events of 1877 meant to the new residents flooding the country and those who had lived and thrived there for centuries.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it.

The town’s grain elevators really are its landmark–the town is along the railroad spur and sits off Montana Highway 16–without the elevators you might not even notice it. Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south.

Agriculture defines the use of the largest buildings of the town, and while it is a tiny place Reserve serves a much larger region of ranches located between Plentywood, the county seat, to the north and Medicine Lake, to the south. This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning.

This larger audience for services in Reserve helps to explain the survival of the Reserve Post Office–so many tiny Montana towns have lost the one federal institution that had been there since the town’s beginning. But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

But naturally I will urge you to make a stop, however brief, at the Reserve Bar. This concrete block building, with its period glass block windows, is a friendly place, and a great way to talk with both residents and surrounding farmers.

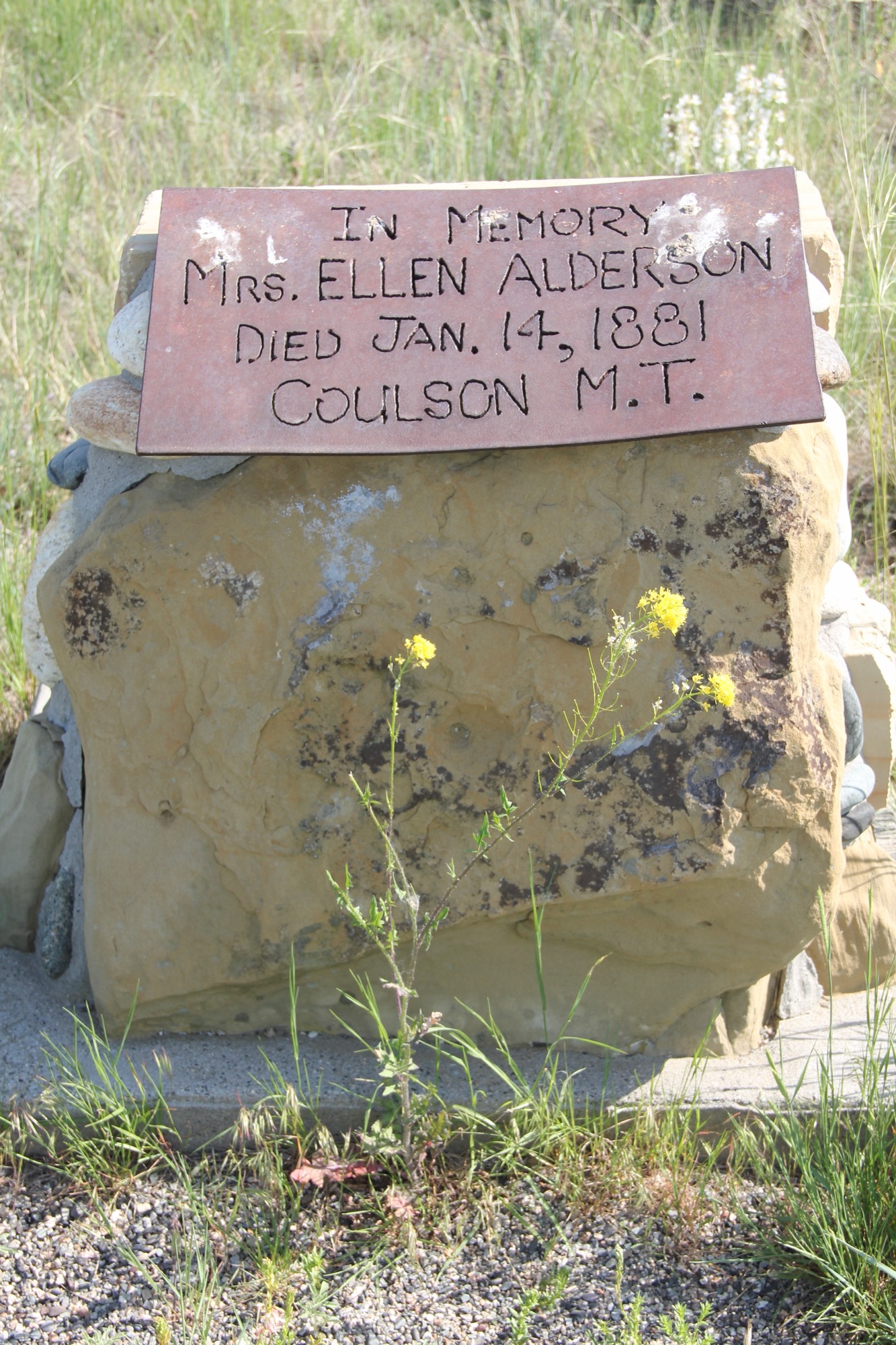

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

On the northwestern outskirts of Livingston is Mountain View Cemetery, another of the historic properties that certainly existed when I carried out the 1984-1985 fieldwork for the Montana state historic preservation plan, but since it was a cemetery, we as a field gave it, or any cemetery for that matter, little consideration thirty years ago.

This brief overview does not do justice to the city’s historic cemeteries. Certainly I gave Boothill consideration in the 1984-1985 and even wrote about it in both of my books on Billings history. But Mountview is a historic landscape that only now I recognize–and I hope to do more exploration in the future.

This brief overview does not do justice to the city’s historic cemeteries. Certainly I gave Boothill consideration in the 1984-1985 and even wrote about it in both of my books on Billings history. But Mountview is a historic landscape that only now I recognize–and I hope to do more exploration in the future.