Dillon is not a large county seat but here you find public buildings from the first third of the 20th century that document the town’s past aspirations to grow into a large, prosperous western city. It is a pattern found in several Montana towns–impressive public buildings designed to prove to outsiders, and perhaps mostly to themselves, that a new town out in the wilds of Montana could evolve into a prosperous, settled place like those county seats of government back east.

Dillon is not a large county seat but here you find public buildings from the first third of the 20th century that document the town’s past aspirations to grow into a large, prosperous western city. It is a pattern found in several Montana towns–impressive public buildings designed to prove to outsiders, and perhaps mostly to themselves, that a new town out in the wilds of Montana could evolve into a prosperous, settled place like those county seats of government back east.

The public library dates to 1901-1902, constructed with funds provided by the Carnegie Library building program of steel magnate Andew Carnegie. This late example of Richardsonian Romanesque architecture came from architect Charles S. Haire, who would become one of the state’s most significant early 20th century designers.

The library reflected the town’s taste for the Romanesque, first expressed in the grand arched entrance of the Beaverhead County Courthouse (1889-1890), designed by architect Sidney Smith. The central clock tower was an instant landmark for the fledging railroad town in 1890–it remains that way today.

The Dillon City Hall also belongs to those turn-of-the-20th century public landmarks but it is a bit more of a blending of Victorian and Classical styling for a multi-purpose building that was city hall, police headquarters, and the fire station all rolled into one.

The Dillon City Hall also belongs to those turn-of-the-20th century public landmarks but it is a bit more of a blending of Victorian and Classical styling for a multi-purpose building that was city hall, police headquarters, and the fire station all rolled into one.

The most imposing Classical Revival public structure in Dillon is also the smallest: the public water fountain, located between the railroad depot and the Dingley Block.

A New Deal era post office introduced a restrained version of Colonial Revival style to Dillon’s downtown. The central entrance gave no hint to the marvel inside, one of the

A New Deal era post office introduced a restrained version of Colonial Revival style to Dillon’s downtown. The central entrance gave no hint to the marvel inside, one of the

state’s six post office murals, commissioned and executed between 1937 and 1942. The Dillon work is titled “News from the States” painted by Elizabeth Lochrie in 1938. It is a rarity among the murals executed across the country in those years because it directly addressed the mail and communication in early Beaverhead County. Ironically, few of the post office murals actually took the mail as a central theme.

state’s six post office murals, commissioned and executed between 1937 and 1942. The Dillon work is titled “News from the States” painted by Elizabeth Lochrie in 1938. It is a rarity among the murals executed across the country in those years because it directly addressed the mail and communication in early Beaverhead County. Ironically, few of the post office murals actually took the mail as a central theme.

The New Deal also introduced a public modernism to Dillon through the Art Deco styling of the Beaverhead County High School, a building still in use today as the county high school.

The New Deal also introduced a public modernism to Dillon through the Art Deco styling of the Beaverhead County High School, a building still in use today as the county high school.

A generation later, modernism again was the theme for the Dillon Middle School and Elementary school–with the low one-story profile suggestive of the contemporary style then the rage for both public and commercial buildings in the 1950s-60s, into the 1970s.

A generation later, modernism again was the theme for the Dillon Middle School and Elementary school–with the low one-story profile suggestive of the contemporary style then the rage for both public and commercial buildings in the 1950s-60s, into the 1970s.

The contemporary style also made its mark on other public buildings, from the mid-century county office building to the much more recent neo-Rustic style of the Beaverhead National Forest headquarters.

The contemporary style also made its mark on other public buildings, from the mid-century county office building to the much more recent neo-Rustic style of the Beaverhead National Forest headquarters.

The Beaverhead County Fairgrounds is the largest public landscape in Dillon, a sprawling complex of exhibition buildings, grandstand, and rodeo arena located on the outskirts of town along the railroad line.

But throughout town there are other reminders of identity, culture, and history. Dillon is energized through its public sculpture, be it the cowboys in front of the Chamber of Commerce office or the Veterans Memorial Park on the northern outskirts.

This birds-eye view of the town is at the Beaverhead County Museum at the railroad depot. It shows the symmetrical plan well, with two-story commercial blocks facing the tracks and depot, which was then just a frame building. To the opposite side of the tracks with more laborer cottages and one outstanding landmark, the Second Empire-style Hotel Metlen. The Metlen, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, remains today, one

This birds-eye view of the town is at the Beaverhead County Museum at the railroad depot. It shows the symmetrical plan well, with two-story commercial blocks facing the tracks and depot, which was then just a frame building. To the opposite side of the tracks with more laborer cottages and one outstanding landmark, the Second Empire-style Hotel Metlen. The Metlen, listed in the National Register of Historic Places, remains today, one of the state’s best examples of a railroad hotel. I recognized the building as such in the 1984 state historic preservation plan and my book, A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, included the image below of the hotel.

of the state’s best examples of a railroad hotel. I recognized the building as such in the 1984 state historic preservation plan and my book, A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History, included the image below of the hotel. This three-story hotel served not only tourists but especially traveling businessmen–called drummers because they were out “drumming up” business for their companies. The interior has received some restoration work in the last 30 years but little has changed in the facade, as they two images, one from 1990 and the other from 2012, indicate.

This three-story hotel served not only tourists but especially traveling businessmen–called drummers because they were out “drumming up” business for their companies. The interior has received some restoration work in the last 30 years but little has changed in the facade, as they two images, one from 1990 and the other from 2012, indicate.

built environment has many stories to tell.

built environment has many stories to tell. Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as

Jackson, Montana, is another favorite place of mine in Beaverhead County. Located on Montana Highway 278, far away from any neighborhoods, the town dates to the 1880s, as this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

this area of the Big Hole Valley opened up to ranching. Its name came from Anton Jackson, the first postmaster; the town still has a historic post office building even though its

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984.

Jackson grows significantly during the winter, as it is an increasingly popular winter get-away destination, centered on the historic Jackson Hot Springs, which had been upgraded and significantly expanded since my last visit in 1984. But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats!

But my real reason to tout the wonders of Jackson, Montana, lie with a simple but rather unique adaptive reuse project. A turn of the 20th century church building has been converted into a hat manufacturer business, the Buffalo Gal Hat Shop–and I like hats! Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Grant is another ranching town along a Montana secondary highway, this time Montana Highway 324. Like Jackson, it too has enough year-round residents and children from nearby ranches to support a school, a tiny modernist style building while an older early 20th century school building has become a community center.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers.

Back when I visited in 1984, Monte Elliott (only the third owner of the property he claimed) showed off his recent improvements made within the context of a business location that dated to the Civil War era. The lodge still keeps records from those early days that they share with interested visitors. In the 21st century, new owner Jason Vose additionally upgraded the facilities, but kept the business’s pride in its past as he further expanded its offerings to hunters and travelers. Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Far to the north along Montana Highway 43 is the Big Horn River Canyon, a spectacular but little known landscape within the state. Certainly anglers and hunters visited here, but the two towns along the river in this northern end of Beaverhead County are tiny places, best known perhaps for their bars as any thing else.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

Just as important as a town anchor is the Wise River Community Center, which began in the gable-front frame building as the Wise River Woman’s Club but has expanded over the last 30 years into the larger building you find today.

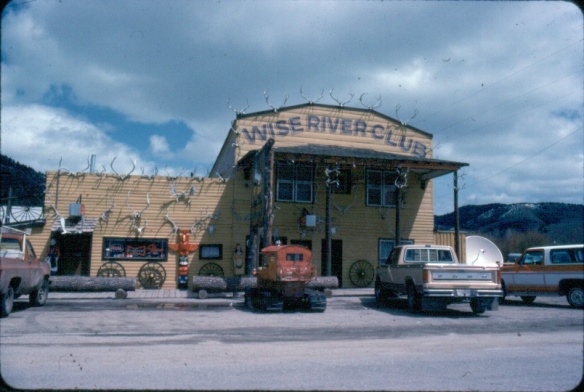

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building.

The liveliness of that 1984 exterior–note the mini-totem pole, the log benches, wagon wheels, and yes the many antlers defining the front wall–is muted in today’s building. But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar.

But the place is still there, serving locals and travelers, and a good number of the antlers now grace the main room of the bar. Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions.

Wise River, unlike Dewey but similar to Jackson, has been able to keep its historic general store in business. The post office moved out in the 1990s to the new separate building but the flag pole remains outside to mark how this building also served both private and public functions. The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

The country towns of Beaverhead County help to landmark the agricultural history of this place, and how such a huge county as this one could still nurture tiny urban oases. Next I will leave the rural landscape and look at Beayerhead’s one true urban landscape–the county seat of Dillon.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

Let’s start this theme with the railroad/ federal highway towns. Monida, at the state border with Idaho, is a good place to start, first established as a place on the Utah and Northern Railroad line as it moved north toward the mines at Butte in 1881. Monica had a second life as a highway stop on the old U.S. Highway 91 that paralleled the tracks, as evident in the old garages left behind.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

which possesses a Montana welcome center and rest stop. That’s important because at this stop you also can find one of the state’s mid-20th century examples of a tourist welcome center, which has been moved to this stop and then interpreted as part of the state’s evolving roadside architecture.

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early

The reclamation project, which stored water for irrigation, also covered the site of Camp Fortunate, a very important place within the larger narrative of the Lewis and Clark Expedition and its relationships and negotiations with the Shoshone Indians. An early