There are few places in the nation more important than the broad river valley at the confluence of the Judith and Missouri rivers in central Montana, a place only accessible by historic gravel roads. When I first visited in 1984, I came from the Fergus County side through Winifred.

Why is Judith Landing so important? It was a vital and frequently used crossroads for Northern Plains tribes for centuries. Then in 1805 as Lewis and Clark traveled on the Missouri, they camped at the confluence (private property today). In 1844, The American Fur Company established Fort Chardon, a short-lived trading post.

In 1846 Indigenous leaders of several tribes met at Council Island to discuss relations between the Blackfeet and other northwest tribes. In 1855 leaders from the Blackfeet, Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Nez Perce returned to Council Island to negotiate the Lame Bull treaty, which established communal hunting areas and paved the way for white settlement in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

Settlement first came with trading posts, serving a nearby army base, Camp Cooke (1866-1870) and connecting steamboat traffic on the Missouri to nearly mining camps (like Maiden). When the U.S. government moved the base, Fort Benton merchant T.C. Power developed his own businesses and post at Judith Landing and established “Fort Clagett” to the immediate west. In the 1880s he partnered with Gilman Norris to create the famous PN Ranch from the remnants of these early settlement efforts.

Visiting this place was a major goal of the 1984 historic preservation plan survey. At that time the ranch was still operating as a ranch and the one slide that I took shows several of the historic and new ranch buildings, yes from a distance because in the work I always respected private property boundaries.

Over the next 40 years I worked in Montana many times but never made a return to Judith Landing. I knew that the historic buildings of the PN ranch were there and that a National Register district existed affording some protection. Then in late 2024 came the news that Montana State Parks was acquiring 109 acres of the historic property and would create the Judith Landing State Park. I couldn’t wait to return and visited in late September 2025.

At that time there had been little in the way of “park development.” I hope it largely stays that way because the sense of time and place conveyed by the rustic, rugged surroundings is overwhelming. You can be lost in history.

The half-dovetail “mail barn” was moved to its location on the ranch about 1890. It continued to serve as a post office until 1919.

The stone warehouse was severely damaged in a flood 50 years ago—but it is hanging on, and indicates how important trade and commodities were here 150 years ago. It operated as a store until 1934 and then became a barn for the next 40 years until the flood of 1975.

Gilman and Pauline Norris’s own ranch house, a turn of the twentieth century Shingle-style beauty, speaks to the ranch’s success. perhaps it can be restored as a future park interpretive center, open in the summer.

The important point is that, now, finally, Judith Landing is a state park, conserving one of the most remarkable places of the northern plains.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks.

Since I last visited in 2012 efforts have been underway to secure additional acres and to preserve a buffer around the property since growth and highway expansion between Missoula and Stevensville has engulfed Lolo. The park now has 51 acres and represents quite an achievement by the non-profit Travelers Rest Preservation and Heritage Association, local government, and Montana State Parks. Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

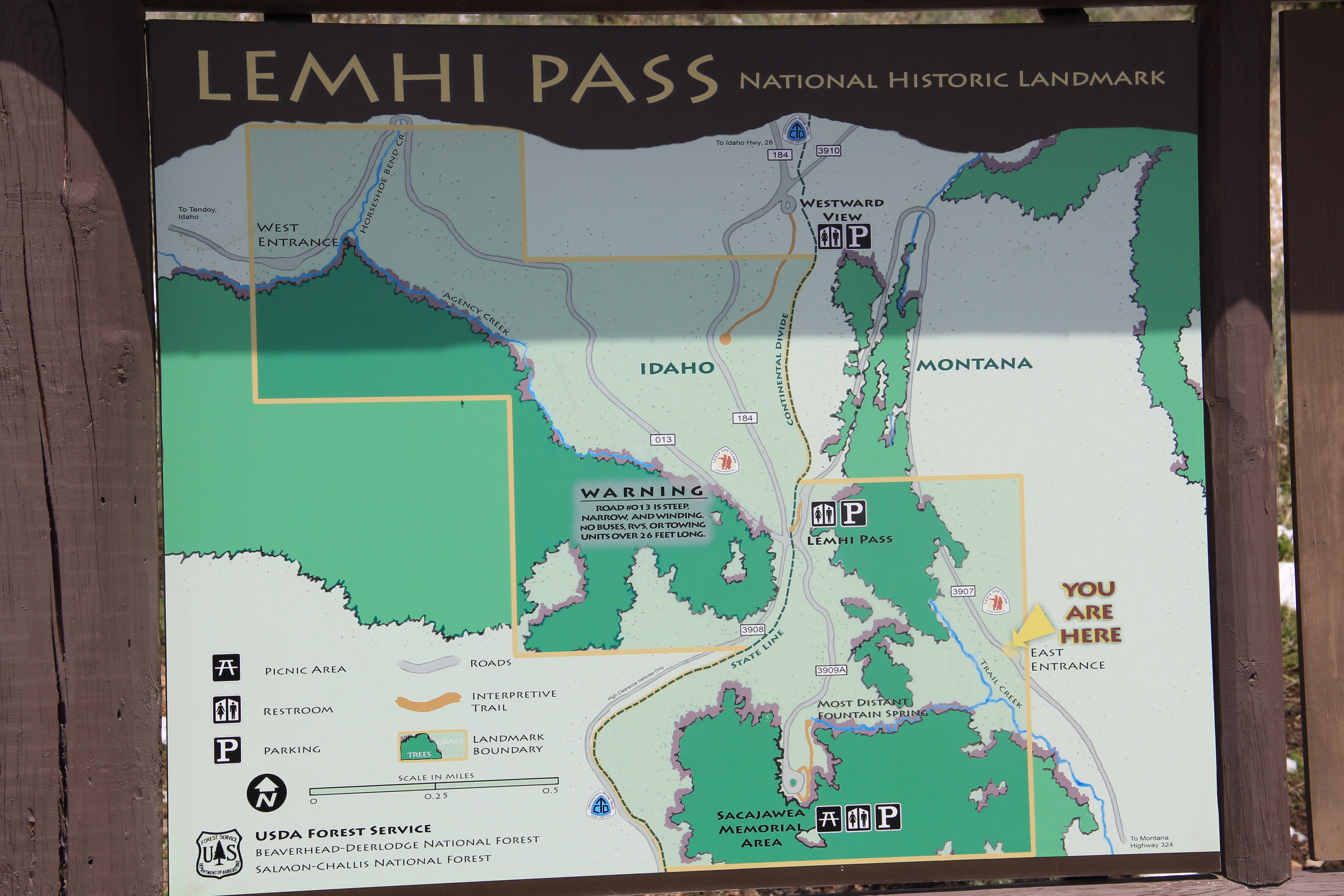

Beaverhead County’s history has deep roots, perhaps never deeper than at the high mountain passes that divide it from neighboring Idaho. We have already taken a look at Monida Pass, but now let’s shift to the western border and consider Lemhi Pass (Lemhi Road is the image above) and Bannock Pass, both at well over 7000 feet in elevation.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

Lemhi Pass is a magnificent place, reached by a wide dirt road that climbs up to 7300 feet. The roadbed is modern, and lies over a path worn by centuries of Native Americans who traveled this path between mountain valleys in present-day Montana and Idaho. That deep past is why the more famous Lewis and Clark Expedition took this route over the Bitterroot–and the Corps of Discovery connection is why the pass has been protected in the 20th century. The pass is also connected with Sacajawea, since her tribe, the Shoshone, often used it to cross the mountains.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area.

This kiosk by the U.S. Forest Service is part of the new public interpretation of the property, both at the start of the pass to the top of the mountain itself at the Sacajawea Memorial Area. Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

Bannock Pass, comparatively has received little in public interpretation. Unlike Lemhi, it is not a National Historic Landmark associated with Lewis and Clark. For today’s travelers, however, it is a much more frequently used way to cross the Rockies despite its 300 foot higher elevation. A historic site directional sign leads to one interpretive

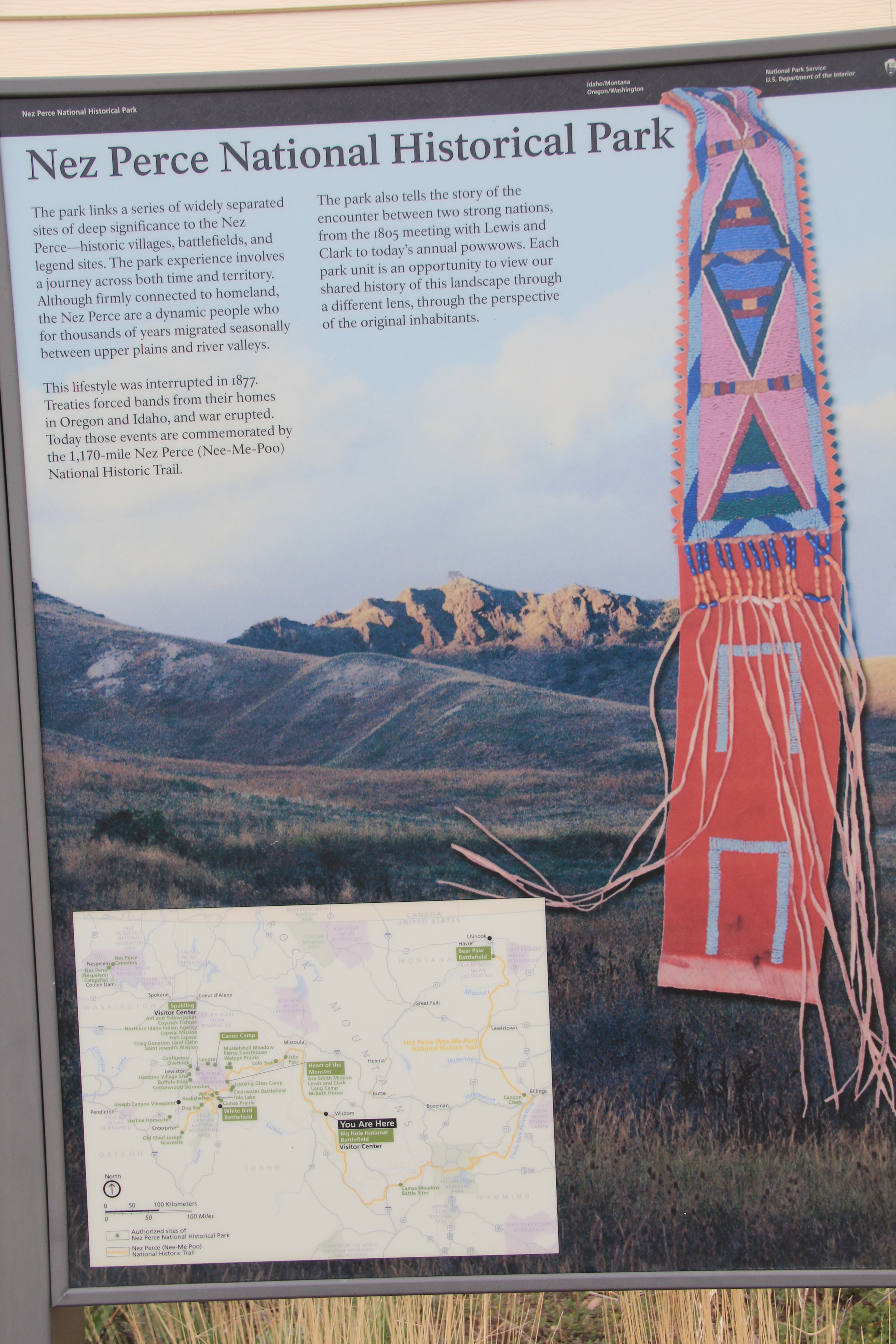

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

It was a snowy Memorial Day when I crossed Lost Trail and Chief Joseph passes on my way to Big Hole Battlefield. Once again I was impressed by the recent efforts of the U.S. Forest Service to interpret the epic yet tragic journey of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce in 1877, especially the Trail Creek Road that parallels Montana Highway 43.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.

Canada was underway. Today the Nez Perce National Historic Trail and Park mark that journey into history. The park today is frankly an amazing transformation, from a preserved battlefield in the early 1980s that only hinted at the true facts of history to a modern of battlefield interpretation, one that does justice to history and to the Nez Perce story. One only wishes that more western battlefields received similar treatment.