Dominated by the monumental Cruse family mausoleum, Resurrection Cemetery has been a Montana Avenue landmark for over 100 years. It is not the first Catholic cemetery in Helena–the original one was nearer the yards of the Northern Pacific Railroad and was closed c. 1906-1908, when Resurrection Cemetery was under development. The first cemetery became abandoned and many markers and crypts were not removed until the late 1940s and 1950s. Then in the 1970s, the city finished the process and turned the cemetery into Robinson Park, where a small interpretive marker still tells the story of the first Catholic cemetery.

Resurrection is a beautifully planned cemetery, with separate sections, and standardized markers, for priests and for the sisters, as shown above. Their understated tablet stones mark their service to God and add few embellishments. Not so for the merchant and political elite buried in the historic half of Resurrection Cemetery. “Statement” grave markers abound, such as the Greek Revival temple-styled mausoleum for the Larsen family, shown below.

An elaborate cross marks the family plot of Martin Maginnis, an influential and significant merchant and politician from the early decades of the state’s history (but who is largely forgotten today). Nearby is the family plot for one of Maginnis’ allies in central Montana and later in Helena, T. C. Power.

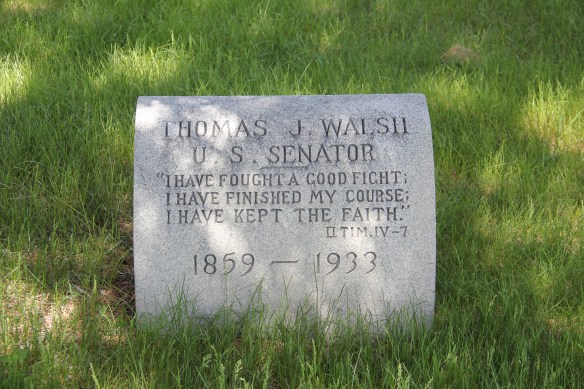

Joseph K. Toole, a two-time Governor of Montana, is also buried with a large but not ornate stone marker, shown below. Former senator Thomas Walsh is nearby but what is

most interesting about the Walsh family plot is the striking Arts and Crafts design for his

daughter Elinor Walsh, who died as a young woman. I have not yet encountered a marker similar to hers in all of Montana.

Another compelling marker with statuary is that of another young woman rendered in marble, a memorial to James and Catherine Ryan.

Another compelling marker with statuary is that of another young woman rendered in marble, a memorial to James and Catherine Ryan.

Thomas Cruse, who struck it rich with the Drumlummon mine at Marysville, had no qualms about proclaiming his significance and the grandest cemetery memorial in Montana bears his name. Cruse already had put up at least one-third of the funding for the magnificent High Gothic-styled St. Helena Cathedral in downtown Helena. At Resurrection, Cruse (who died in late 1914) was laid to rest in a majestic classical-style family mausoleum where his wife and his daughter were also interred (both proceeded Cruse in death). The Cruse mausoleum is the centerpiece of Resurrection’s design.

But the monuments for the rich and famous at Resurrection are the exceptions, not the rule. In the historic half of the cemetery, most markers are rectangular tablet types. The cemetery also has a separate veterans section.

But my visit on Memorial Day 2018 left me with the feeling that the cemetery is an under-appreciated historic property. There are no signs of true neglect, but it was so quiet on Memorial Day that I did think the place had become an almost forgotten historic asset–an afterthought in today’s busy world. I hope not–because this cemetery has many jewels to explore and appreciate. Perhaps the most striking–certainly most rare to see–are the cast iron baskets–or bassinets, see below, that surround two children’s graves.

But my visit on Memorial Day 2018 left me with the feeling that the cemetery is an under-appreciated historic property. There are no signs of true neglect, but it was so quiet on Memorial Day that I did think the place had become an almost forgotten historic asset–an afterthought in today’s busy world. I hope not–because this cemetery has many jewels to explore and appreciate. Perhaps the most striking–certainly most rare to see–are the cast iron baskets–or bassinets, see below, that surround two children’s graves.

plots–certainly the ironwork was a status symbol in the late 19th century and there is no one statement. Families adorned their graves with fences much as they surrounded their houses in the nearby neighborhoods.

plots–certainly the ironwork was a status symbol in the late 19th century and there is no one statement. Families adorned their graves with fences much as they surrounded their houses in the nearby neighborhoods.

Benton Avenue Cemetery is worth a new consideration for its many different forms, materials, and designs. When I lived in Helena some thirty-five years ago, I gave it scant attention–it deserves so much more.

Benton Avenue Cemetery is worth a new consideration for its many different forms, materials, and designs. When I lived in Helena some thirty-five years ago, I gave it scant attention–it deserves so much more.

Then in October 2017, someone set a fire that almost totally destroyed the school building. When I pulled into Big Timber the following May, I expected to see a parking lot or at least an empty lot (the local Episcopal Church had purchased the property). The damaged building was still there, however, giving me one final chance to take an image, one that now represents dreams dashed, and yet another historic building gone from the Montana landscape.

Then in October 2017, someone set a fire that almost totally destroyed the school building. When I pulled into Big Timber the following May, I expected to see a parking lot or at least an empty lot (the local Episcopal Church had purchased the property). The damaged building was still there, however, giving me one final chance to take an image, one that now represents dreams dashed, and yet another historic building gone from the Montana landscape.

The date of most markers are from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. Mostly made of granite and sandstone, with some marble as well, the grave markers reflect Victorian styles and Classical influences. Herman Gans’ marker from 1901, seen below, is a mixture of both.

The date of most markers are from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. Mostly made of granite and sandstone, with some marble as well, the grave markers reflect Victorian styles and Classical influences. Herman Gans’ marker from 1901, seen below, is a mixture of both.

The looming presence of the school grounds is a worry for future preservation of the cemetery–could it be possibly overlooked, ignored, and abandoned? One online resource about the cemetery remarks that there are more Jews buried in the cemetery than live in Helena today. But this sacred place is a powerful reminder of the contributions of the Jewish community to Helena’s growth and permanence. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the cemetery should be valued as one of the city’s oldest and most significant historic properties.

The looming presence of the school grounds is a worry for future preservation of the cemetery–could it be possibly overlooked, ignored, and abandoned? One online resource about the cemetery remarks that there are more Jews buried in the cemetery than live in Helena today. But this sacred place is a powerful reminder of the contributions of the Jewish community to Helena’s growth and permanence. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the cemetery should be valued as one of the city’s oldest and most significant historic properties.