Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Along Interstate I-90 as you travel northwest into Idaho, St. Regis is the last town of any size in Montana, and, at that it only counts just over 300 residents. The town has a long significant history in transportation. Old U.S. Highway 10 follows part of the historic Mullan Road–the Mullan monument above marks that route in St. Regis. The town lies at the confluence of the Clark’s Fork River and the St. Regis River. It is also the point where

Since my last visit in 1984, school officials had expanded the St. Regis school and added a new entrance but the historic facade still commands attention.

the Milwaukee Road left the Clark’s Fork corridor that it had followed from southwest Montana–the Northern Pacific kept on that route however–while and tackled a much more demanding path through the Rockies–that of the St. Regis River towards Taft.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

As the photos above show, one of the Milwaukee’s bridges over the Northern Pacific right-of-way has been cut while the interstate rises high above and dwarfs both earlier railroads along the Clark’s Fork River. From St. Regis to Taft, the Milwaukee Road route has new life. In the 21st century the U.S. Forest Service and local residents have worked diligently to preserve the corridor, not to restore the tracks but to find a new recreational use for the abandoned railroad bed.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

Note in the photograph above, how one of the distinctive electric power poles that carried electricity to the Milwaukee’s engines remains in place. In the central part of Montana, many of these poles are long gone from the corridor. The Milwaukee’s stretch of electrified track began in Harlowton and ended in Idaho–and the St. Regis to Idaho section has some of most intact features of this distinctive engineered landscape.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The village of Haugan is also the location of the Savenac Nursery, which the U.S. Forest Service established here c. 1907, as the Milwaukee’s tracks were being constructed. Under the direction of Elers Koch of the forest service, Savenac’s became one of the largest seedling operations in the department of agriculture, yielding as many of 12 million seedlings in one year.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The historic nursery is open to the public, another example of the important work that the Forest Service has carried out for both preservation and public interpretation in the last 30 years. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the property has a museum that operates in the tourist season.

The nursery is also among the most important landscapes in the state associated with the Civilian Conservation Corps, which built most of the extant historic buildings in the 1930s.

Thus it is most appropriate that a monument to the CCC workers has been located on land between the interstate highway and the nursery grounds.The monument, dedicated in 2005, notes that agency’s work in Montana from 1933 to 1942, a decade of transformation in the state’s public landscape that millions have experienced since then.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Haugan is also home to one of the state’s modern pieces of roadside architecture along the interstate, Silver’s truck stop, restaurant, bar, and casino.

Saltese lacks the formal monuments found at its neighbor, but this small Milwaukee Road town has an industrial landmark in the high iron trestle that cuts through its residential side. There you can see one of the rectangular wooden catenary supports for the electric lines to the speeding trains. The route itself is part of recreational trail that takes bikers and hikers to the National Register-listed tunnel and railroad yards ending at the St. Pass Pass Tunnel (1908) at Taft near the Idaho border.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

Saltese’s contemporary styled school from c. 1960 remains but has closed. Its historic motels and businesses, as well as an abandoned c. 1930 gas station on old U.S. Highway 10, welcome travelers from the west to Montana.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

The railroad trail route from Taft provides access to some of most spectacular industrial ruins of the old Milwaukee route left in the west.

of the Milwaukee Road in 1980, the town has steadily lost population-2oo less residents in 2015 compared to my first visit 30 years earlier. Never a large place–the town’s top population was 1242 residents in 1960–Superior has several landmark buildings from its railroad days but only one has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

of the Milwaukee Road in 1980, the town has steadily lost population-2oo less residents in 2015 compared to my first visit 30 years earlier. Never a large place–the town’s top population was 1242 residents in 1960–Superior has several landmark buildings from its railroad days but only one has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places. That one place, the Superior School, is spectacular and its tall central tower has long served as a community beacon. Built 1915-16 by contractor Charles Augustine, the high school reflected Colonial Revival style, and later community growth led to wing additions in 1925, shown above, and in 1947.

That one place, the Superior School, is spectacular and its tall central tower has long served as a community beacon. Built 1915-16 by contractor Charles Augustine, the high school reflected Colonial Revival style, and later community growth led to wing additions in 1925, shown above, and in 1947. Another Colonial Revival-styled public building is the Mineral County Courthouse, 1920, complete with its colonial-inspired cupola. Mineral County was created in 1914. This building is more complete rural interpretation of Colonial Revival style than the school.

Another Colonial Revival-styled public building is the Mineral County Courthouse, 1920, complete with its colonial-inspired cupola. Mineral County was created in 1914. This building is more complete rural interpretation of Colonial Revival style than the school.

The historic Strand Theater (c. 1915) operated in 1984 but closed in 2013 and remained shuttered when I visited in 2015, no doubt a victim of not only the home theatre phenomenon but also the switch to digital delivery of movies in this decade. This theatre, however, is a rare and important building from the homesteading era of the 1910s.

The historic Strand Theater (c. 1915) operated in 1984 but closed in 2013 and remained shuttered when I visited in 2015, no doubt a victim of not only the home theatre phenomenon but also the switch to digital delivery of movies in this decade. This theatre, however, is a rare and important building from the homesteading era of the 1910s. From the same decade, the historic Masonic Mountain Lodge still operates, serving as another community outlet and center in Superior. The town’s population height in the 1960s led to the construction of the institutional Ranch-style of the Superior High School, one of two bits of mid-century modernism in Superior.

From the same decade, the historic Masonic Mountain Lodge still operates, serving as another community outlet and center in Superior. The town’s population height in the 1960s led to the construction of the institutional Ranch-style of the Superior High School, one of two bits of mid-century modernism in Superior.

The other example dates to 1958 and represents yet another example of modern design in a rural Catholic Church in Montana. St Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Church is also a

The other example dates to 1958 and represents yet another example of modern design in a rural Catholic Church in Montana. St Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Church is also a Ranch-styled inspired design, although its stand-alone but visually and physically linked low bell tower is unique compared to other Montana Catholic churches from this era.

Ranch-styled inspired design, although its stand-alone but visually and physically linked low bell tower is unique compared to other Montana Catholic churches from this era. The church is Superior’s best contribution to Montana modernism and complements well the Victorian influence found at the town’s historic United Methodist Church, built almost 50 years earlier. Note that both churches have low bell towers.

The church is Superior’s best contribution to Montana modernism and complements well the Victorian influence found at the town’s historic United Methodist Church, built almost 50 years earlier. Note that both churches have low bell towers.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

The two railroads and the river that shaped Missoula also carved the landscape to the northwest. Following the Clark’s Fork River to the northwest, the Milwaukee Road passes through Mineral County, adding to a transportation corridor that, earlier, included the Mullan Road, and then later U.S. Highway 10. It is now the route of Interstate Highway I-90 as i heads west to Idaho and then Washington State.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road.

As the interstate crosses the Clark’s Fork River near Tarkio it bypasses the earlier transportation network. A particular marvel is the Scenic Bridge, listed in the National Register in 2010, especially how the bridge of U.S. 10, built in 1928, was designed in dialogue with the earlier high-steel bridge of the Milwaukee Road. The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

The Scenic Bridge has been closed to traffic but is safe to walk across, creating great views of both bridges and the Clark’s Fork River–travel here has always been challenging.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

Twenty years historic preservationists stepped up to add numerous properties to the National Register throughout the county. In addition to the passenger depot, the Montana Valley Book Store, above, was listed. This two-story false front building, with attached one-story building, was once the town’s commercial heart and known as Bestwick’s Market–it has been close to the heart of book lovers for years now. Montana Valley Book Store was a relatively new business when I first visited in 1984 but now it is one of the region’s cultural institutions, especially when a visit is combined with a quick stop at the adjacent Trax Bar.

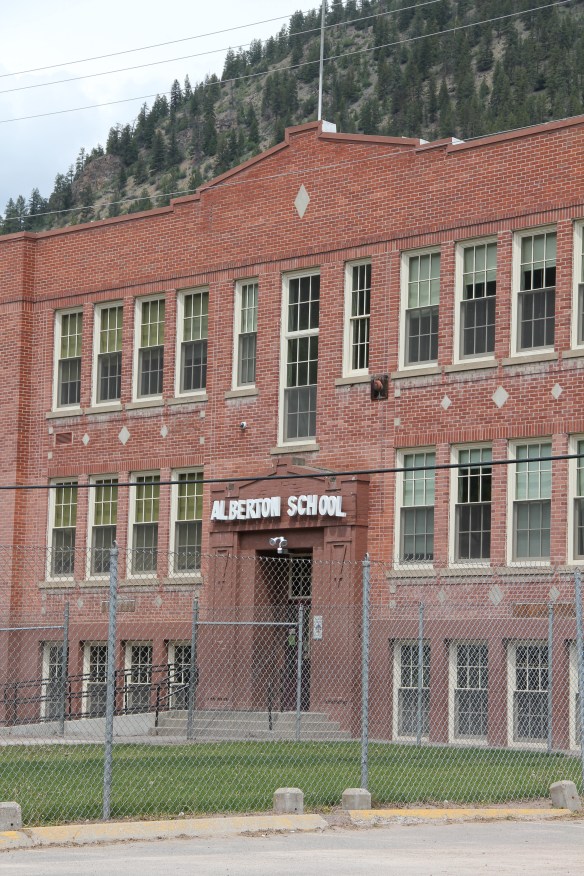

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work.

The historic three-story brick Alberton High School (now the Alberton School) operated from 1919 to 1960 as the only high school facility within miles of the railroad corridor. It too is listed in the National Register and was one of the community landmarks I noted in the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism.

I gave no notice to the replacement school, the modern Alberton High School, c. 1960. That was a mistake–this building too reflects school design ideas of its time–the Space Age of the late 1950s and 1960s, when open classrooms, circular designs, and a space-age aesthetic were all the rage. Alberton High School is one of my favorite small-town examples of Montana modernism. The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.

The school is a modern marvel just as the high school football field and track are reminders of how central the schools are to rural community and identity in Montana. Alberton has held its own in population in the decades since the closing of the Milwaukee Road, largely due to its proximity to Missoula and the dramatic gorges created by the Clark’s Fork River. Change is probably coming, and hopefully these landmarks will remain in service for years to come.