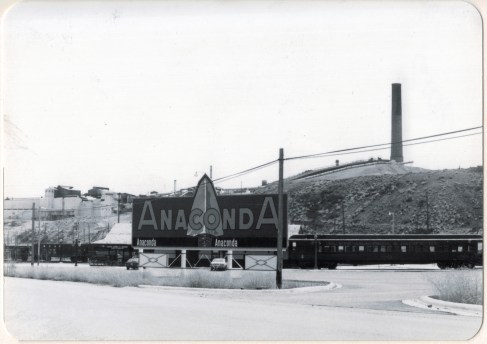

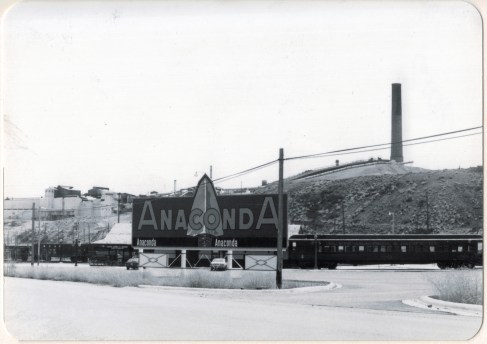

As a 20th century industrial landscape, Anaconda has few peers in Montana, or even the west. I want to share that landscape in a series of posts that highlight both the well-known and the not so well known properties of the town.

Even as a neophyte to Montana’s history, I understood the significance of the news that the smelter was closing in Anaconda in the early 1980s. I had already taken images of the town’s most defining landmark–the Washoe Stack–and I soon went to Anaconda to take more because no doubt the end of the company meant major change–and many of my friends thought it meant the end of the town itself.

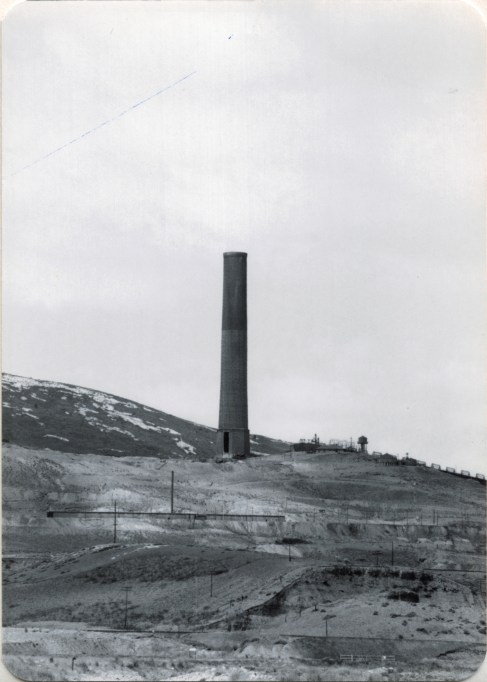

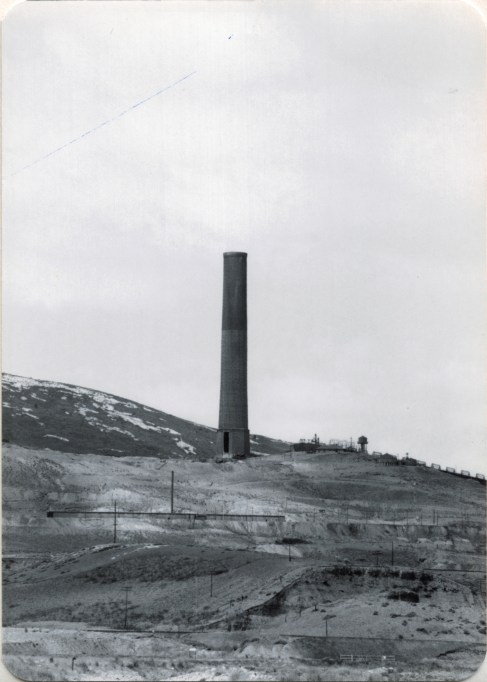

The stack dominates the Deer Lodge Valley moreso than any man-made structure in the state. As I much later wrote for Drumlummon Views in 2009: the Washoe Stack was “built by the Alphonis Chimney Construction Company for the Anaconda Copper Mining Company in 1918. The stack is 585 feet high, 60 feet wide at the top with an interior diameter of 75 feet. Few industrial structures anywhere compare to it. The stack loomed over the company, its workers, its region, and its state as the Anaconda company owned and ran Montana as ‘a commonwealth where one corporation ruled supreme.'” Historian Laurie Mercier interviewed many Anaconda residents in the 1980s. One of her most compelling sessions came with Bob Vine. He believed that the Company and God were all the same in Anaconda: “’Everybody would get up in the morning and they look and see if there was smoke coming out of that stack and if there was, God was in his heaven and all was right with the world, and we knew we were going to have a paycheck.’”

But once the corporation closed its doors and began to scrap the smelter and its works, the stack quickly became an isolated symbol of past times. Again, in the Drumlummon Views essay of 2009 I recalled the efforts to preserve the stack: “A community-wide effort to save the stack was launched because, in the poetic words of local union activist Tom Dickson:

ARCO save that stack, touch not a single brick

Signify the livelihood that made Anaconda tick.

Still let it stand there stark against the sky,

Like a somewhat obscene gesture catching every eye.'”

When I last visited the stack in 2012, Dickson’s wish was true. The stack stands “stark against the sky,” no matter the vantage point.

View from highway 589

From the old stack walking trail and golf course

From the 4-lane highway between the town and interstate

And, perhaps most appropriately, from the town’s cemetery where so many of those who toiled there are buried. The stack is a landmark of engineering achievement–yes–but it is also a landmark that reminds us of corporate impact and community persistence, and it is that later idea: of how Anaconda remains and what it says today that I hope to explore in future posts.