Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

Livingston’s town plan from 1882 was all about the railroad, with the adjacent Yellowstone River an afterthought, at best an impediment since it defined the south end of town. So far from the tracks to be of little worth to anyone, few paid it any attention. 100 years later when I am considering the town for the state historic preservation, I too was all about the railroad and the metropolitan corridor of which it was part. I paid no attention to the river. The town’s schools were on this end, but they were “modern” so did not capture my attention.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

Consequently I missed a bit part of the town’s story, the effort to reform the landscape and create public space during the New Deal era. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) transformed this part of town from 1935 to 1938 expanding an earlier public park into today’s Sacajawea Park.

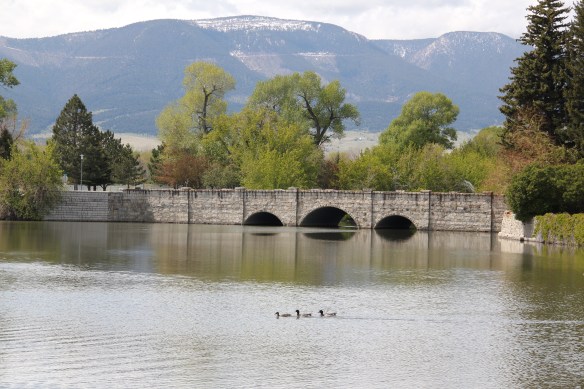

The agency built a diversion dam on the river to create the lagoon for Sacajawea Lake, and added a lovely rustic-styled stone bridge. Later improvements came in 1981.

As in many other communities across the nation, the agency also added a modern outdoor swimming pool, and bathhouse. Plus it built a public amphitheater–several of these still exist in Montana.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

The major addition, however, was the large combination Civic Center and National Guard Armory, an Art Deco-styled building that cost an estimated $100,000 in 1938. It too survives and is in active use by the community.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Tourists now come to this area more often than in the past due to additions made during the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial in the early 21st century. The park is part of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Local sources funded the additional of an interpretive memorial and statue in honor of the July 1806 stop at this place by Sacajawea and her baby Pomp. Mary Michael is the sculptor. The result is a reinvigorated

public space, not only due to the history markers about Lewis, Clark, Sacajawea, and Pomp, but also the obvious community pride in this connection between town, river, and mountains.

Traveling south of Clyde Park on U.S. 89, you pass by the turn-off for Horse Thief Trail, where a historic steel bridge still allows for one-lane traffic over the Shields River; this bridge and snippet of road is part of the original route of U.S 89. That means you are nearing the confluence of the Yellowstone and Shields rivers, and where U.S. Highway 89 crosses the Yellowstone River and takes you into the heart of Park County. Paralleling the modern concrete bridge is a c. 1897 steel Pratt through truss bridge, to serve the Northern Pacific Railroad spur that runs north to Clyde Park then Wilsall. The Northern Pacific called this the Third Crossing of the Yellowstone bridge; the Phoenix Bridge Company constructed it.

Traveling south of Clyde Park on U.S. 89, you pass by the turn-off for Horse Thief Trail, where a historic steel bridge still allows for one-lane traffic over the Shields River; this bridge and snippet of road is part of the original route of U.S 89. That means you are nearing the confluence of the Yellowstone and Shields rivers, and where U.S. Highway 89 crosses the Yellowstone River and takes you into the heart of Park County. Paralleling the modern concrete bridge is a c. 1897 steel Pratt through truss bridge, to serve the Northern Pacific Railroad spur that runs north to Clyde Park then Wilsall. The Northern Pacific called this the Third Crossing of the Yellowstone bridge; the Phoenix Bridge Company constructed it. Before jogging slightly to the west to head to Livingston, the county seat, two places east of the Shields River confluence are worth a look. First is the site of Fort Parker, established as the first Crow Agency in 1869 or the first federal facility in the valley. It operated from this location until 1875.

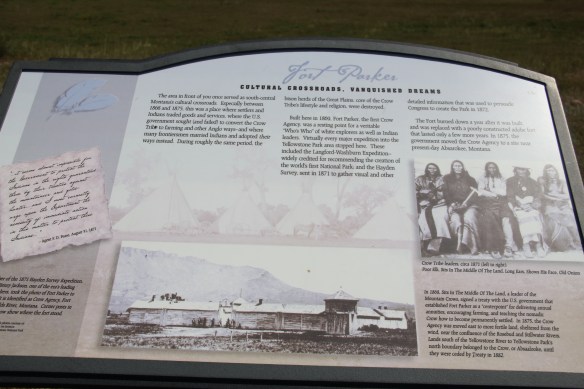

Before jogging slightly to the west to head to Livingston, the county seat, two places east of the Shields River confluence are worth a look. First is the site of Fort Parker, established as the first Crow Agency in 1869 or the first federal facility in the valley. It operated from this location until 1875.

Gladly all of that changed in the 21st century. As a result of another innovative state partnership with land owners, there is an interpretive center for the Fort Parker story, easily accessible from the interstate, which also does not intrude into the potentially rich archaeological remains of the fort. The story told by the historical markers is accurate and comprehensive, from the agency’s beginnings to the land today.

Gladly all of that changed in the 21st century. As a result of another innovative state partnership with land owners, there is an interpretive center for the Fort Parker story, easily accessible from the interstate, which also does not intrude into the potentially rich archaeological remains of the fort. The story told by the historical markers is accurate and comprehensive, from the agency’s beginnings to the land today.

Few remnants of that early white settlement remain today; you can find some just north of Springdale, at Park County’s eastern border, on the north side of the Yellowstone River. Hunter’s Hot Springs was the first attraction, established by Andrew Jackson Hunter in the 1870s, and receiving its last update in the early years of automobile tourism in the 1920s, as shown below in this postcard from my collection. Today, as the Google image below also shows, there are just scattered stones and fences from what had been a showplace for the valley.

Few remnants of that early white settlement remain today; you can find some just north of Springdale, at Park County’s eastern border, on the north side of the Yellowstone River. Hunter’s Hot Springs was the first attraction, established by Andrew Jackson Hunter in the 1870s, and receiving its last update in the early years of automobile tourism in the 1920s, as shown below in this postcard from my collection. Today, as the Google image below also shows, there are just scattered stones and fences from what had been a showplace for the valley.

Commercial businesses once lined the town side of the Northern Pacific tracks. Nothing is open today although trains rumbled down this historic main line every day. What does survive is impressive and worthy of

Commercial businesses once lined the town side of the Northern Pacific tracks. Nothing is open today although trains rumbled down this historic main line every day. What does survive is impressive and worthy of