There are few places in the nation more important than the broad river valley at the confluence of the Judith and Missouri rivers in central Montana, a place only accessible by historic gravel roads. When I first visited in 1984, I came from the Fergus County side through Winifred.

Why is Judith Landing so important? It was a vital and frequently used crossroads for Northern Plains tribes for centuries. Then in 1805 as Lewis and Clark traveled on the Missouri, they camped at the confluence (private property today). In 1844, The American Fur Company established Fort Chardon, a short-lived trading post.

In 1846 Indigenous leaders of several tribes met at Council Island to discuss relations between the Blackfeet and other northwest tribes. In 1855 leaders from the Blackfeet, Salish, Pend d’Oreille, and Nez Perce returned to Council Island to negotiate the Lame Bull treaty, which established communal hunting areas and paved the way for white settlement in the late 1860s and early 1870s.

Settlement first came with trading posts, serving a nearby army base, Camp Cooke (1866-1870) and connecting steamboat traffic on the Missouri to nearly mining camps (like Maiden). When the U.S. government moved the base, Fort Benton merchant T.C. Power developed his own businesses and post at Judith Landing and established “Fort Clagett” to the immediate west. In the 1880s he partnered with Gilman Norris to create the famous PN Ranch from the remnants of these early settlement efforts.

Visiting this place was a major goal of the 1984 historic preservation plan survey. At that time the ranch was still operating as a ranch and the one slide that I took shows several of the historic and new ranch buildings, yes from a distance because in the work I always respected private property boundaries.

Over the next 40 years I worked in Montana many times but never made a return to Judith Landing. I knew that the historic buildings of the PN ranch were there and that a National Register district existed affording some protection. Then in late 2024 came the news that Montana State Parks was acquiring 109 acres of the historic property and would create the Judith Landing State Park. I couldn’t wait to return and visited in late September 2025.

At that time there had been little in the way of “park development.” I hope it largely stays that way because the sense of time and place conveyed by the rustic, rugged surroundings is overwhelming. You can be lost in history.

The half-dovetail “mail barn” was moved to its location on the ranch about 1890. It continued to serve as a post office until 1919.

The stone warehouse was severely damaged in a flood 50 years ago—but it is hanging on, and indicates how important trade and commodities were here 150 years ago. It operated as a store until 1934 and then became a barn for the next 40 years until the flood of 1975.

Gilman and Pauline Norris’s own ranch house, a turn of the twentieth century Shingle-style beauty, speaks to the ranch’s success. perhaps it can be restored as a future park interpretive center, open in the summer.

The important point is that, now, finally, Judith Landing is a state park, conserving one of the most remarkable places of the northern plains.

I used a slide taken in 1982 in all of my public presentations about the Montana state historic preservation plan back in 1984-1985. I found out that few Montanans knew of the place and its history. What has changed since the 1980s? The park is still little known and receives infrequent visitors. In my 2015 fieldwork, I saw signs of new heritage development–the park sign, a bit of improvement to the outdoor interpretive center, and new interpretive exhibits with a more inclusive public interpretation and strong Native American focus.

I used a slide taken in 1982 in all of my public presentations about the Montana state historic preservation plan back in 1984-1985. I found out that few Montanans knew of the place and its history. What has changed since the 1980s? The park is still little known and receives infrequent visitors. In my 2015 fieldwork, I saw signs of new heritage development–the park sign, a bit of improvement to the outdoor interpretive center, and new interpretive exhibits with a more inclusive public interpretation and strong Native American focus.

Successful heritage areas have chronological depth to their history, and places that are of national, if not international, significance. To begin that part of the story, let’s shift to the other side of Cascade County from Belt and explore the landscape and significance of the First Nations Buffalo Jump State Park. When I visited the site in 1984 there was not much to it but the landscape: no interpretive center existed and there were only a few markers. To give the state its due, it then only owned a portion of the site, with the first land acquisition dating to the New Deal. Listed in the National Register in 1974, the site only had opened as a state park a few years earlier, and no one seemed to know much about it or even how to get to it. But as this photograph from “A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History” shows, wow, what a view: it was totally impressive, and had a big story obviously to convey.

Successful heritage areas have chronological depth to their history, and places that are of national, if not international, significance. To begin that part of the story, let’s shift to the other side of Cascade County from Belt and explore the landscape and significance of the First Nations Buffalo Jump State Park. When I visited the site in 1984 there was not much to it but the landscape: no interpretive center existed and there were only a few markers. To give the state its due, it then only owned a portion of the site, with the first land acquisition dating to the New Deal. Listed in the National Register in 1974, the site only had opened as a state park a few years earlier, and no one seemed to know much about it or even how to get to it. But as this photograph from “A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History” shows, wow, what a view: it was totally impressive, and had a big story obviously to convey. Buffalo jumps were ways that the first nations in Montana could effectively kill large number of bisons–by planning, gathering and then stampeding a herd over a steep cliff. Native Americans used this site for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The cliff is hundreds of yards long and kill sites are throughout the property.

Buffalo jumps were ways that the first nations in Montana could effectively kill large number of bisons–by planning, gathering and then stampeding a herd over a steep cliff. Native Americans used this site for hundreds, if not thousands of years. The cliff is hundreds of yards long and kill sites are throughout the property.

State park officials, working with local residents and ranchers, have significantly enhanced the public interpretation at the park since the late 1990s. Hundreds of additional acres have been acquired, better access roads have been installed. and new interpretive features, such as these reproduction sweat lodges on the top of the cliff, have been added to the landscape to physically enhance the Native American feel to the park.

State park officials, working with local residents and ranchers, have significantly enhanced the public interpretation at the park since the late 1990s. Hundreds of additional acres have been acquired, better access roads have been installed. and new interpretive features, such as these reproduction sweat lodges on the top of the cliff, have been added to the landscape to physically enhance the Native American feel to the park. The interpretive center is a model of 21st century Native American-focus history. It provides facilities and exhibits for visitors, and encourages a longer stay and exploration of the site.

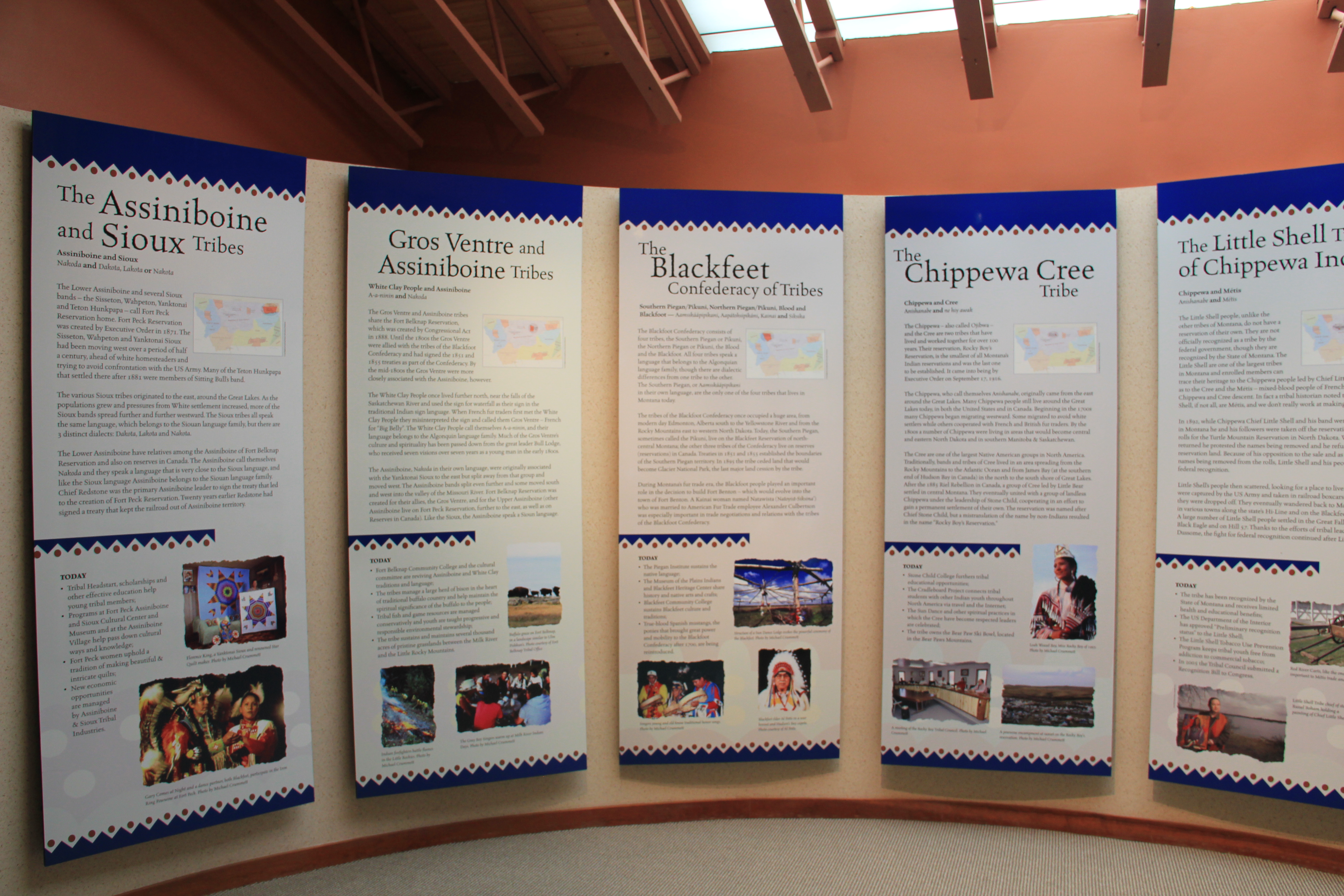

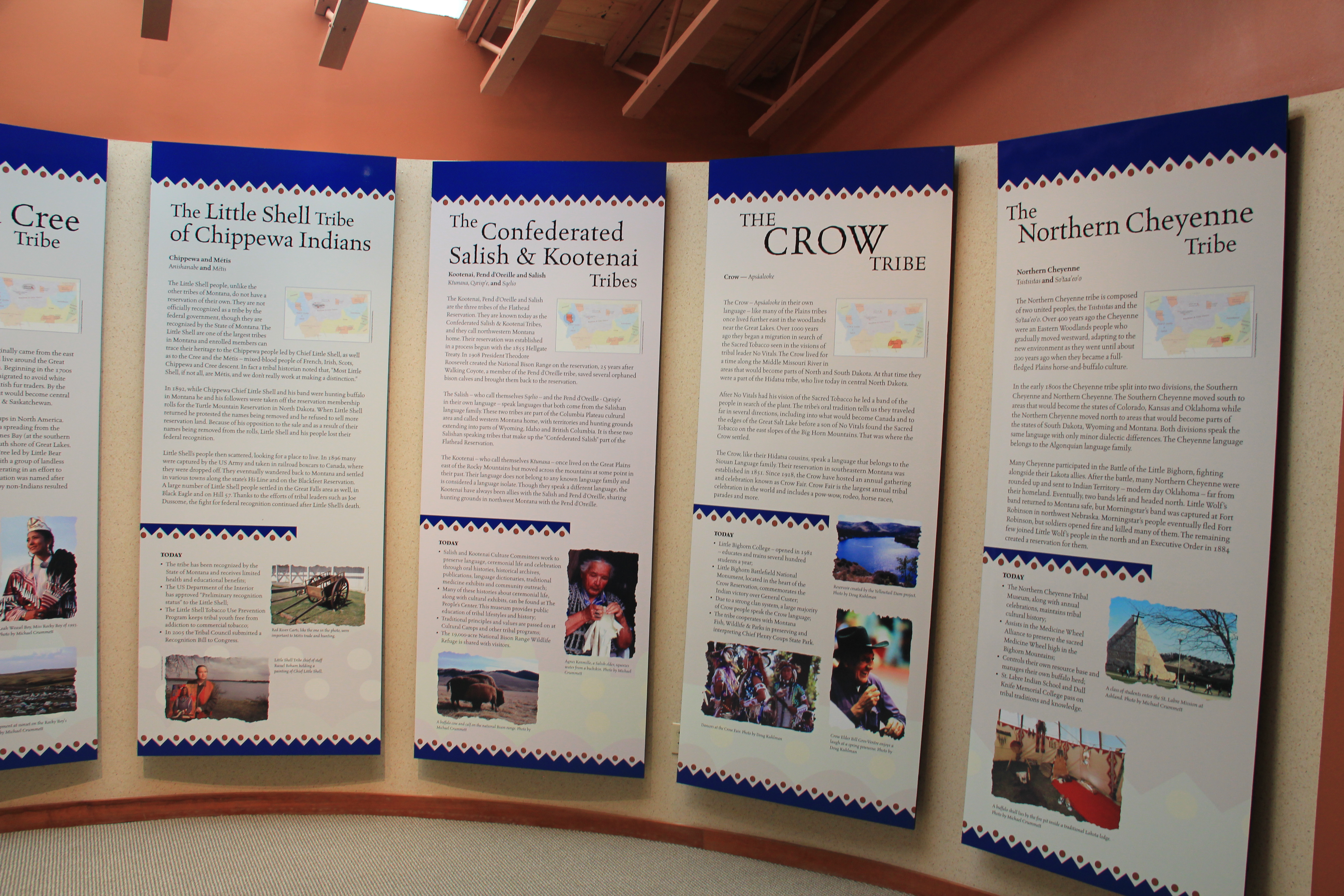

The interpretive center is a model of 21st century Native American-focus history. It provides facilities and exhibits for visitors, and encourages a longer stay and exploration of the site. Park managers understood that this site had special significance to all Native Americans thus they included capsule history displays about all Montana tribes of today along with displays that emphasize the Native American dominance of the landscape when the jump was in use.

Park managers understood that this site had special significance to all Native Americans thus they included capsule history displays about all Montana tribes of today along with displays that emphasize the Native American dominance of the landscape when the jump was in use.

As the park was being expanded and improved into an effective heritage asset, both in its public interpretation and visitor facilities, research on the property continued. The buffalo jump is now considered the largest in the United States, and quite likely the world. In the summer of 2015, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark as one of the nationally significant archaeological and Native American properties in America. The bone deposits remain deep and rich in artifacts, still awaiting further exploration despite being mined for a brief time during World War II for phosphorus production. Indeed the entire site is one of reflection and respect for the cultural contributions made by the First Nations long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark just over 200 years ago.

As the park was being expanded and improved into an effective heritage asset, both in its public interpretation and visitor facilities, research on the property continued. The buffalo jump is now considered the largest in the United States, and quite likely the world. In the summer of 2015, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark as one of the nationally significant archaeological and Native American properties in America. The bone deposits remain deep and rich in artifacts, still awaiting further exploration despite being mined for a brief time during World War II for phosphorus production. Indeed the entire site is one of reflection and respect for the cultural contributions made by the First Nations long before the arrival of Lewis and Clark just over 200 years ago. Here is a property that today tells us how the earliest Montanans used their wits and understanding of nature and landscape to enrich their diet and to make their world, one far from that of our own, and one still difficult for those of us in the 21st century to grasp.

Here is a property that today tells us how the earliest Montanans used their wits and understanding of nature and landscape to enrich their diet and to make their world, one far from that of our own, and one still difficult for those of us in the 21st century to grasp. This buffalo jump remains a place of mystery and meaning, and when you look to the south and see the shadow of Crown Butte you glimpse into that world of the deep past in Montana,. If you look in an opposite direction you find the patterns of settlement that surround this sacred place. And that is where we go next to St. Peter’s Mission and the Sun River Valley.

This buffalo jump remains a place of mystery and meaning, and when you look to the south and see the shadow of Crown Butte you glimpse into that world of the deep past in Montana,. If you look in an opposite direction you find the patterns of settlement that surround this sacred place. And that is where we go next to St. Peter’s Mission and the Sun River Valley.