Saco, a small Great Northern Railway town on Montana’s Hi-Line in Phillips County, is a good place for comparison photography from the historic preservation planning work of 1984 to my return trip in 2013.

As I worked across the state in the winter and spring of 1984, my schedule and route was mostly self-driven: choices on how much I wanted to see and in what depth were left to me. But the State Historic Preservation Office wanted me to take a particular close look at Saco because several citizens and property owners were turning to historic preservation and no one at the office in Helena really knew what the town looked like.

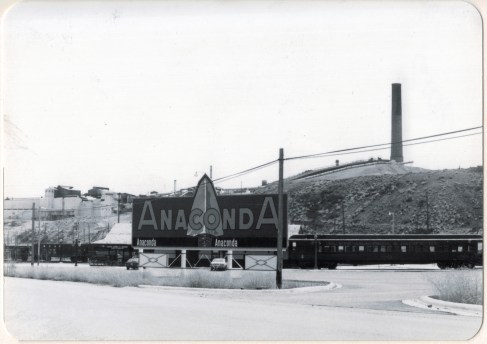

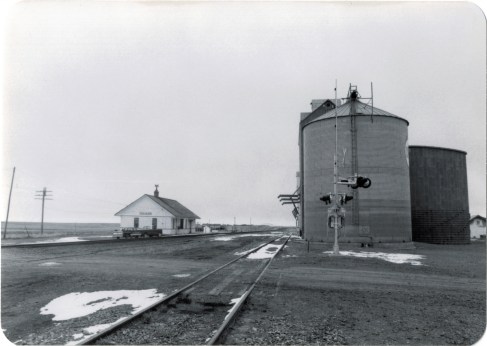

Saco at first glance was similar to many other Hi-Line railroad towns that were not county seats. It had a T-town plan, that is the primary commercial artery faced the tracks (that was the route of US 2) while a secondary commercial street radiated like the stem of a T from the center of the town. Saco then still had a Great Northern depot, one of the standardized small designs from the 1950s. Across from the depot on the highway was the Clack Service Station, where I bought gas that morning. The service station was later listed in the National Register as part of the effort to identify key roadside architecture along US 2: the station now serves as a visitor center.

But in 1984 no one in Saco talked about roadside architecture. The focus was on an early 20th century two-story bank building. Many Montana railroad towns have similar buildings–really landmarks of capital, then and now. They spoke to the promise of the town–and were always located on the prominent corner (here the point of the T) facing the tracks. No one who passed through Saco and bothered to take a look would doubt that local residents believed in the community because there was the architecturally impressive bank building, commanding respect on the plains landscape by its mere presence.

Saco was different than other communities because the opposite corner from the bank was also occupied by an architecturally notable two-story commercial block, and today both of those buildings remain as physical anchors of the town’s early 20th century history.

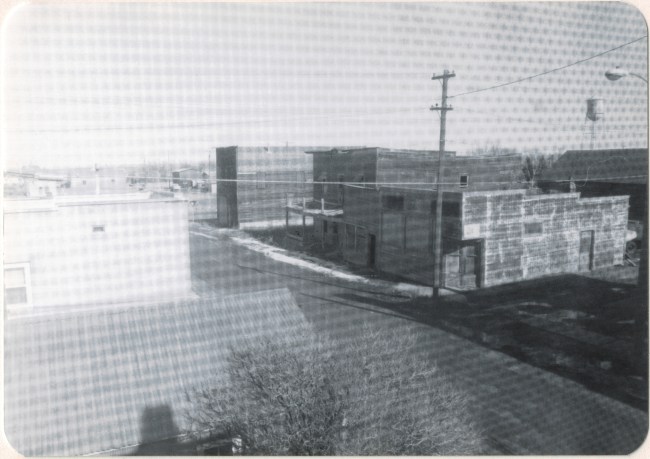

However, the commercial buildings that once lined the stem of the T are missing. Here is a view from a window in the second floor of the bank building that show some of the buildings.

One old hotel was barely hanging on in 1984 as these two photos show. and residents wanted to keep it, but now those are gone and the block behind the bank and the commercial block have been wiped clean.

Other one-story buildings on the highway have also been demolished to make way for new prefab structures, but on the streets behind US 2 a good bit of historic Saco remains, from lodge buildings to garages.

Saco in 1984 even had a historic attraction–the one-room school that Chet Huntley attended when he grew up in this part of Phillips County in the early 20th century. In 1984 the Huntley school was worthy of a stop–because of the fame of Chet Huntley, who also wrote well of the place in his memoirs. But now few stop to look, I was told–because no one recalls who Chet Huntley was. He was a legendary newsman of his time, and his NBC program once ruled the airwaves. Then CBS named Walter Cronkite as its evening news anchor. He is the name people still speak of in the 21st century. Chet Huntley has been forgotten.

My last stop in Saco in 1984 brings this brief narrative to a happy ending. One resident wanted to show off his home–an attractive bungalow. We explored the place and looked over the blueprints–from Sears Roebuck–that his family used to build the place in the second decade of the 20th century. 100 years later, the house remains, as attractive as ever.

Families remain devoted to Saco, and while its time as a commercial stop is diminished from the early 20th century it remains a community adding new layers of history to this place on the Hi-Line.