It would not be unfair to suggest that, perhaps, Montana has too many highway history markers. There are the classic ones of the mid-20th century by the state highway department with wonderful silhouettes from Helena artist Shorty Shope, as shown above.

Then there are hundreds of contemporary interpretive markers everywhere—markers that you just didn’t see back at the time of my historic preservation plan survey of 1984.

But early in that survey work in March 1984 I encountered along Highway 16 in Roosevelt County a sign that marked an “Agricultural History Site” crediting farmer Ira Jensen McCabe for the northern plains’ first “grass barrier applied to farmland.”

Ever since that encounter, I have been fascinated by Montana’s handmade history signs. Here are some of my favorites.

In Big Timber this marker (above) about Captain William Clark was on old U.S. Highway 10 until 1983 when it was moved to the city park of Big Timber. It was fresh and somewhat shiny then—40 years later it’s a bit worse for wear.

At the town park of Grass Range in Central Montana residents shared their history at some depth. This place is not on Highway 200 and it’s almost like the 1983 sign is there to remind residents of their past—then you find out that the park was where the community celebrated its 100th anniversary in 1983.

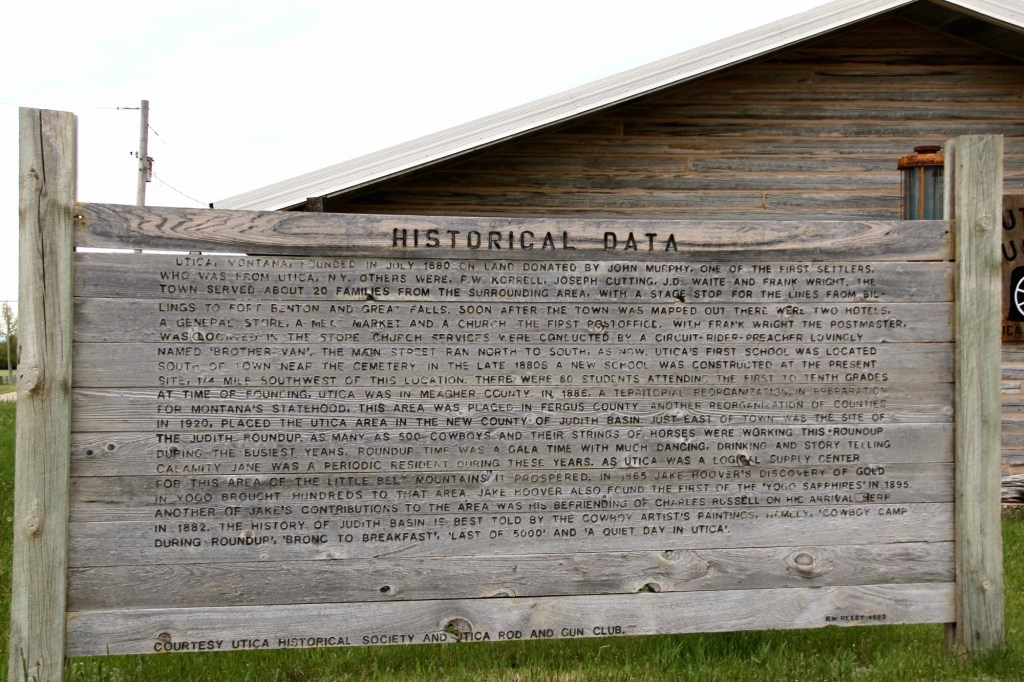

Grass Range seems concise and to the point compared to the Historical Data marker at Utica crafted by R.W. Reedy in 1980 for the Utica Historical Society and the Utica Rod and Gun Club.

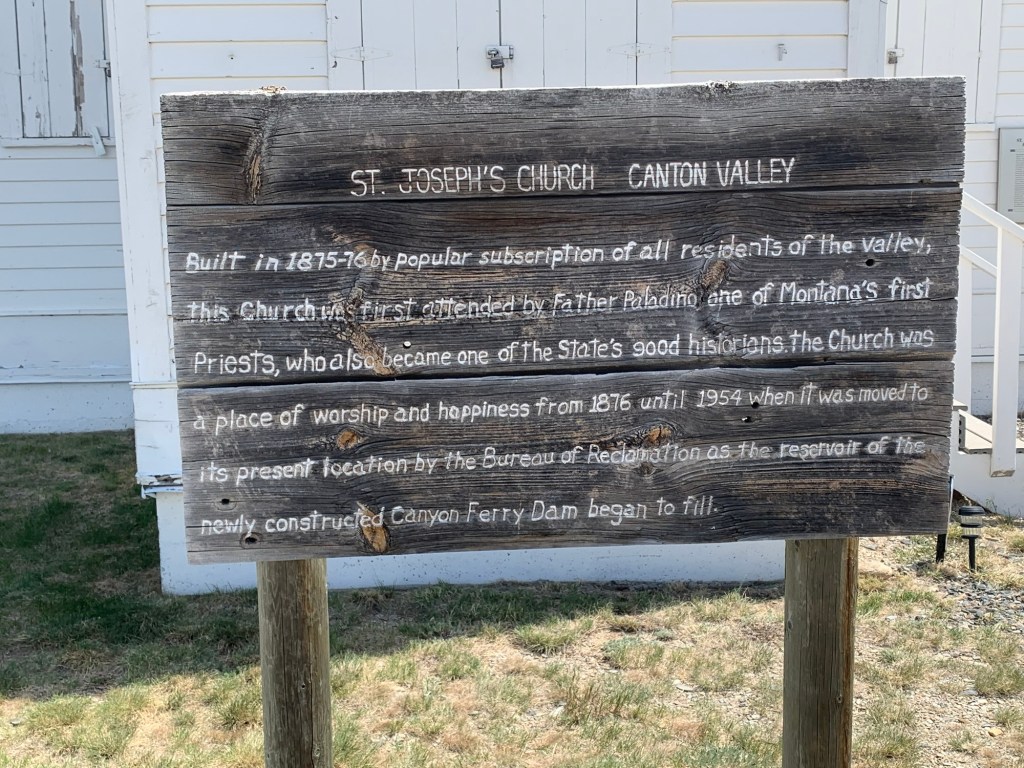

Sometime after 1954, residents of Broadwater County added the marker below about the history of St. Joseph’s Catholic Church.

The Martin family explained the story of Our Lady of the Little Rockies” (below) outside of Hays in Blaine County.

My favorite, however, is in Chouteau County along old Highway 87. It tells the story of Verona, one of the many homestead era towns that once covered Central Montana. The marker serves as a roadside stop but it’s not for tourists as it’s far from the present highway. It serves as a tribute to the past, complete with a painting of what Verona was like more than 100 years ago.

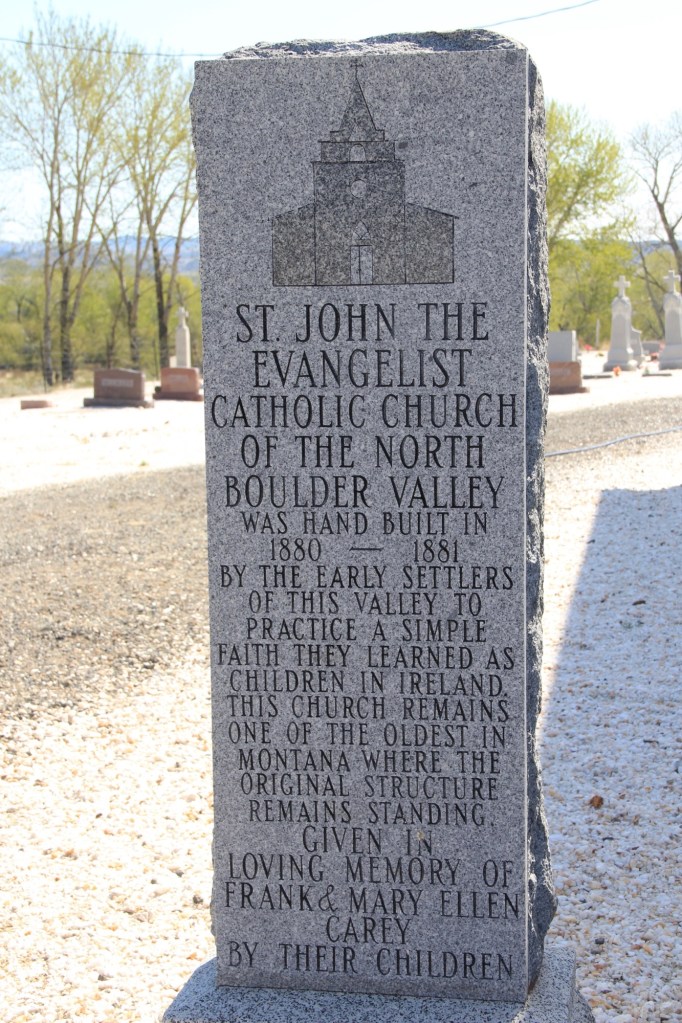

Handmade history hasn’t disappeared, but it does take different forms, such as a permanent stone marker for St John the Evangelist Catholic Church in the Boulder Valley (below) put up by the Carey family.

Or the interpretive marker for local history at Sula, in the state’s southwestern tip. Ranches have gotten into the act as well as seen by this wooden sign (below) about the location of Meriwether Lewis on August 12, 1805.

Montanans sharing stories about the places that matter to them—it doesn’t get more “public history” than this.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

Recently one of my graduate students from almost 20 years ago, Carole Summers Morris, contacted me. Carole had just discovered that her family had roots in Carter County, Montana–and she wanted to know if I had ever been in Ekalaka. I told her yes, in 1984, as documented by the postcard below I picked up on that trip, and most recently in 2013.

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

For Ekalaka itself, my 2014 post focused on public buildings such as the Carter County Courthouse and the historic elementary school. I did not include an image of the old town

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I mentioned the existence of the nursing home next to the county courthouse–an arrangement of space not seen elsewhere in the state–but did not include a photo of the c. 1960 Dahl Memorial Nursing Home.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

I didn’t even include all of the buildings at the excellent Carter County Museum, such as this well-crafted log residence from the early settlement period, the Allenbaugh Cabin, dated c. 1882-1883, probably the earliest surviving piece of domestic architecture in the county today. When I visited the museum in 1984, the cabin had been acquired but it was not restored and placed for exhibit until the late 1990s.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole.

When most people think of Ravalli County they think of the ever suburbanizing northern half, as you take U.S. Highway 93 south–a four lane highway–from Missoula and encounter the new suburbs of Florence. But if you use U.S. Highway 93 from the southern end, you find a very different place, one that starts with Ross’ Hole. There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.

There are few more beautiful places in the state, even on this cloudy day in 2012, the hole beckoned, as it has for centuries. In western American history, its importance has multiple layers, from ancient Native American uses to the peaceful encounter between Flathead Indians and the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1805. Without the horses the expedition acquired from the Flathead, its journey would have been much more difficult, if not impossible. Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley.

Montana “cowboy” artist Charles M. Russell painted the scene as a prominent historical mural in the House of Representatives chamber at the Montana State Capitol in 1912. His composition, as I used to like to point out when I gave state capitol tours in 1982, emphasized the centrality of the Native Americans in the region–the expedition were minor characters, in the background of the painting’s right side. The place name Ross’s Hole refers to Hudson Bay Company trader Alexander Ross who traded there in 1824. Hole was a trader and trapper term for mountain valley. At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

At the time of the 1984 survey, Ross’ Hole was interpreted by this single wooden sign, now much worse for the wear of the decades. But like many important landscapes in the state, today you find a rather full public interpretation in a series of markers sponsored by the Montana Department of Transportation, the U.S. Forest Service, and the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93.

Any trip to Ross’ Hole would not be complete with a stop, however brief, at the roadside architecture-a log bungalow–home to the Sula Community Store, which can basically provide you with about anything you might need while traveling on U.S. Highway 93. And the coffee is always hot, and strong.

And the coffee is always hot, and strong.