Dominated by the monumental Cruse family mausoleum, Resurrection Cemetery has been a Montana Avenue landmark for over 100 years. It is not the first Catholic cemetery in Helena–the original one was nearer the yards of the Northern Pacific Railroad and was closed c. 1906-1908, when Resurrection Cemetery was under development. The first cemetery became abandoned and many markers and crypts were not removed until the late 1940s and 1950s. Then in the 1970s, the city finished the process and turned the cemetery into Robinson Park, where a small interpretive marker still tells the story of the first Catholic cemetery.

Resurrection is a beautifully planned cemetery, with separate sections, and standardized markers, for priests and for the sisters, as shown above. Their understated tablet stones mark their service to God and add few embellishments. Not so for the merchant and political elite buried in the historic half of Resurrection Cemetery. “Statement” grave markers abound, such as the Greek Revival temple-styled mausoleum for the Larsen family, shown below.

An elaborate cross marks the family plot of Martin Maginnis, an influential and significant merchant and politician from the early decades of the state’s history (but who is largely forgotten today). Nearby is the family plot for one of Maginnis’ allies in central Montana and later in Helena, T. C. Power.

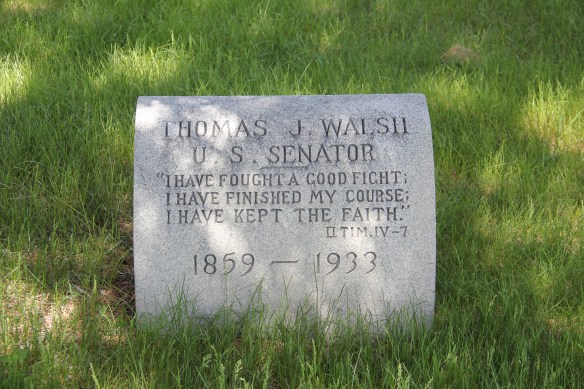

Joseph K. Toole, a two-time Governor of Montana, is also buried with a large but not ornate stone marker, shown below. Former senator Thomas Walsh is nearby but what is

most interesting about the Walsh family plot is the striking Arts and Crafts design for his

daughter Elinor Walsh, who died as a young woman. I have not yet encountered a marker similar to hers in all of Montana.

Another compelling marker with statuary is that of another young woman rendered in marble, a memorial to James and Catherine Ryan.

Another compelling marker with statuary is that of another young woman rendered in marble, a memorial to James and Catherine Ryan.

Thomas Cruse, who struck it rich with the Drumlummon mine at Marysville, had no qualms about proclaiming his significance and the grandest cemetery memorial in Montana bears his name. Cruse already had put up at least one-third of the funding for the magnificent High Gothic-styled St. Helena Cathedral in downtown Helena. At Resurrection, Cruse (who died in late 1914) was laid to rest in a majestic classical-style family mausoleum where his wife and his daughter were also interred (both proceeded Cruse in death). The Cruse mausoleum is the centerpiece of Resurrection’s design.

But the monuments for the rich and famous at Resurrection are the exceptions, not the rule. In the historic half of the cemetery, most markers are rectangular tablet types. The cemetery also has a separate veterans section.

But my visit on Memorial Day 2018 left me with the feeling that the cemetery is an under-appreciated historic property. There are no signs of true neglect, but it was so quiet on Memorial Day that I did think the place had become an almost forgotten historic asset–an afterthought in today’s busy world. I hope not–because this cemetery has many jewels to explore and appreciate. Perhaps the most striking–certainly most rare to see–are the cast iron baskets–or bassinets, see below, that surround two children’s graves.

But my visit on Memorial Day 2018 left me with the feeling that the cemetery is an under-appreciated historic property. There are no signs of true neglect, but it was so quiet on Memorial Day that I did think the place had become an almost forgotten historic asset–an afterthought in today’s busy world. I hope not–because this cemetery has many jewels to explore and appreciate. Perhaps the most striking–certainly most rare to see–are the cast iron baskets–or bassinets, see below, that surround two children’s graves.

plots–certainly the ironwork was a status symbol in the late 19th century and there is no one statement. Families adorned their graves with fences much as they surrounded their houses in the nearby neighborhoods.

plots–certainly the ironwork was a status symbol in the late 19th century and there is no one statement. Families adorned their graves with fences much as they surrounded their houses in the nearby neighborhoods.

Benton Avenue Cemetery is worth a new consideration for its many different forms, materials, and designs. When I lived in Helena some thirty-five years ago, I gave it scant attention–it deserves so much more.

Benton Avenue Cemetery is worth a new consideration for its many different forms, materials, and designs. When I lived in Helena some thirty-five years ago, I gave it scant attention–it deserves so much more.

The date of most markers are from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. Mostly made of granite and sandstone, with some marble as well, the grave markers reflect Victorian styles and Classical influences. Herman Gans’ marker from 1901, seen below, is a mixture of both.

The date of most markers are from the late 19th century to the early 20th century. Mostly made of granite and sandstone, with some marble as well, the grave markers reflect Victorian styles and Classical influences. Herman Gans’ marker from 1901, seen below, is a mixture of both.

The looming presence of the school grounds is a worry for future preservation of the cemetery–could it be possibly overlooked, ignored, and abandoned? One online resource about the cemetery remarks that there are more Jews buried in the cemetery than live in Helena today. But this sacred place is a powerful reminder of the contributions of the Jewish community to Helena’s growth and permanence. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the cemetery should be valued as one of the city’s oldest and most significant historic properties.

The looming presence of the school grounds is a worry for future preservation of the cemetery–could it be possibly overlooked, ignored, and abandoned? One online resource about the cemetery remarks that there are more Jews buried in the cemetery than live in Helena today. But this sacred place is a powerful reminder of the contributions of the Jewish community to Helena’s growth and permanence. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places, the cemetery should be valued as one of the city’s oldest and most significant historic properties.

Fort Kipp Cemetery, above, is one of those place, nestled on the river bluffs overlooking the Missouri River. On a larger scale but still intimate, personal, and compelling is the city cemetery of Red Lodge, hundreds of miles away. Here surrounded by the mountains

Fort Kipp Cemetery, above, is one of those place, nestled on the river bluffs overlooking the Missouri River. On a larger scale but still intimate, personal, and compelling is the city cemetery of Red Lodge, hundreds of miles away. Here surrounded by the mountains

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

The Montana State Capitol was my first heritage project in the state–the Montana Department of General Services worked with the Montana Historical Society to have me prepare an interpretive guide to the capitol, and then set up the interpretation program, following an excellent historic structures report prepared by the firm of Jim McDonald, a preservation architect based in Missoula.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

When I worked at the capitol, of course I passed daily by other state government buildings, and rarely gave those “modern” buildings another thought, except perhaps for the museum exhibits and archival collections at the Montana Historical Society. Years later, however, what seemed unbearably recent in the early 1980s were now clearly historic. One of my MTSU graduate assistants, Sarah Jane Murray, spent part of a summer last decade helping develop a inventory of the buildings and then, finally, in 2016 the Montana State Capitol Campus historic district was listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire.

The Capitol Annex (1910) was the first building added to the capitol campus, and its restrained classicism came from the firm of Link and Haire. The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects.

The nearby Livestock Building (1918) is like the annex, complimentary of the capitol’s classicism but also distinguished in its own Renaissance Revival skin. Link and Haire were the architects. The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena.

The mammoth Sam W. Mitchell Building (1948-50) reflected the post-World War II interpretation of institutional modernism and its mammoth scale challenged the capitol itself, especially once a large addition was completed at the rear of the building in 1977. The architect was Vincent H. Walsh of Helena. Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.

Another Link and Haire building on the campus is the Board of Health Building (1919-1920), which continues the pattern of more restrained architectural embellishment that shaped the look of the government buildings in the middle decades of the century.  The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings.

The Cogswell Building (1954-55, 1981) is another Vincent H. Walsh design, again reflecting the stripped classicism institution style often found in Cold War era public buildings. While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959.

While the capitol campus took form on a hill about a mile east of Last Chance Gulch, the state’s governor still lived downtown, in the Queen Anne-style “mansion” originally built by miner and entrepreneur William Chessman and designed by the St. Paul firm of Hodgson, Stem and Welter. The state acquired the house in 1913 to serve as the residence for the governor and his family, and it remained the governor’s “mansion” until 1959. It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day.

It was the opportunity to be the curator of this house museum that attracted my newlywed wife Mary Hoffschwelle that led me to come with her to Montana. She was born in Billings; I had never been west of Dallas. But then over 25,000 miles of driving, visiting, and looking in Montana transformed me, and led not only to the 1986 book A Traveler’s Companion to Montana History but now this Montana historic landscape blog. Fate, perhaps. Luck–I will take it any day. Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena, the capitol city of Montana, was where I made my home from 1981 to 1985, and served as my base for travels far and wide across the state during my work for the Montana State Historic Preservation Office’s preservation plan in 1984-1985. I started the project at the 1950s modernist Montana Historical Society building next door to the state capitol.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

Helena then was a small town but a big urban environment, and I used to enjoy exploring its two sided urban landscape: the 1970s “Last Chance Mall” where planners and designers closed the street for a few blocks and inserted a pedestrian mall, thinking that a “walking mall” experience would keep businesses downtown, and then the rest of the downtown before urban planners decided to change it into something it never was.

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The impetus behind the urban renewal of the 1970s was not only federal dollars through the Model Cities program but also federal presence. Officials wished to anchor the new Last Chance Gulch Urban Renewal project with a Park Avenue section that

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

The pedestrian mall on its west side ends at the imposing Richardsonian Romanesque styled T.C. Power Block, one of my favorite commercial buildings not just in Helena but in all of Montana.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

This downtown has several architectural landmarks, as you see below with the Art Deco-styled First National Bank building, and then a short block away, a magnificent statement of power and influence, the Montana Club, designed by noted architect Cass Gilbert.

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown

Once you cross Neill Avenue, you enter a new downtown of 21st century Helena, created by the demolition of the historic Great Northern Railway passenger station in the 1990s and the construction of a new Federal Reserve Bank. Here suddenly was a new downtown anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

anchor, similar to that of the 1977 Federal Building on the opposite end of Last Chance Gulch. And the name given to this? the Great Northern Center, where not only the

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more

Federal Reserve lived but also a huge new Federal Courthouse, the Paul G. Hatfield Courthouse (2001-2002), a neoclassical monument of a scale that Helena had not seen since the construction of the State Capitol more than a century earlier, along with its more modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.

modern styled neighbor, the Senator Max Baucus Federal Building. In less than 40 years, the federal presence not only moved from one end of the gulch to another, it had become much larger and architecturally distinct.