In my 1984 fieldwork, Havre was a base for quite a bit of travel along the Hi-Line. One of the most compelling landscapes, and among my favorites for the state, were the little towns, regularly spaced about every eight miles, west of Havre.

At the time, my understanding of this landscape was heavily influenced by recent works by the American Studies scholar John Stilgoe (Metropolitan Corridor: Railroads and the American Scene) and the historical geographer John Hudson (a series of articles that culminated in the book Plains Country Towns.) Stilgoe reminded me that railroads in the late 19th century not only defined towns and urban design but impacted American culture in how small, tiny spaces became part of urban, metropolitan life through the steel tracks. Hudson explain why towns existed every six to seven miles or so throughout the plains (these were often single track lines so trains needed places to pull over for passing, and places where water and fuel could be acquired as necessary). Hudson explained differences between railroad division points, where shops and offices would be located, and “country towns,” where typically a combination depot carried out all of the railroad’s corporate functions.

This arrangement of space, and the ennobling of railroad culture in larger towns, was exactly what I saw in Havre and Hill County. Ever since 1984, this has been among my favorite places in Montana. In a posting last year I discussed the “disappearing depots” along the Hi-Line, focusing on west Hill County. I want to revisit those same places today, with a deeper view on what was there in 1984 and what you find today.

Inverness, established c. 1909, was the first place I stopped but spent little time there because already in 1984 its Great Northern depot was gone. But in 2013, I was looking for beyond the Stilgoe-Hudson way of understanding plains country towns. Inverness in 2010 had 55 residents, but still held several early settlement landmarks, such as its early 20th century elevators along the railroad, a National Register-quality c. 1920 store/gas station, and two large two-story frame blocks–the historic Inverness Hotel (most recently Inverness Supper Club) dates to the second decade of the 20th century.

The Sacred Heart Catholic Church dates to the town’s beginnings, but a brick school from 1931 with 1952 additions closed in the early 21st century.

Inverness’s c. 1960 post office is a great example of stone-faced standardized design that the postal service used in small towns across the nation in that decade. It was one of the offices threatened with closure in 2011.

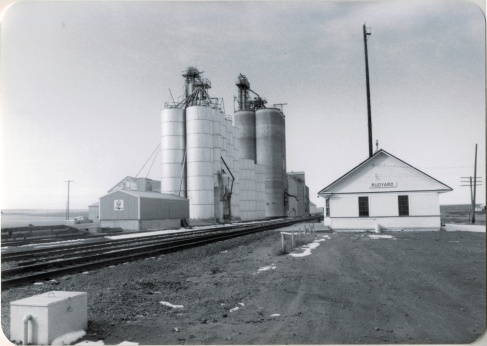

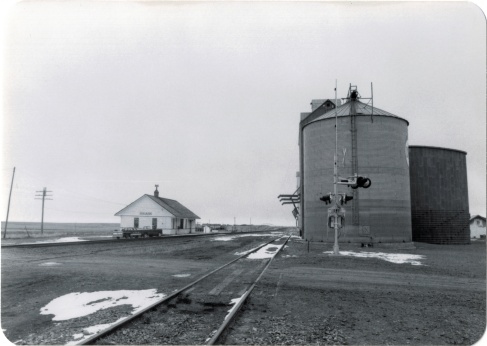

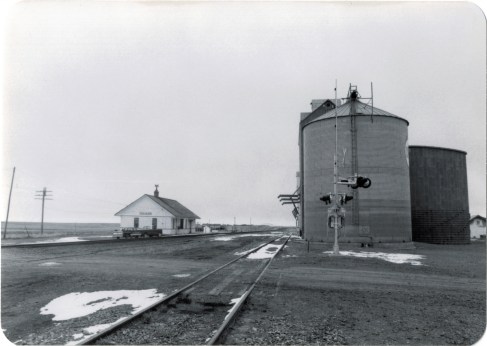

Rudyard, established 1909, was the largest of the west Hill County towns, about 500 people in 1980 but now with only 258 residents according to the 2010 census. Its prominence in the second half of the 20th century is reflected in two buildings: the tall concrete grain elevators along the railroad and the contemporary-styled Wells Fargo bank building on the prominent town corner facing the tracks and Reed Street.

Thirty years ago, as the construction of a modern bank building attests, several stores and the Hi-Line Theater were hubs of activity; today most businesses are closed.

Museums now abound–with the moved depot forming a small building zoo while an early 20th century stone building has become an auto museum.

Rudyard also has one of the highway’s most famous town signs–boasting of a population now greatly diminished but the old sorehead remains–at the Sorehead Cafe in the heart of the four block long commercial district.

One hundred years ago, Hingham (1910) seemed to be the town that would make it. From the railroad corridor several blocks of commercial businesses were filled in the next decade.

There was a town square featuring a city park in the midst of it all.

Here the town’s Commercial Club hosted the Hi-Line Fair, which “presented farmers and ranchers with an opportunity to exhibit their grain and livestock and to exchange ideas with people from other points along the Hi-Line.”

While the buildings, outside of the brick neo-classical brick bank (1913-14), were frame, town boosters were confident these were only the initial businesses. But the second decade of the 20th century proved to be the town’s high point, and frame buildings still define local businesses.

In 1930 they defined the town with a large, handsome two-story brick school at its south end (near U.S. 2, a recognition of the highway’s importance in getting students to and from Hingham).

The Our Lady of Ransom Catholic Church is a modernist landmark, and one of the most architecturally important buildings of the Hi-Line, part of the Great Falls diocese effort to improve and modernize its churches in the mid-20th century. A much earlier frame Methodist Church remains, and has most recently served as a community chapel.

The boosters of Gildford also had high hopes in 1910 and the homesteading boom brought a full fledged town into existence by 1915-16.

The boom decade is marked by the extant Gildford State Bank (1914), which also served as the town’s post office when I first visited in 1984. The town also had an early industry, the Mundy Flour Mill.

Kremlin acknowledges its distinct name with its highway town sign.

Settlement began in 1909, with a plat from land agent K.C. Farley, focused on the Great Northern section house, later replaced by a standardized depot, all of which is gone from the railroad corridor today.

The WPA built a new high school in 1938, which remains a central landmark for the community, a symbol of the future, and a good way to end this posting.