When the state government in 2014 identified 18 businesses that had been operating in Montana for at least 100 years, the Malta Cemetery was one of those 18. The Manitoba Road, the precursor to the Great Northern Railroad, established a siding here in 1887. Three years later, a post office named Malta was established and settlement followed.

Then came the homesteading boom of the early 1900s. The town of Malta was formally established in 1909. The cemetery association—still a private corporation headed by three trustees today—came soon thereafter.

The cemetery is north of the town center at a place where first burials date to 1894. The cemetery design centers on a tree-lined road that reaches the top of a slight rise, with different roads radiating on either side of the main artery. It is not an elaborate design but the many trees planted in its early years give the place a calm, serene feel.

Several large, expressive stone markers identify town founders and the first generation of leaders. the Malta Enterprise of March 30, 1916, recorded the passing of Benjamin W. “Brock” Brockway, who was the town mayor, and a cemetery trustee. The newspaper emphasized that Mayor Brockway “grew to be an intregal part of the growth and development of the city of Malta. His fathful [sic] services in the various city and county organizations and his long and intimate association with the affairs of the country’s complex life made him a valuable leader, a sate adviser and a most efficient officer. He was justice of the peace in Malta for a long time, secretary of the Milk River Valley Water Users’ Association for the success of which he worked with an unusual degree. He held the secretaryship of the Malta Cemetery association, and his never ceasing interest in and devotion to the improvement as a more fit sleeping. place for the dead were deeply appreciated everywhere.”

When Brockway first came to Malta, he worked for the town’s leader merchant, Robert M. Trafton, whose similar beautiful stone marker is nearby. Trafton is considered one of the town’s founders. He came in 1886 as the Manitoba Road was being completed. He traded extensively with Native Americans, paying $4 a ton for buffalo bones (according to the Billings Gazette of March 16, 1933). He made $30,000 by selling the tons of bones to fertilizer companies in the east. Later he was a founder of the First State Bank of Malta; its classical Revival building remains a town landmark.

Trafton died in Long Beach, CA, but wanted to be buried in Malta.

Brockway’s predecessor as Malta mayor was Arthur Cavanaugh, also a prominent businessman. He has a stone marker to the west of the Brockway and Trafton graves centered in a large concrete lined family plot.

William McClellan (d. 1916) was another important early Malta merchant. He and Lee Edwards built a two-story business block prominently facing the railroad tracks in 1910. It is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.

Isolated in a northwest corner is the monumental Phillips family plot that honors the county’s first family. The county was named for Benjamin D. Phillips, a rancher and miner and he is buried at Highland Cemetery in Havre. The Malta marker honors his son Benjamin M. Phillips, who ran his father’s interests in Malta, but especially Ben’s first wife Bessie Keller Phillips, who died in 1918 in a tragic fire at their home. She tried to repair a gas stove, but it exploded and Bessie died from the burns she suffered in the explosion.

Another noted Victorian style marker is for Timothy Whitcomb who was the brother of Zortman mine owner Charley Whitcomb. Timothy worked the properties at Zortman but contracted liver disease and died in Malta in early 1910. the Whitcomb plot also includes the burial of his wife Katie McGuire Phillips who died in 1937.

John Survant, a native of Missouri, was a State Senator, first elected in 1910. He also was a prominent businessman in both Malta and Hinsdale. Survant began as a partner of Edwards and McClellan but later bought out their interests. He owned a large ranch along the Milk River Project as well. He donated the land for the cemetery.

As the Survant markers indicate, at some point in the second half of the 20th century the cemetery association undertook a major renovation of the property, uprooting both gravestones and foot markers and installing them in long concrete rows.

The renovation perhaps made mowing and irrigation more efficient. It certainly gave the cemetery a unique look, one that I have not found in other early northern Montana cemeteries.

The Malta Cemetery also has several expressive grave markers placed over the last thirty years, such as the colorful river scene of Robert M. Ostlund’s marker (above) and the metal sculptures of a cattleman (Allan Oxarart) and a golfer (Jack D. Brogan), as shown below.

The Malta Cemetery is a fascinating blend of the old and new, and one of the oldest community institutions of the Hi-Line.

But my visit on Memorial Day 2018 left me with the feeling that the cemetery is an under-appreciated historic property. There are no signs of true neglect, but it was so quiet on Memorial Day that I did think the place had become an almost forgotten historic asset–an afterthought in today’s busy world. I hope not–because this cemetery has many jewels to explore and appreciate. Perhaps the most striking–certainly most rare to see–are the cast iron baskets–or bassinets, see below, that surround two children’s graves.

But my visit on Memorial Day 2018 left me with the feeling that the cemetery is an under-appreciated historic property. There are no signs of true neglect, but it was so quiet on Memorial Day that I did think the place had become an almost forgotten historic asset–an afterthought in today’s busy world. I hope not–because this cemetery has many jewels to explore and appreciate. Perhaps the most striking–certainly most rare to see–are the cast iron baskets–or bassinets, see below, that surround two children’s graves.

plots–certainly the ironwork was a status symbol in the late 19th century and there is no one statement. Families adorned their graves with fences much as they surrounded their houses in the nearby neighborhoods.

plots–certainly the ironwork was a status symbol in the late 19th century and there is no one statement. Families adorned their graves with fences much as they surrounded their houses in the nearby neighborhoods.

Benton Avenue Cemetery is worth a new consideration for its many different forms, materials, and designs. When I lived in Helena some thirty-five years ago, I gave it scant attention–it deserves so much more.

Benton Avenue Cemetery is worth a new consideration for its many different forms, materials, and designs. When I lived in Helena some thirty-five years ago, I gave it scant attention–it deserves so much more.

Far from the bustle and grime of the Richest Hill on Earth are the historic cemeteries of Butte. As I have said many times already in this blog, I rarely considered cemeteries during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. That was a huge mistake for Butte. The three historic cemeteries I wish to consider here–Mt. Moriah, St. Patrick’s, and B’nai Israel–document the city’s ethnic diversity like few other resources, reinforcing how groups survived in a city together although they often keep to their separate communities. But the cemeteries also have sculpture and art worthy of attention and preservation–they are outstanding examples of late 19th and early 20th cemetery art and craftsmanship in the United States.

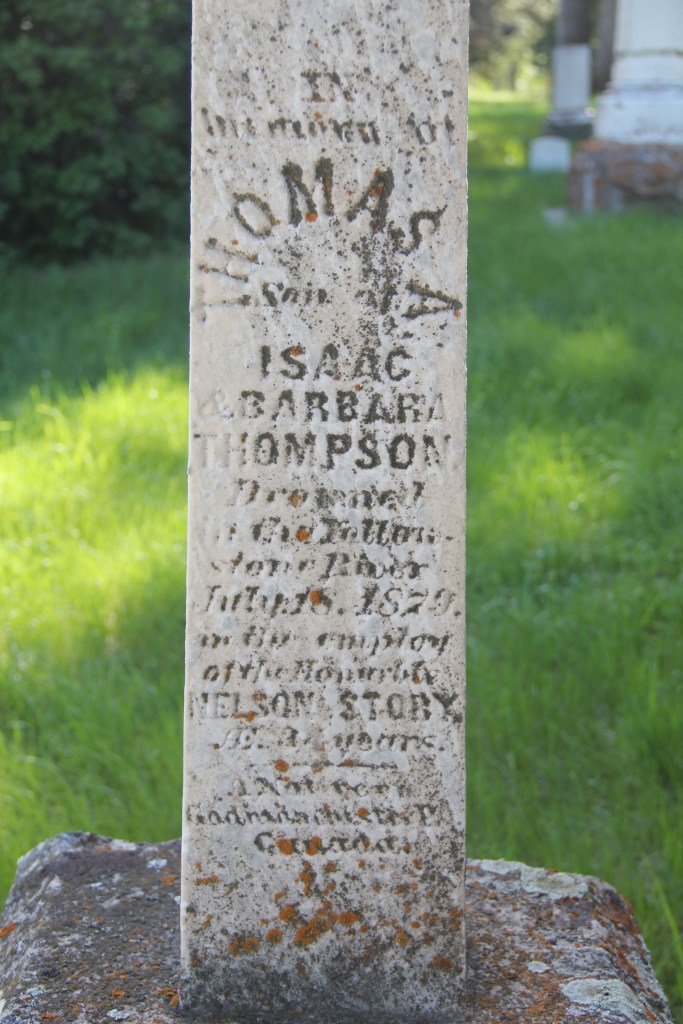

Far from the bustle and grime of the Richest Hill on Earth are the historic cemeteries of Butte. As I have said many times already in this blog, I rarely considered cemeteries during the 1984-1985 state historic preservation plan work. That was a huge mistake for Butte. The three historic cemeteries I wish to consider here–Mt. Moriah, St. Patrick’s, and B’nai Israel–document the city’s ethnic diversity like few other resources, reinforcing how groups survived in a city together although they often keep to their separate communities. But the cemeteries also have sculpture and art worthy of attention and preservation–they are outstanding examples of late 19th and early 20th cemetery art and craftsmanship in the United States. The Masons established Mr. Moriah Cemetery Association in 1877. The cemetery has many striking markers, especially the Thompson Arches (seen above and below), an elaborate statement to mark a family plot, especially when compared to the cast-iron

The Masons established Mr. Moriah Cemetery Association in 1877. The cemetery has many striking markers, especially the Thompson Arches (seen above and below), an elaborate statement to mark a family plot, especially when compared to the cast-iron

iron fence, when combined with the carving and detail of the gravestone itself makes quite the statement for Cornish identity in Butte at the turn of the century. Note the dual fraternal lodge marks, one for the Masons, another (the linked chain) for the Odd Fellows.

iron fence, when combined with the carving and detail of the gravestone itself makes quite the statement for Cornish identity in Butte at the turn of the century. Note the dual fraternal lodge marks, one for the Masons, another (the linked chain) for the Odd Fellows.

Frank Beck left this earth in 1909, and the marker for Frank and his wife Agnes is remarkable for the inclusion of the family pet, noted above as Frank and His Faithful Dog.

Frank Beck left this earth in 1909, and the marker for Frank and his wife Agnes is remarkable for the inclusion of the family pet, noted above as Frank and His Faithful Dog.

1881 when the Hebrew Benevolent Association first acquired the land from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Congregation B’nai Israel acquired the property in 1905, two years after finishing its landmark synagogue in uptown Butte.

1881 when the Hebrew Benevolent Association first acquired the land from the Northern Pacific Railroad. Congregation B’nai Israel acquired the property in 1905, two years after finishing its landmark synagogue in uptown Butte.

The cemetery seems to stretch to the very edge of the city, but it is worth a long walk around for what you can discover about the Catholic impact on Butte in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The cemetery seems to stretch to the very edge of the city, but it is worth a long walk around for what you can discover about the Catholic impact on Butte in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There are spectacular sculptural monuments to prominent city builders, such as the Classical Revival-style temple crypt for merchant price D. J. Hennessy.

There are spectacular sculptural monuments to prominent city builders, such as the Classical Revival-style temple crypt for merchant price D. J. Hennessy. Adjacent are separate plots maintained for Sisters who served and died in Butte as well as larger, more elaborate memorials for priests who served in Butte over the years.

Adjacent are separate plots maintained for Sisters who served and died in Butte as well as larger, more elaborate memorials for priests who served in Butte over the years.