Standard histories tell you that Cut Bank, the seat of Glacier County, dates to 1891. But significant numbers of permanent settlers did not arrive until the first years of the 20th century, following a major investment by the Great Northern Railroad to build a huge steel bridge and railroad offices, shops, and a roundhouse. The Fort Benton River Press on February 12, 1901, reported that “Cut Bank is rapidly assuming a metropolitan appearance.”

The initial railroad boom soon slowed until the homesteader movement brought new growth. In 1911 town officials agreed to discuss the creation of a permanent town cemetery with state officials. Between 1911 and 1914 citizens formed the Crown Hill Cemetery Association and the first documented burials in the local newspaper took place in 1914.

Located north of town the cemetery is on a slight rise and has an impressive view of Cut Bank to the South. A small lake is the focus of the cemetery plan.

Otherwise the cemetery contains long rows in a rectangular manner and there are few huge grave markers, instead many dignified and subtly designed markers cover the grounds.

There are several interesting markers and many note a fraternal lodge association.

The Halvorson marker dates to be death of Mrs. Harry Halvorson who died in 1924. At that time her funeral was the largest ever held in Cut Bank. The Midland Empire of April 22, 1924 reported that 650 attended the funeral and that 77 cars went from the town Masonic Hall to the cemetery. A member of the Rebekah lodges in both Cut Bank and Shelby, Halvorson’s funeral attracted other lodge members from Shelby, Conrad, Valier and Browning. Her husband was the senior member of the Halvorson mercantile company, which started in 1901.

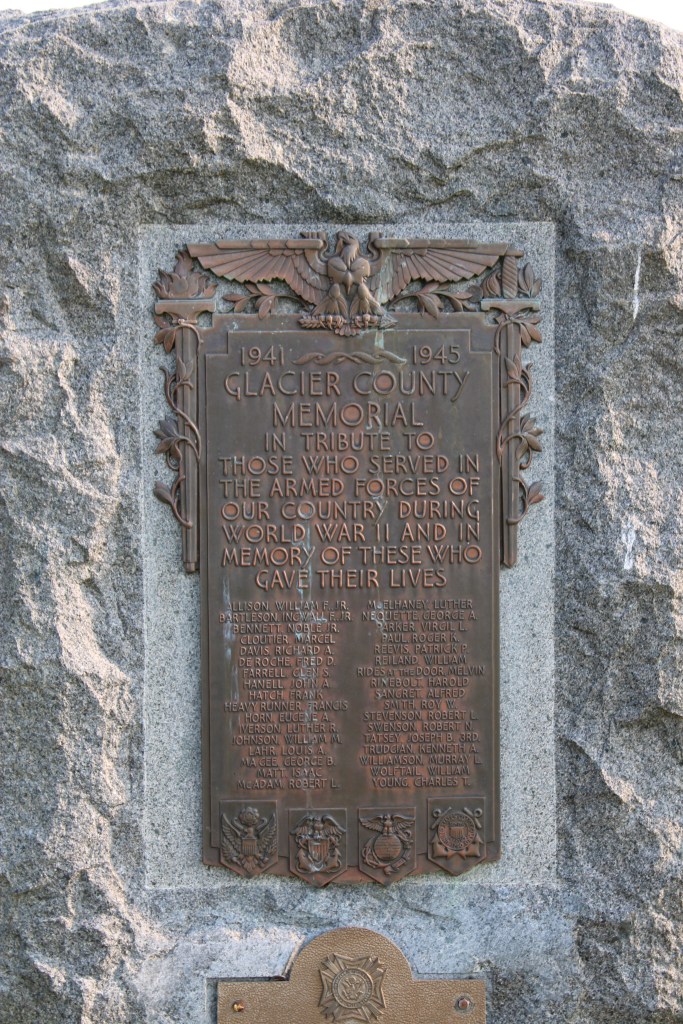

Another important marker is the veterans memorial from World War II. Cut Bank played a significant role as a satellite air field for the Great Falls Army Air Base. In 1942-43 pilots trained here in flying the B-17 Flying Fortresses. In 1948 the army conveyed the base to the town for civilian use.

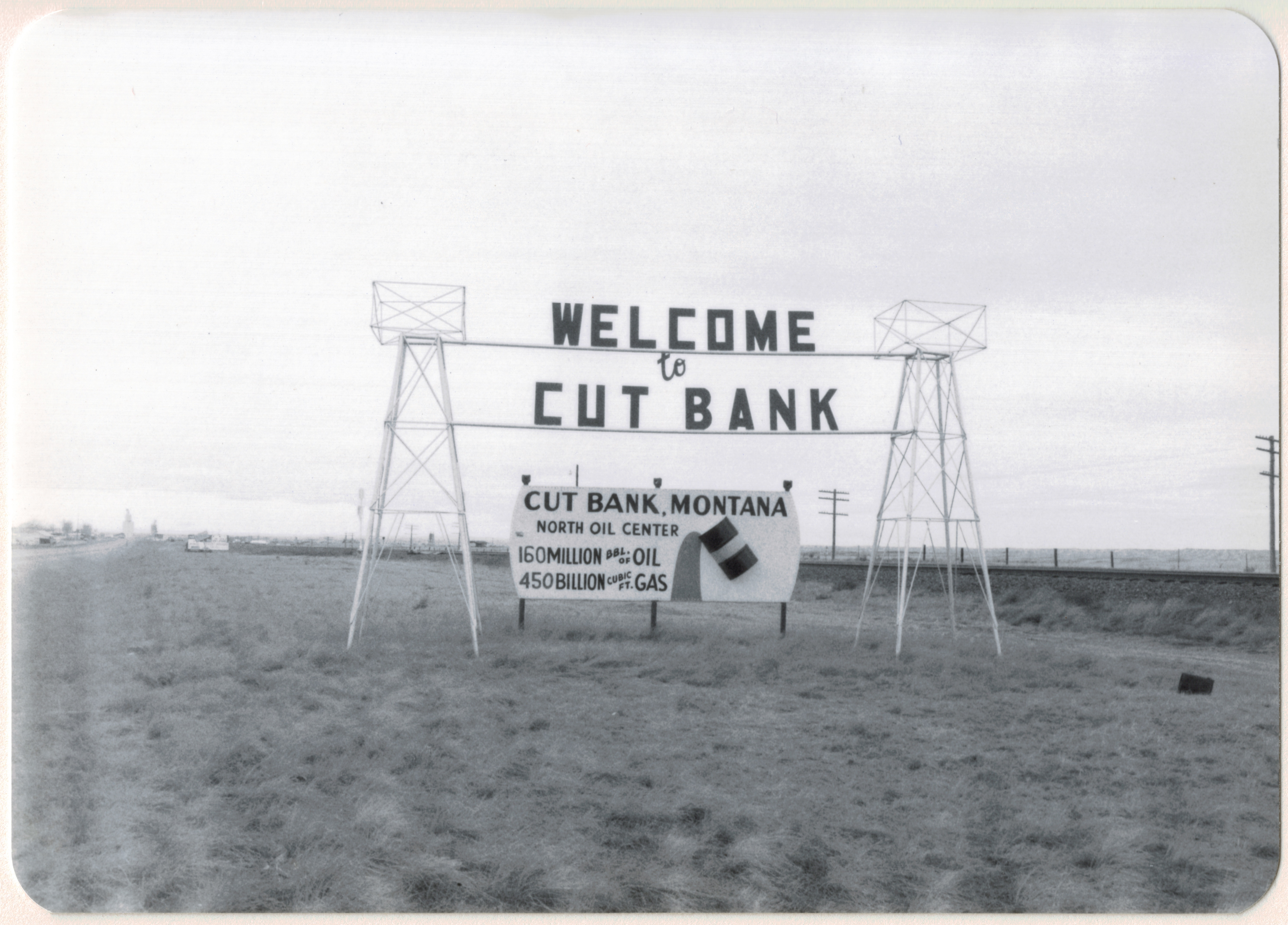

Perhaps an unattended consequence of the military air base is that winter temperatures at Cut Bank was regularly available to national media, which played up the mage of Cut Bank as the coldest place in the lower 48 states. Cut Bank embraced the image, as this bit of roadside sculpture below attests. It stands at the eastern entrance into town on US Highway 2.

Crown Hill Cemetery is one of the oldest properties in Cut Bank open to the public. The cemetery is well maintained, well manicured and a testament to the respect and dignity local residents give to their past.

The last post addressed Montana’s famous ranching landscape. Intermixed with the ranches, especially in the eastern third of the state, is a very different landscape of technology, one of pumps, storage facilities, pipelines, and refineries–the oil landscape of 20th and 21st century Montana.

The last post addressed Montana’s famous ranching landscape. Intermixed with the ranches, especially in the eastern third of the state, is a very different landscape of technology, one of pumps, storage facilities, pipelines, and refineries–the oil landscape of 20th and 21st century Montana.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land.

I am speaking instead of the wide range of images and themes that visually interpret the town’s and county’s history. Finding public art murals about the open landscape once dominated by the Blackfeet Indians and the buffalo is not surprising–communities often embrace the deep history of their land. That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery.

That Cut Bank also has a large expressive mural about the Lewis and Clark Expedition is not surprising–murals about Lewis and Clark were installed across several towns during the bicentennial of the expedition in the first decade of this century. East of Cut Bank is Camp Disappointment, one of the more important sites associated with the Corps of Discovery. Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

Nor is it surprising to see communities commemorate their homesteading roots, and the importance of agriculture and cattle ranching.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

But I was surprised, pleasantly, by the number of murals that also documented the town’s twentieth century history, whether it is the magnificent steel trestle of the Great Northern Railway just west of the commercial core, or a mural that reminded everyone of the days when the railroad dominated all traffic here.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

It is this first half of the 20th century feel that the murals interpret–the era that actually built most of the historic buildings you find there today–that I find so impressive and memorable about Cut Bank, be it people on bicycles or what an old service station was like.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.

Space matters when you interpret the built environment, and these various murals reflect not only a sense of town pride and identity they also give meaning to buildings and stories long forgotten.