Kalispell is the seat of Flathead County, established on the Great Northern Railroad line in the 1890s. Today the city is the hub for commerce, transportation and medical care in northwest Montana. The Advisory Council on Historic Preservation designated it as a Preserve America community in recognition of its historic downtown and multiple National Register of Historic Places properties.

Certainly the town has many impressive late Victorian era buildings, like the County Courthouse, but this post focuses on a part of Kalispell’s historic built environment that doesn’t get enough attention—its buildings of modern 20th century styles.

The key town founder was C. E. Conrad and similar to how he started the town, you could also say he started the modernist traditions by commissioning his grand Shingle-style mansion from architect A.J.Gibson in 1895. Architectural historians consider the Shingle style, introduced by major American architects Henry Hobson Richardson and the New York Firm McKim, Mead, and White, to be an important precursor to the modernist buildings that would flourish in Kalispell during the 1930s.

Another important example of early modernist style is this local adaptation of Prairie house style, a form introduced and popularized by the designs of American master Frank Lloyd Wright.

Kalispell’s best modernist examples come from the 1930s to 1960s. In 1931 Brinkman designed the KCFW-TV building in a striking Art Deco style. It was originally a gas station but has been restored as an office building with its landmark tower intact.

The Strand Theatre closed as a movie house in 2007 but its colorful Art Deco marquee and facade remain, another landmark across the street from the History Museum which is housed in the old high school.

The Eagles Lodge (1948-1949) is an impressive example of late Art Deco style, especially influenced by the federal “WPA Moderne” buildings from the New Deal. G.D. Weed was the architect.

Then the town opened Elrod School in 1951. It is a good example of mid-century International style in a public building.

The 1950s decade witnessed new modern style religious buildings. The Central Bible Church (1953) evolved from a merger of Central Bible and the West Side Norwegian Methodist Church. Harry Schmautz was the architect.

That same year, the Lutheran church added a new wing for its youth ministry, the Hjortland Memorial, which is one of Kalispell’s most impressive 1950s design. Ray Thone was the architect.

In 1958 Central Christian Church completely remodeled its earlier 1908 building to a striking modern design.

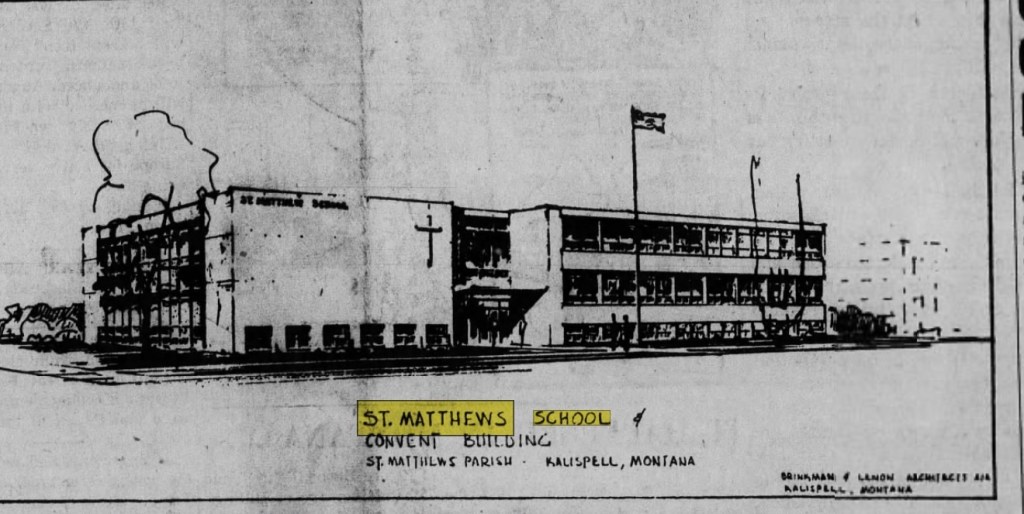

That same year came the opening of St. Matthew Catholic School, an impressive two-story example of International style in an institutional building. the architect was the firm of Brinkman and Lenon.

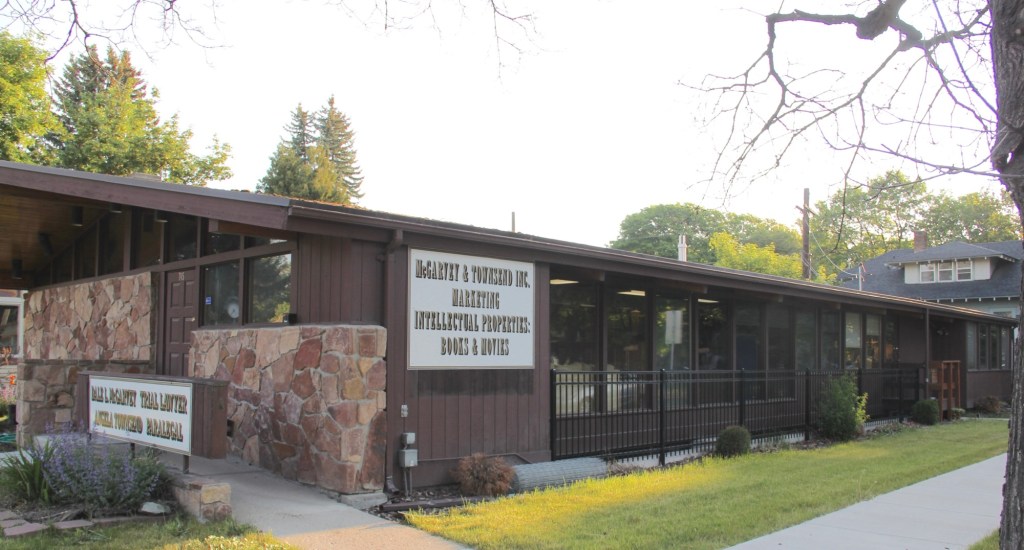

Kalispell also has two excellent examples of commercial buildings in the mid-century contemporary style. Below is the stone veneer and window wall of the McGarvey and Townsend building.

But my favorite, until a recent “remuddling,” is the Sutherland Dry Cleaners, now a golf supply shop.

Kalispell has several good examples of mid-century domestic design. My favorite is this Ranch-style residence near the Conrad Mandion.

This post doesn’t include all of Kalispell’s modernist designs but hopefully I have included enough to demonstrate that the town has a significant modernist architecture tradition.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings. The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

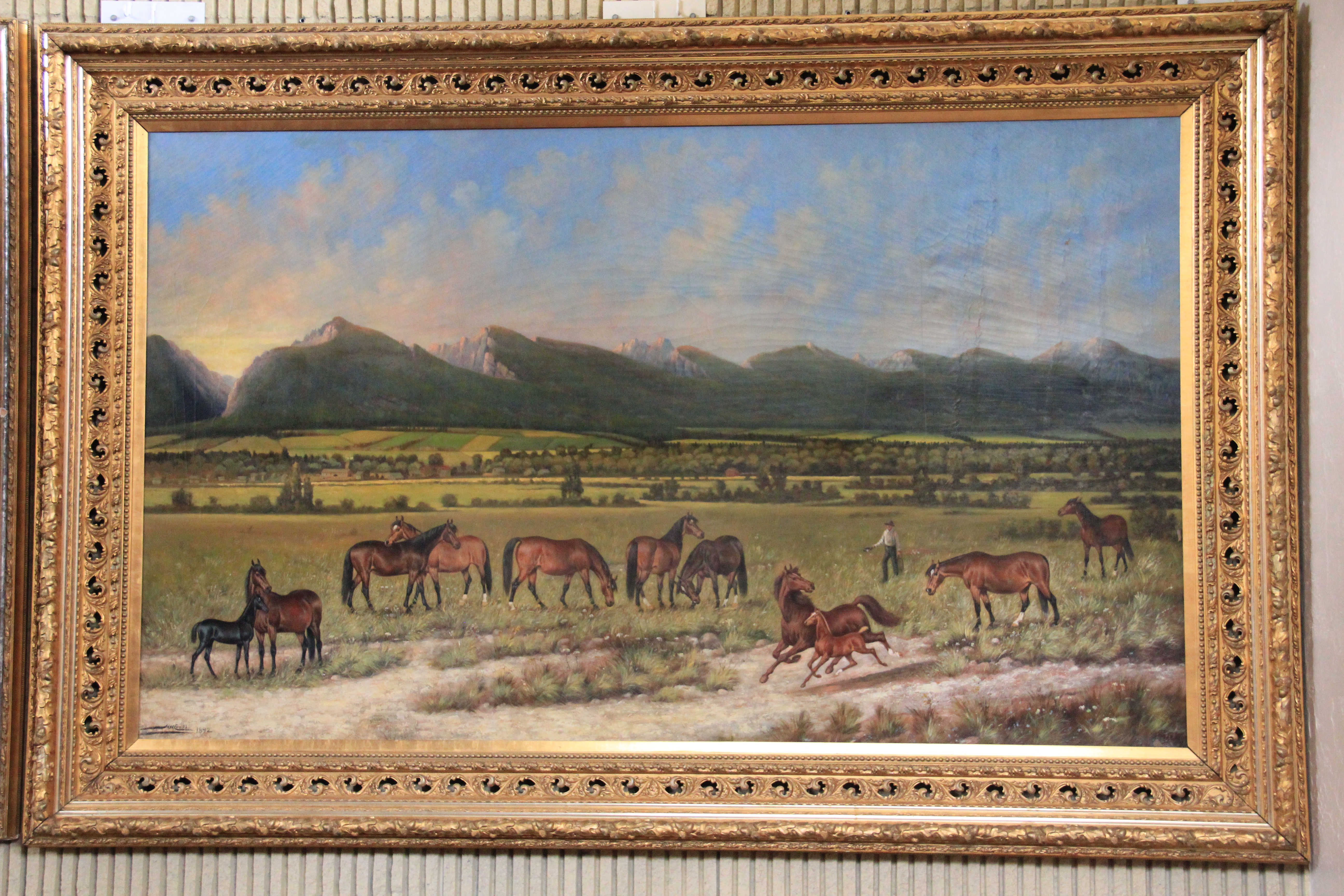

Marcus Daly, the copper magnate of Butte and Anaconda, certainly put his stamp on the landscape of Silver Bow and Deer Lodge counties. But not until the early 1980s did most Montanans understand that Daly too had shaped the landscape of the Bitterroot Valley with the creation and expansion of his Bitterroot Stock Farm, starting in 1886 and continuing even beyond his death in 1900.

Marcus Daly, the copper magnate of Butte and Anaconda, certainly put his stamp on the landscape of Silver Bow and Deer Lodge counties. But not until the early 1980s did most Montanans understand that Daly too had shaped the landscape of the Bitterroot Valley with the creation and expansion of his Bitterroot Stock Farm, starting in 1886 and continuing even beyond his death in 1900.

to have a place, on the other side of the divide from his dark, dank, smelly mining towns, where he and his family could escape and enjoy Montana’s open lands and skies. The ranch began with the purchase of the Chaffin family homestead in 1886. Daly immediately set forth to remodel and expand the older ranchhouse yet those changes only lasted three years when Daly replaced the first house with a rather grand and flamboyant Queen Anne-styled mansion and named it Riverside. Daly died in 1900 and Riverside’s last grand remodeling was guided by his wife, who looked to architect A. J. Gibson of Missoula to design a Colonial Revival-on-steroids mansion, which referenced the recent Roosevelt family mansion on the Hudson River in New York State.

to have a place, on the other side of the divide from his dark, dank, smelly mining towns, where he and his family could escape and enjoy Montana’s open lands and skies. The ranch began with the purchase of the Chaffin family homestead in 1886. Daly immediately set forth to remodel and expand the older ranchhouse yet those changes only lasted three years when Daly replaced the first house with a rather grand and flamboyant Queen Anne-styled mansion and named it Riverside. Daly died in 1900 and Riverside’s last grand remodeling was guided by his wife, who looked to architect A. J. Gibson of Missoula to design a Colonial Revival-on-steroids mansion, which referenced the recent Roosevelt family mansion on the Hudson River in New York State.

There is really nothing in the world of domestic architecture in Montana to compare to the Daly family’s Riverside estate. As we made our plans for the state historic preservation survey in 1984, I never imagined gaining access to this mysterious place. Then, suddenly, the owners decided to offer the property to someone–the state preferably but locals if necessary–who could transform it into a historic house museum and still working farm.

There is really nothing in the world of domestic architecture in Montana to compare to the Daly family’s Riverside estate. As we made our plans for the state historic preservation survey in 1984, I never imagined gaining access to this mysterious place. Then, suddenly, the owners decided to offer the property to someone–the state preferably but locals if necessary–who could transform it into a historic house museum and still working farm.

Indeed not far away is a 21st century sign of the super-rich and their imprint on the Montana landscape: the Stock Farm Club, a private, gated community for those who can afford it–and probably 99% cannot.

Indeed not far away is a 21st century sign of the super-rich and their imprint on the Montana landscape: the Stock Farm Club, a private, gated community for those who can afford it–and probably 99% cannot.