While working along the Hi-Line in 1984, I encountered the motto, “Havre Has It” seemingly everywhere. While the slogan was corny, it was true I kept on thinking in that Havre had the best shopping, the better restaurants (here’s to the old Duck Inn), the best collection of historic architecture, the university of the region, etc.

Although I didn’t realize appreciate it in 1984, it is quite apparent in the 21st century that Havre also has the region’s best collection of modernist designs. In the new issue of Montana: The Magazine of Western History, H. Rafael Chacon has a wonderful article on “Montana Modernism.” It is highly recommended reading as one of the best articles on Montana architecture published in the magazine over the last two decades. Chacon highlights MSU-Havre’s Armory Gymnasium, designed by Montana architect Oswald Berg. He includes photos of the building under construction and then as the finished building.

The 1950s saw many universities receiving federal dollars to construct large campus buildings that served both as new gymnasiums and growth in popularity in college basketball but also as offices for ROTC and similar military programs. In 2008 I documented a similar dual-purpose building at the University of Tennessee, also built in the late 1950s. The UT Armory-Gymnasium building is also modernist in design, but subdued in its presentation compared to the Northern Montana College gym, with its bit of influence from Saarinen’s very famous 1955 modernist design of the Kresge Auditorium at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Although lacking the splash and dash of the Kresge Auditorium, these views of the end elevations of the Northern Montana College gym clearly show the influence of Saarinen’s earlier design.

Havre’s traditions of modernism are not merely an aesthetic introduced form the outside by state government. In the residential historic district there is an Art Deco/International style building that embodies 1930s style.

Then, more importantly, there is the Havre Central High School and Gym of 1949-1951 that reflects the New Deal interpretation of modernist ideals of the 1930s as embodied in literally hundreds of similarly styled schools funded by the Public Works Administration and the Works Progress Administration across the country.

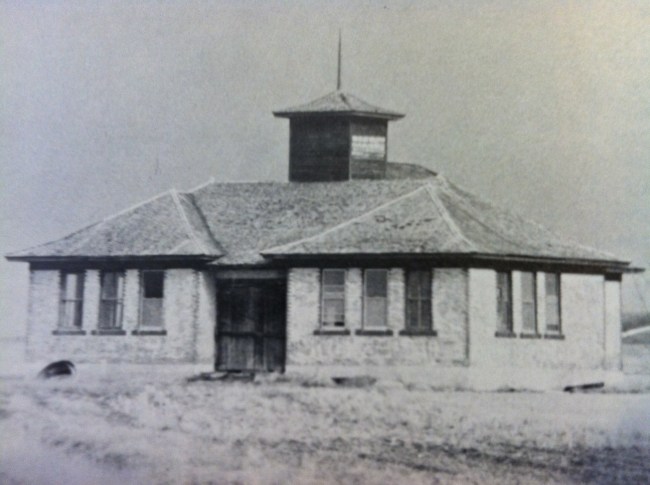

The new design of the school stood in stark contrast to the city’s public building aesthetic of the first half of the 20th century, best represented by the Classical Revival style of the Hill County Courthouse and the monumental Colonial Revival of the U.S. Post Office and Federal Building.

Then, two years after the high school and gym were finished came the remodeling and expansion of the Great Northern depot in 1953. Suddenly there has a long rectangular block of brown/gold bricks in the center of town, a structure totally at odds with the earlier tradition of slightly Victorian-styled or Classical influenced passenger stations that served as literal gateways to the railroad towns of the plains.

Can anyone doubt the influence of the Great Northern on the prospects and identity of Havre in the 1950s? It was the key economic engine. In the wake of the new passenger station, other businesses and institutions in downtown Havre shed their earlier skins for the look of modernism. The Bell Telephone building was a sharp-edged box, influenced by an International style look of shifting patterns of brick and glass.

Adding significantly to the city’s rich legacy of church architecture is the 1959 almost Prairie -style achievement of the Van Orsdel Methodist Church, located on the edge of the town’s residential historic district.

The Schafer Insurance Services building–a striking commercial example of what was called contemporary design (think of the angles and sweep of the modern house featured in the classic Hitchcock film, North by Northwest)–sits square in the town’s residential historic district.

The city pool, across from the high school, exhibited another version of contemporary design, tending in fact toward what architectural historians call “Ranch style,” similar to many new suburban homes being built in Havre in the 1950s and 1960s.

And the impact of modernism was not over at Northern Montana College. The rambling, Ranch-style effect of Morgan Hall and the more Miesian Student Union Center, combined with the gym and the earlier mechanical arts building to turn what had been a typically Gothic Revival campus of the turn of the century into an almost hip, “with it” college environment of the 1960s.

The epitome of Havre’s new look came in the early 1970s with the decision to build a new hospital. The Northern Montana Hospital (1975) is an impressive achievement, almost as if a spaceship had landed on the town’s northern outskirts. If it had been built a few years earlier, pundits no doubt would have called it “star wars” style. More fairly, the building expresses our faith in modern medicine, and complements well the modernist style of the adjacent Northern Montanq College campus. Certainly Northern Montana College represents the capstone of a generation of change within Havre, which can be explored today by discovering the town’s modern architecture landmarks.