One of my favorite, if not #1 itself, Depression-era buildings in Montana is the amazing Federal building in Glasgow. First, this triumph of New Deal design from 1939 is a powerful statement in the public architecture of northeast Montana.

As you may know, Glasgow embraces its reputation as the most isolated place in the nation, that it is the definition of the middle of nowhere (a reputation however that I really challenge). But the restrained classicism of the building is refined and tasteful, perfect of the region.

Second, I really admire the building because it is so intact after 86 years of use. Yes, there are some alterations, but when you step into the post office lobby, you do feel like you stepped back in the 1930s.

Then there is the wonderful mural, “Montana’s Progress,” by Forest Hill. Completed in 1942, as the county’s other major, and huge, New Deal project, Fort Peck Dam and powerhouse, was gearing up to maximum production for World War II.

The left side speaks to the Native American past and the nearby presence of Fort Peck Reservation. There’s even a reference to gold panning, which never happened along this section of the Missouri. Then the right side reference the coming of settlers and the parceling of once open land into regular measured surveys.

The center section speaks to the Progress, predicted to come, centered on railroads, agriculture (cattle, wheat, hay, sheep), and industry, with the commanding image of the amazing Fort Peck spillway ( already world famous to an earlier feature story in Life magazine) and in the top corner, a sugar beet refinery.

The bomber flying above it all of course spoke to the immediate present , of World War II, but it also correctly predicted the future. The town and county would have its greatest period of prosperity in the 1950s and 1960s with the Glasgow Air Force Base.

What a historic document of its time and what an amazing building, still serving the community almost 90 years later.

Dillon is not a large county seat but here you find public buildings from the first third of the 20th century that document the town’s past aspirations to grow into a large, prosperous western city. It is a pattern found in several Montana towns–impressive public buildings designed to prove to outsiders, and perhaps mostly to themselves, that a new town out in the wilds of Montana could evolve into a prosperous, settled place like those county seats of government back east.

Dillon is not a large county seat but here you find public buildings from the first third of the 20th century that document the town’s past aspirations to grow into a large, prosperous western city. It is a pattern found in several Montana towns–impressive public buildings designed to prove to outsiders, and perhaps mostly to themselves, that a new town out in the wilds of Montana could evolve into a prosperous, settled place like those county seats of government back east.

The Dillon City Hall also belongs to those turn-of-the-20th century public landmarks but it is a bit more of a blending of Victorian and Classical styling for a multi-purpose building that was city hall, police headquarters, and the fire station all rolled into one.

The Dillon City Hall also belongs to those turn-of-the-20th century public landmarks but it is a bit more of a blending of Victorian and Classical styling for a multi-purpose building that was city hall, police headquarters, and the fire station all rolled into one.

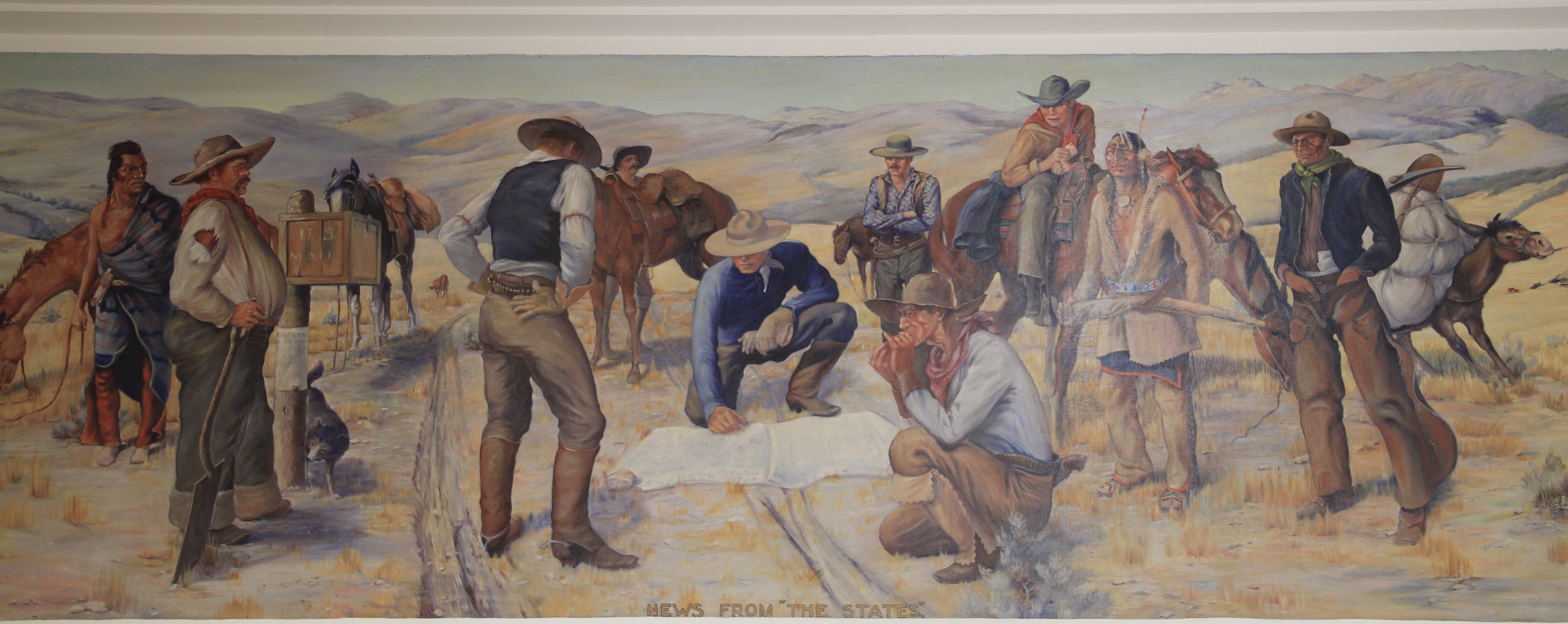

A New Deal era post office introduced a restrained version of Colonial Revival style to Dillon’s downtown. The central entrance gave no hint to the marvel inside, one of the

A New Deal era post office introduced a restrained version of Colonial Revival style to Dillon’s downtown. The central entrance gave no hint to the marvel inside, one of the

state’s six post office murals, commissioned and executed between 1937 and 1942. The Dillon work is titled “News from the States” painted by Elizabeth Lochrie in 1938. It is a rarity among the murals executed across the country in those years because it directly addressed the mail and communication in early Beaverhead County. Ironically, few of the post office murals actually took the mail as a central theme.

state’s six post office murals, commissioned and executed between 1937 and 1942. The Dillon work is titled “News from the States” painted by Elizabeth Lochrie in 1938. It is a rarity among the murals executed across the country in those years because it directly addressed the mail and communication in early Beaverhead County. Ironically, few of the post office murals actually took the mail as a central theme. The New Deal also introduced a public modernism to Dillon through the Art Deco styling of the Beaverhead County High School, a building still in use today as the county high school.

The New Deal also introduced a public modernism to Dillon through the Art Deco styling of the Beaverhead County High School, a building still in use today as the county high school.

A generation later, modernism again was the theme for the Dillon Middle School and Elementary school–with the low one-story profile suggestive of the contemporary style then the rage for both public and commercial buildings in the 1950s-60s, into the 1970s.

A generation later, modernism again was the theme for the Dillon Middle School and Elementary school–with the low one-story profile suggestive of the contemporary style then the rage for both public and commercial buildings in the 1950s-60s, into the 1970s.

The contemporary style also made its mark on other public buildings, from the mid-century county office building to the much more recent neo-Rustic style of the Beaverhead National Forest headquarters.

The contemporary style also made its mark on other public buildings, from the mid-century county office building to the much more recent neo-Rustic style of the Beaverhead National Forest headquarters.