Recently there has been much needed discussion in the historic preservation field on the necessity of focusing of the many types of citizens and residents who created and sustained our historic landscape. Don’t be so building focused; think about place. Nestled behind an attractive public playground on Main Street, not far from the ultra-modern Bozeman Public Library, is such a place: Sunset Hills Cemetery. It is an absolutely compelling place to walk along its many rows and curvilinear driveways to find the stories of Bozeman, written in stone, concrete, and metal.

Within the cemetery is one of the oldest physical remnants from the city’s beginning: the marker for Lady Mary Blackmore, July 1872, when Bozeman was nothing more than a string of tents, log cabins, and false front buildings along the Bozeman Trail.

The metal plaque on the slowly decaying pyramid marker tells part of the story. Lord William Blackmore and Lady Mary Blackmore had a deep interest in the west and they came to visit newly designated Yellowstone National Park in 1872. Mary took ill and did not make the trip to the park. After her health markedly declined, citizens went to find Lord Blackmore and he returned, but Mary never recovered. Blackmore to honor his wife, and to acknowledge the support and kindness of local residents, purchased 5 acres for a public cemetery and had the pyramid marker installed. Today this oldest section of the cemetery is on the west side, The view from the Blackmore marker is impressive.

The Daughters of the American Revolution in 2020 addressed other early burials in the cemetery through this obelisk marker in memory of those without grave markers today.

Nearby is the very different grave marker for another important early settler and rancher, Nelson Story. Whereas the Blackmore marker is direct, dignified, the Story marker is designed to remind everyone that here lies an important person.

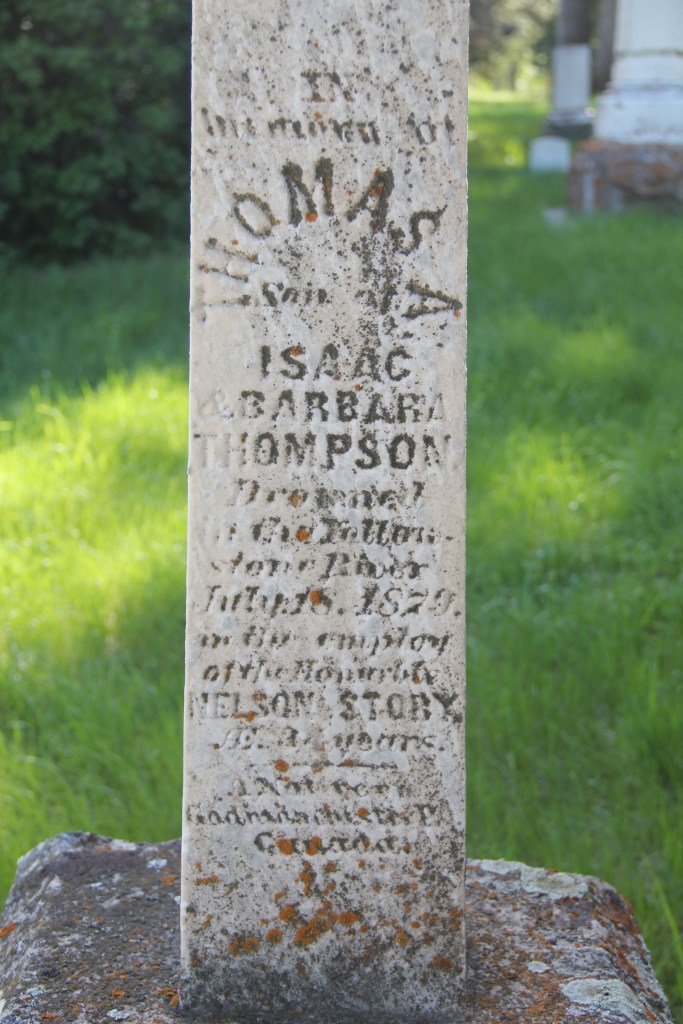

You walk through an overpowering classical-staled gateway to find the graves of Story and his family. And his employees. The marker for Tom Thompson (d. 1879), the son of Isaac and Barbara, tells the story of a young man who drowned in the Yellowstone River while “in the employ of the Honorable NELSON STORY.”

But Thompson’s story if far from the only one shared in Sunset Hills Cemetery. There are many gravestones that bear the emblems of fraternal organizations, some well known, some not so much.

Sunset Hills Cemetery has a dedicated veterans section at the rear of the property that is centered around a 1928 Grand Army of the Republic (GAR) monument to those who served in the U.S. and Union Armies during the Civil War. It is unique because typically the GAR monuments date to the decades right after the war, or perhaps up to 1915, which was the 50th anniversary of the end of the Civil War.

Scattered throughout the cemetery are the simple standardized gravemarkers that the federal government provided to families of U.S. veterans. This place is another reminder of the impact of the Civil War on late 19th century America.

Almost all historic cemeteries in Montana have sections for veterans and special markers designate fraternal lodge membership and prominent citizens. Sunset Hills Cemetery has all of that over its 150 years of existence–and more. Whatever row of graves you choose to explore you will find markers of beauty, of memory, and sadness.

I have explored many municipal cemeteries in Montana–but did not venture into this special place until 2021. Don’t repeat my mistake–here is a place worth exploring, just set aside plenty of time to do. It is not in the National Register of Historic Places–but it should be.

These images speak to the cemetery’s architectural significance, another point of emphasis for a National Register nomination. The cemetery has several elaborate grave markers, a virtual sculpture garden that also speaks to the city’s artistic expressions.

These images speak to the cemetery’s architectural significance, another point of emphasis for a National Register nomination. The cemetery has several elaborate grave markers, a virtual sculpture garden that also speaks to the city’s artistic expressions.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples.

To wrap up this multi-post look at Missoula and Missoula County, let’s take a brief look at the city’s historic neighborhoods. With seven historic districts, Missoula is rich in domestic architecture, and not only the homes built during its rise and boom from the early 1880s to the 1920s–there also are strong architectural traditions from the post-World War II era. This post, however, will focus on the early period, using the South Side and East Pine historic districts as examples. Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings.

Listed in the National Register of Historic Places 25 years ago, the south side district was platted in 1890, with development especially booming after the turn of the century and the arrival of the Milwaukee Road depot by 1910. Within that 20 year period, an impressive grouping of domestic architecture, shaped by such leading architects as A. J. Gibson, was constructed, and much of it remains today. When the state historic preservation office designated the district in 1991, there were over 200 contributing buildings. The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

The neighborhood contains some of the city’s best examples of Queen Anne style, as seen above but also has many different examples of other popular domestic styles of the era, such as the American Four-square and variations on the various commonplace turn of the century types as the bungalow.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Apartment blocks and duplexes from the turn of the century also are important contributing buildings to the neighborhood. They reflect the demand for housing in a rapidly growing early 20th century western city.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

Before we leave Missoula, I want to also briefly consider its historic 1884 cemetery, an often forgotten place as it is located on the northside of the Northern Pacific Railroad corridor, and a property, like so many in 1984-1985, I gave no consideration to as I carried out the fieldwork for the state historic preservation plan.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.

A large concrete cross and adjacent river rock stone lined marker pay homage to the cemetery’s earliest burials as well as the many first citizens interred here.