Riverside Cemetery dates to 1883, a time of considerable change and expansion in Fort Benton’s history. Just 2 years earlier, summer 1881, the U.S. Army left the fort, and it began a rapid decline. In the following winter of 1881-1882 the town began a building boom that led to the construction of the Grand Union Hotel by the end of 1882.

Freight traffic on the Missouri River also boomed and the River Press, the city’s leading newspaper for the next 100 plus years, published its first edition. 1882 also witnessed the city’s first electric lights and the construction of many new residences. And by the year resident had formed the Riverside Cemetery Association.

The loss of the Chouteau County Courthouse to fire in early 1883 didn’t seem to slow momentum at all. That spring voters incorporated Fort Benton—what had been a trading and military town was now a formally established town. Soon thereafter Riverside Cemetery was established on the Missouri River bluffs northeast of town.

The new town cemetery had approximately 40 fenced acres and was ready for use by Decoration Day (now known as Memorial Day) in 1883. The cemetery also had reinterred graves from earlier in-town cemeteries at approximately the location of First Christian Church and behind Haas and Associates and Farmers Union Oil Company.

Today the gap between the initial cemetery and burials in the 20th century is noticeable. The early burials are on the east side while the modern section is on the east side clustered near a row of trees m. Clearly early tombstones have been lost—the number of grave depressions indicate that there are many additional burials that lack a grave marker.

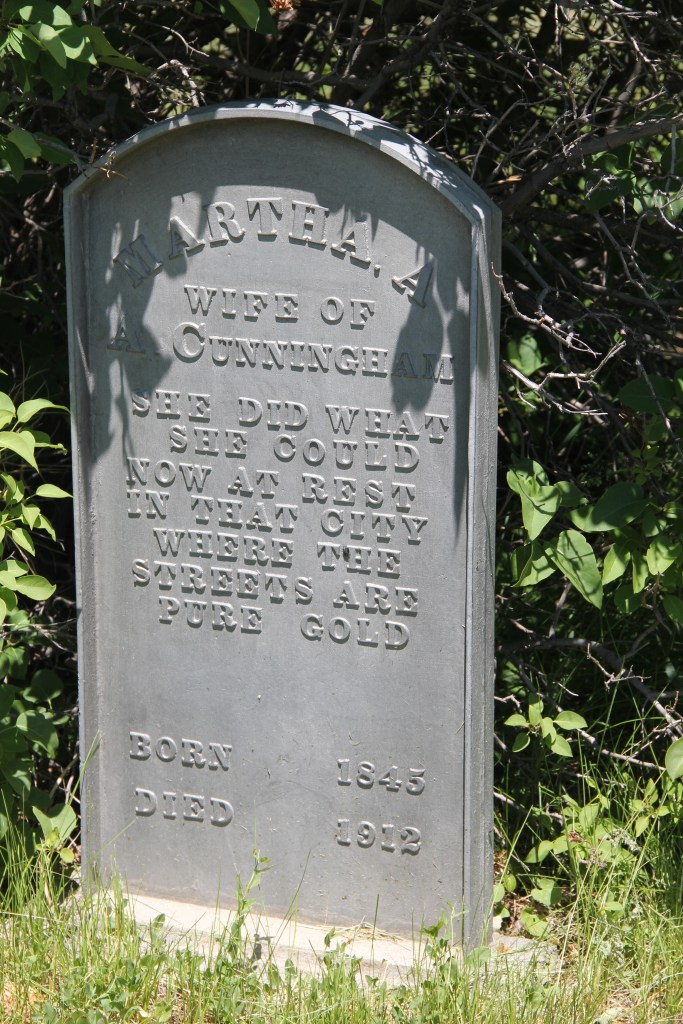

The remaining grave markers from the late 19th century tell powerful stories. The Charles Fish (d. 1890) obelisk with urn marker below honored a Canadian native who served as a drummer boy with the 38th Wisconsin Infantry in the Civil War; he was only 15 years old when he joined.

Tombstones with cross themes mark the graves of Jane Jackson (d. 1885) and Edward Kelly (d. 1890).

In 1891 the cemetery received its first U.S. military veterans markers. The one below was for Patrik (the spelling used on the tombstone) Fallon, a Civil War veteran. By now Fort Benton had grown to the point that its Decoration Day ceremony involved hundreds, led by the cemetery association, camps of the Grand Army of the Republic and soldiers from Fort Assiniboine.

While the graves of many pioneers are unmarked, the Sullivan family located its graves near the edge of the bluff, truly an awe-inspiring setting overlooking the town, river, and railroad tracks.

Impressive tombstone art is scattered throughout the cemetery. The unique yet beautiful pressed metal crosses for brothers Julius (d. 1923) and Henry (d. 1924) Bogner belong, stylistically to the Victorian era, but were commissioned and installed in the Jazz Age.

Riverside Cemetery has an impressive veterans section, known as the Military Plot. Veterans from the Spanish American War of the 1890s to the conflicts of the 21st century are buried here.