Established in 1963, Butte’s World Museum of Mining is both a historic site and a historic building zoo. It preserves and interprets the Orphan Girl Mine while it also re-creates a fanciful Hell Roarin’ Gulch, with the townscape filled with both moved historic buildings and modern interpretations of the mining camp that existed in Butte in the late 19th century.

The Orphan Mine historic site is the best single place in Montana to explore the gritty reality of deep-shaft mining in the Treasure State.

The metal cages that the mines used to go down into the mines still give me the chills–the sacrifices these men made for their families and community is impressive.

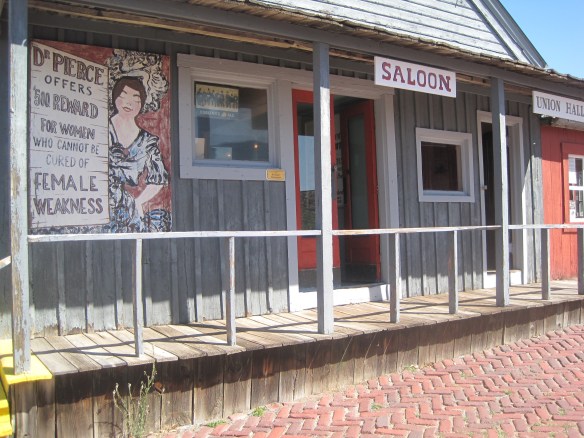

The Hell Roaring’ Gulch part of the museum is in stark contrast to the mid-20th century engineered, technological landscape of the Orphan Girl Mine. It interprets the mining camp days of Butte from the late 1860s into the 1880s before the corporations stepped in and reshaped the totality of the copper mining industry and built environment of Butte.

The Hell Roaring’ Gulch part of the museum is in stark contrast to the mid-20th century engineered, technological landscape of the Orphan Girl Mine. It interprets the mining camp days of Butte from the late 1860s into the 1880s before the corporations stepped in and reshaped the totality of the copper mining industry and built environment of Butte.

Like many building zoos of the highway era (the museum is easily accessed from the interstate), the recreated town emphasizes the ethnic diversity of the mining camp as well as some of the stereotypes of the era.

But the exhibit buildings also have several strong points, especially in their collections, such as the “union hall” (you do worry about the long-term conservation of the valuable

artifacts and banners shown in this photo); the store, which displays common items sought by the miners and their families; and various offices that show the business of

artifacts and banners shown in this photo); the store, which displays common items sought by the miners and their families; and various offices that show the business of

mapping the mines, registering claims, and assaying the metals .

mapping the mines, registering claims, and assaying the metals .

In my first post about the World Museum of Mining, I addressed this valuable collection of a historic mine, several historic buildings, and thousands of historic artifacts briefly. Properties like the impressive log construction of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shown below, are invaluable. The World Museum of Mining deserved more attention, and it deserves the attention of any serious heritage tourist to Montana.

In my first post about the World Museum of Mining, I addressed this valuable collection of a historic mine, several historic buildings, and thousands of historic artifacts briefly. Properties like the impressive log construction of St. Patrick’s Catholic Church, shown below, are invaluable. The World Museum of Mining deserved more attention, and it deserves the attention of any serious heritage tourist to Montana.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today.

In restoring Virginia City, the Bovey family thus worked within a local government context. The Montana Heritage Foundation also works within that context today. There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

There was no living community here to speak of. It presented the opportunity for the Boveys to acquire and save other buildings from the area, however. The Finney property became the historic foundation of one of the state’s first “building zoos”–a collection of historic buildings moved together to tell a local history story. In 1984, when I was surveying Montana for the state historic preservation plan process, I paid little to no attention to Nevada City–here, I thought, was fake western history, with a bunch of moved buildings, which by definition are rarely eligible for the National Register.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Nevada City tells multiple stories. One of the most apparent is how heritage tourism has shaped the late 20th century historic preservation movement. The lodging and restaurant at Nevada City is part of the general sustainability plan for the entire operation. The authentic environment and ease of highway access are major draws for tourists.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

Another way to consider Nevada City is how heritage tourism ideas of the 1960s–especially the idea of excursion passenger trains–impacted the built environment. What is now known as Alder Gulch Railroad started c. 1964, a way of attracting visitors to stop in Nevada City where then they could take the short ride to Virginia City.

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.

telling example of how historic preservation worked in the West, a true public-private partnership, in the years immediately before the passage of the National Historic Preservation Act in 1966.