Like hundreds of others who crowded into the new wing of the Montana Historical Society to get a sneak peek of the new state history exhibit, titled Montana Homeland, I expected to be dazzled. After all it had been 40 years since MHS had last updated its primary history exhibit.

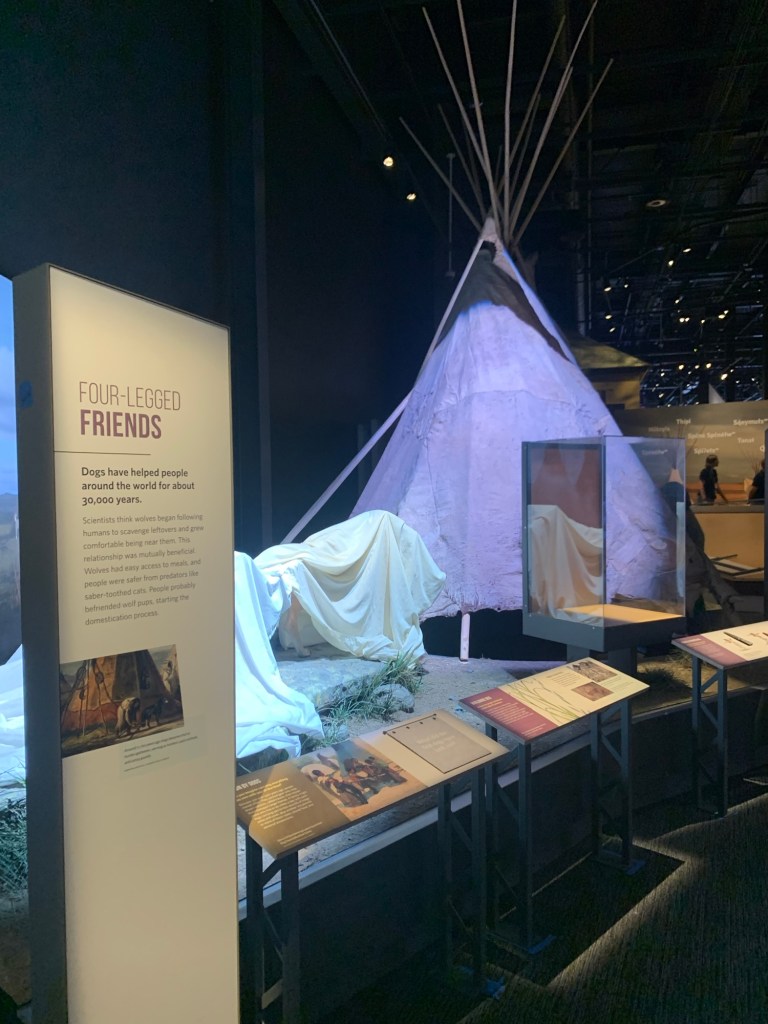

The architects gave the exhibit designers a huge lofty space and there are tipis galore, their height dominating everything around them, challenged only by a reproduction headframe.

The headframe is in a corner and fades into the background unlike the tips which literally command most views within the exhibit, even at the end.

The message of the exhibit team is not subtle—Indigenous people dominate the past of the lands that today comprise Montana—but the hand of people in the last 100 years also dominate the built environment. The exhibit is missing the one lofty structure that is still found everywhere, representing a property type that also ties together so much of the state’s history—the Grain Elevator. Wish there was one in these lofty spaces. It helps to explain the impact of agriculture, the homesteading era, railroad lines, and town creation.

20th century Montana is thus far greatly underrepresented in the exhibit, almost as if the attitude was that nothing matters that much after the homesteaders—let’s wrap this baby up!

But by so doing you downplay the huge impact of the engineered landscape on the homeland, especially the federal irrigation programs that produced mammoth structures that reoriented entire places—Gibson Dam comes right to mind, and then there’s Fort Peck.

Irrigation also is central because of the diversity of peoples who came in the wake of the canals and ditches. Not just the Indigenous, not just the miners but the farmers and ranchers added to the Montana mosaic. A working headgate—would that help propel the story?

Right now the answer is no. There are many, many words in this exhibit, and, as people seem to want to do nowadays, the words are often preachy. I wondered about the so 2020s final section, where visitors are implored to live better together by accepting diverse peoples.

Montana is nothing but a melding of diverse peoples, from 14 tribes, the 17-18 ethic groups at Butte, the Danes of the northeast, the Finns of the Clark’s fork, and the Mennonites of the central plains, etc etc. if they had started challenging character of the actual Montana landscape had been front and center, then let history unfold to show how many people of all sorts of origins and motives tried to carve a life from it—you would have a different exhibit and one not so preachy.

Let’s hope the Final Cut has many less words, many more objects and a greater embrace of the state’s 20th century transformations.